Immigration detention as an exceptional measure of last resort

Since the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the right to personal liberty has been taken up in various international treaties. This right is one of the main frameworks for addressing the arbitrary detention of people on the move.

As part of migration management, governments around the world carry out various actions as part of state policy, one of which is detention.

IDC has documented the various detrimental effects of immigration detention, including the criminalisation of migrants (including those in need of international protection), psychosocial effects on individuals and their communities, human rights violations, as well as high costs to governments.

"Irregular migration is not a choice of the people, but a consequence of the policies and actions of the state.”

Therefore, international standards support the elimination of immigration detention, and one of the strategies to achieve this is to limit its application only as an exceptional measure of last resort. This principle has been taken up in various countries and is enshrined in their legal frameworks; however, there are several challenges in its implementation.

How can the principle of last resort for immigration detention be applied?

In order to ensure that states gradually eliminate and put a complete end to the use of immigration detention, there are some key advocacy actions that can be taken up by legislative actors, public officials or civil society organisations themselves.

Several international instruments prohibit immigration detention for various groups, such as children and adolescents, asylum seekers or people in vulnerable situations, such as pregnant women, nursing mothers, elderly people, people with disabilities, LGBTQI people, or survivors of human trafficking, torture and other serious violent crimes.

In the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, States have committed to prioritise non-custodial alternatives consistent with international law, and to adopt a human rights-based approach to any detention of migrants, where detention is only used as a last resort.

The exceptionality of detention must be based on an individual and context-specific assessment, an analysis of all options, and the decision to opt for detention must be lawful and demonstrate a legitimate aim.

Based on the experiences of its members and partners, IDC set out to compile promising practices in the application of the principle of last resort around the world, including examples of national legislation and its possible effect on the use of detention as an immigration control measure.

Find out more:

We invite you to read our briefing paper – Immigration Detention as an Exceptional Measure of Last Resort – to learn more about the international standards in which the principle of last resort is raised, as well as some promising practices, in order to encourage further progress on this issue.

Strengthening Capacity to Protect & Promote the Development of Migrant Children in the Americas

As the movement of people from one territory to another becomes increasingly more frequent, the ways in which this happens has transformed. In the recent past, groups were generally small and were transported as inconspicuously as possible. Most of the group would comprise of men, and economic-labor motivations lay behind most migration.

Current migration dynamics are more diverse: expulsion factors have increased and intensified; groups gather in caravans and travel on main highways to border points; traditionally male migration has gradually decreased with an increase of migrant women; and there has been an alarming increase in the number of children crossing borders, either accompanied, unaccompanied, or separated from their parents or legal guardians.

Such a context demands that the State, and the various actors that comprise it, develop mechanisms for the specific attention and protection of all those immersed in voluntary or forced processes of migration. Special emphasis needs to be placed on the most vulnerable, such as children, founded on the “best interest” principles of this population.

According to the Committee for the Rights of Children,[1] the best interest of the child is a right, a principle, and rule of procedure. It demands the adoption of a rights-based approach, in which all parties seek to guarantee the physical, psychological, moral, and spiritual integrity of children and to promote their human dignity, encompassing in the term “children,” both an individual and general or group character. “Best interest” of the child is thus understood as both a collective and an individual right.

The Committee has also referred to how the best interest of the child should be applied, arguing that pre-evaluations of legislative provisions, public policies, and their implementation, should be conducted in order to assess their potential effects on the rights of children, together with a post-evaluation of the consequences of their application.[2]

Considering the context of migration, as well as international doctrine and regulations, the need to support and strengthen the capacity of the various regional institutions involved in attention and protection of migrant children has been identified. This would enable the implementation of effective approaches that respond to both the humanitarian needs of this population as well as to intentional design of life projects, all founded on the best interest of the child.

In order to support the development and strengthening of the technical abilities of personnel from the above mentioned institutions, and within the framework of the 26th Regional Conference on Migration (RCM), a Diploma on Migrant Children was offered. The Diploma was designed to strengthen the technical capacity of those working in institutions that participate in processes of migrant children, in order to protect this population.

The Diploma design was based on a proposal by Grupo de Monitoreo Independiente de El Salvador (GMIES), and was reinforced by a participative and consultative process with the International Organisation for Migration, International Detention Coalition (IDC), the International Labor Organisation, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, as well as by the representation of the Pro-Tempore Presidency (PPT) and the Regional Conference on Migration. Together, this allowed for a holistic, specialised, and consensual vision of the different bodies that, from their own particular position, address one or more aspects of human migration.

The Diploma was delivered to 41 participants from public institutions and non-governmental organisations from 10 countries in the Mesoamerican region. On completion of their training, each participant received a certificate from the "Doctor José Gustavo Guerrero" Specialised Institute. This Institute provided a perfect space on their platform for the transmission and reinforcement of knowledge, including simultaneous classes for consultation and feedback; pre-recorded classes that could be watched at participants’ convenience, and forums to respond to any questions.

The Diploma was divided into three modules, progressing from a general to a specific perspective, with information on the provision of immediate attention, as well as on accompaniment and orientation for life projects that ensure a decent standard of living. A brief summary of the contents of each module is presented below:

| MODULE I.

UNDERSTANDING THE REALITY OF MIGRANT CHILDREN |

Exploration of the regional context and reality of migrant children, with particular emphasis on the structural causes of countries of origin that give rise to migration, as well as the characteristics of migrant children.

Analysis of situations of vulnerability. Examination of risk situations, such as human trafficking, trafficking of migrants, discrimination based on indigenous identity, belonging to the LGBTTTIQA+ community, migrant detention, gender based sexual violence, among others. Provision of tools to identify vulnerabilities, with particular emphasis on interview techniques. |

| MODULE II.

MIGRANT CHILD PROTECTION

|

Examination of the international and regional legal framework as well as of standards for the protection of the rights of migrant children; minimum regulations for protection, asylum and statelessness, child labor.

Strengthening the technical capacity of comprehensive mechanisms for the assistance and protection of migrant children: application of best interest, humanitarian action, mental health, and alternative care for unaccompanied and separated children. |

| MODULE III.

IDEAL ECOSYSTEMS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF MIGRANT CHILDREN’S LIFE PROJECTS

|

Presentation of mechanisms for reintegration in countries of origin for returned migrant children, as well as mechanisms for integration in destination countries, considering the various migration dynamics and their possible effects on migrant children

Exchange of good practices for the protection and development of migrant children, and examination of state and civil society responses to the current reality. |

The Diploma ended on 13 October 2022.

[1] United Nations Organization, Committee for the Rights of Children, General observation Nº 14 (2013) on the rights of the child to have their best interests taken as a primary consideration (article 3, paragraph 1). Approved by the Committee in its 62nd session, held from January 14 to February 1, 2013.

[2] Op. Cit.

Written by Pamela Anthuanee Franco, Grupo de Monitoreo Independiente de El Salvador (GMIES)

Exchange of Promising Practices for the Implementation of the Migrant Child Protection Protocol in 3 Mexican States

In August 2022, International Detention Coalition, Asylum Access Mexico, Kids in Need of Defense (KIND), and the Institute for Women in Migration (IMUMI) hosted child protection authorities, migrant children, international agencies, and civil society organisations at an event in Mexico City aimed at reflecting on and exchanging ideas. Specifically, the event provided the opportunity to share successes and challenges in the implementation of the Migrant Child Protection Protocol,[1] as well as of laws that prohibit the detention of migrant children in the states of Veracruz, Tabasco, Chiapas, and Mexico City. It aimed to create a space for the exchange of promising practices and work experiences.

IDC and the other convening organisations have been working with the protection authorities of Veracruz, Tabasco, and Chiapas, as well as with civil society organisations, and public and private Centres for Social Aid in these states since 2021, in order to contribute to the implementation of laws that prohibit the detention of migrant children and to the adaptation of the Migrant Child Protection Protocol on a state level. Among other actions, we have attended directly to cases, strengthened the capacity of shelters and child protection authorities, and provided technical support for local protection systems to form protection commissions that adapt and implement the Migrant Child Protection Protocol on a local level.

Participants in the event shared their knowledge and experience on a variety of issues during two panel sessions and three working group sessions. Issues covered included the local implementation of the Child Protection Commission, or Working Groups, as well as practical tools for the protection of children, and Alternative Care Models.

In seeking to create a space for protection authorities and state Protection Systems to meet, discuss actions undertaken for the protection of migrant children, and build agreements for collaborative work, the following results were achieved:

- Progress in articulating municipal-state-federal level authorities to coordinate the attention to and protection of migrant children, including establishing dialogue and coordination mechanisms.

- Recognition of the technical support and accompaniment provided by civil society organisations to municipalities and states in the implementation of the Migrant Child Protection Protocol on a state level.

- Broadening knowledge on promising practices implemented by participants. The Tenosique Protection Attorney shared practices regarding the attention given to migrant children, while the Comitan Child Villages explained their model of alternative care and demonstrated the effectiveness of an open-door space.

The event was positively evaluated by participants, and the need was highlighted to create similar spaces in order to share the work of counterparts in other states, as well as of federal and state institutions, in addition to how to articulate joint action.

The organising group will continue to strengthen capacity and provide technical support for the implementation of the Protocol together with alternatives to detention to the Protection Systems of the three states involved in the project. A second event of this kind is planned for 2023.

[1] The Commission for the Integrated Protection of Migrant Children and People Seeking Asylum, within the framework of the National System for the Integral Protection of Children, agreed on the Migrant Child Protection Protocol in 2019. The objective of the Protocol is to guarantee the rights of migrant children through articulation and collaboration between institutions responsible for their protection, and by identifying responsibilities and agreeing on forms of coordination.

Written by Elizabeth Alvares IDC Americas Programme Support

Monitoring the Situation of Migrant Children in Chiapas, Tabasco & Veracruz, Mexico

IDC's Americas Regional Programme is currently undertaking research into the situation of migrant children on the southern Mexican border. One of the objectives of this study is to explore whether children are indeed no longer detained due to their migration status, following the 2020 legal reform which prohibited their detention in immigration detention centres.

The initial findings of the study were recently presented in Mexico City, focusing on the following two research queries:

Confirm whether local authorities are familiar with the Migrant Child Protection Protocol (CPR), created in 2019 by a federal commission.

Verify the implementation of the Migration Law reforms, which prohibit the detention of accompanied and unaccompanied children in detention centres.

The first step in the research was to request public information and official responses with data and input from authorities who participate in the CPR and who attend to this population.

This was followed by on-site visits to three southern Mexican states to conduct interviews with authorities regarding their work procedures, as well as their strengths and weaknesses. In particular, we aimed to cross-check official data with reality.

Findings

The visits corroborated that state and municipal authorities have limited knowledge of the CPR, although it is worth mentioning that all do have reception and care procedures. Nevertheless, these are far from what is stipulated in the CPR, particularly regarding issues around inter-institutional communication and coordination, and hence the importance of implementing state protocols.

There is also an urgent need to strengthen the State and Municipal Protection Attorneys, who have limited human and material resources with which to fulfil their obligations as established by law. This is evidenced by the fact that international agencies, such as UNICEF and UNHCR, are currently paying the salaries of members of the multidisciplinary teams who carry out best interests evaluations and determinations.

In addition, there is insufficient capacity in the Centres for Social Assistance (shelters) to receive children referred by the National Institute of Migration, which impedes full compliance with the reform. Although certain funding was made available towards the end of 2021, beginning of 2022, this has been insufficient and has only enabled the reception of children in order to immediately return them to their countries of origin, lacking a human rights protection perspective.

One of the main and surprising findings of the study relates to where children are held, given that there is insufficient capacity to receive them. They were found to be held in so-called “referral offices,” created by the Instituto Nacional de Migración (INM). Children remain there until their migration procedure has been resolved, or until referred to the protection authorities. In many cases, this is done without an assessment of their situation and therefore without a determination of their best interest. In flagrant violation of the Migration law reform, at least in the states in which the research is being conducted, these offices are located next to detention centres and also depend on the INM. This contravenes the reform that prohibits the enabling of spaces for the detention of children in order to avoid the claim that children are not being held in detention centres.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that interviews with the Guatemalan and Honduran consulates in the region revealed that while they recognise the importance of the reform, they are concerned by the lack of institutional capacity to provide reception and care for the total number of children.

All authorities appear to be aware of the practices and significant shortcomings in service provision, and expect support and advice. It is notable that the work of those authorities that have collaborated with and received support from civil society organisations including IDC has advanced considerably in comparison with those who are more resistant and have not been open to such collaboration.

These findings underpin a second phase of advocacy in the three states, aimed at ensuring better practices.

By Pablo Loredo IDC Americas Monitoring & Evaluation Officer

Members of Congress and Civil Society Visit Chiapas, Mexico

The State of Chiapas is located in the south-eastern part of Mexico and shares a border with Guatemala. Tapachula is one of the 118 municipalities in the State, and is mainly subject to transitory migration, although is also a temporary and permanent destination for those seeking better opportunities and to safeguard their lives.

The city of Tapachula was chosen by the Colectivo de Observación y Monitoreo de Derechos Humanos del Sureste Mexicano (Human Rights Observation and Monitoring Collective in Southeast Mexico), the Grupo de Acción para la No Detención de Personas Refugiadas (Advocacy Task Force to End Detention of Refugees), and the Migration Policy Working Group, to host members of the Mexican Congress in order to highlight the rights of migrants and people seeking asylum. This was addressed considering the following four issues:

- the militarisation of borders and migrant controls

- unrestricted access to human rights

- the situation of children, and

- detention due to migration status

Three days of meetings with government actors, United Nations agencies, academia and civil society, as well as visits to detention centres (detention centres or provisional centres), shelters, and government agencies, confirmed the need for the Mexican government to undertake legislative reforms on a federal and state level to ensure an inclusive policy of migration and asylum that includes respect for human rights.

Some of the main concerns highlighted by the visit included:

- The vulnerability of migrants and asylum seekers, particularly, children, women, and members of the LGBTQI+ community

- The impact of militarisation and the presence of the National Guard in migration control

- The absence of institutions responsible for guaranteeing rights in migrant control and verification spaces, such as the Attorney for Protection of Children, and the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance

- The limited availability of information and obstacles to accessing migration regularisation processes and the recognition of refugee status

The situation in detention centres continues to be of great concern as living conditions of migrants and people seeking asylum have deteriorated due to the lack of dignified conditions, the absence of information, and in particular, the isolation and lack of expedited responses to applications. Furthermore, the difficulties faced by civil society organisations in accompanying and monitoring detention centres was also evident.

Members of Congress have undertaken to consider the following issues in the next legislative session:

- Harmonise legislation under the strictest standards of human rights protection.

- Eliminate the faculties of the National Guard in matters of migrant control and surveillance.

- Guarantee that applicants for international protection are not detained while waiting for a resolution by the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance.

- Expand the budget for the child protection system to guarantee the evaluation and determination of the best interests of the child, as well as the development of plans for the restitution of individual rights, under the highest standards of protection.

- Strengthen the response capacity of entities such as health, work, education, justice, and civil registry, amongst others, to include the migrant and asylum seeker populations in actions proposed by state and municipal governments.

- Establish efficient mechanisms of inter-institutional and transnational collaboration and referral between authorities, United Nations agencies, and civil society on a regional level.

- Promote and/or strengthen parliamentary controls that provide members of Congress with information on compliance with legal frameworks passed by Congress, particularly regarding migrant children.

A similar visit will be conducted in September 2022 in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, with four points of reflection and observation:

Mexico-United States binational policy

National and Public Security versus Human Security

Migrant children and asylum seekers

Accommodation

The Migration Policy Working Group believes that, on both a federal and state level, the Mexican Congress should modify legal frameworks to guarantee measures that ensure such human rights violations are not repeated. This is crucial given the recent events that occurred in the States of Chiapas and Texas, where migrants, seeking alternatives to avoid migration enforcement, were faced with death and desolation.

Written by IDC Partner Melissa Vertiz of the Migration Policy Working Group in Mexico, of which IDC is also a member

Hope in Efforts to End Detention of People Seeking Asylum in Mexico

People seeking asylum who apply for refugee recognition in Mexico while in immigration detention are required to remain in detention for the duration of their refugee status recognition process. However, should a person apply for asylum outside of detention, they will not be detained during their refugee status recognition process, given two conditions: first, that they remain in the federal entity (state) in which they are processing their application, and second, that they appear weekly before the corresponding authority to sign and declare their agreement to continue the process until a resolution is obtained.

Over the past decade, IDC and various organisations, such as Asylum Access México and networks such as Grupo Articulador México del Plan de Acción Brasil (GAM-PAB) and Grupo de Trabajo de Política Migratoria (GTPM), have promoted collective advocacy actions, initiatives and pilot programs for children to promote alternatives to detention (ATD).

On the basis of this and mindful of the severe injustice and harms endured in detention by people seeking asylum, in mid-2021, a civil society Advocacy Task Force against Detention was created to specifically advocate for an end to immigration detention of asylum seekers in Mexico.

The Task Force has focused on two activities: first, a campaign regarding the effects of detention on refugees and the need to eliminate detention for asylum seekers, aimed at raising awareness and promoting the prevention and elimination of detention in Mexico. Second, a proposal to reform several regulations in order to end this practice.

While the program allowing for the release of asylum seekers from detention has been implemented in the country since 2016 by the National Institute of Immigration (INM), the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR), and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (ACNUR), it remains an informal and discretionary practice without clear and public criteria, and at the end of 2020 it became subject to additional limitations. It is thus questionable whether the program can be considered an ATD.

All people seeking asylum are therefore at risk of detention at present. Children are an exception to this as their detention was prohibited, although not totally eradicated, by reforms in the Migration Law and the Law on Refugees, Complementary Protection and Political Asylum in 2020.

The legislative reform proposed by the Advocacy Task Force against Detention is ambitious, ranging from additions to the Constitution, to modifications of the Migration Law and the Law on Refugees, Complementary Protection and Political Asylum, among other initiatives. It aims to guarantee that asylum seekers are not subject to detention.

In 2022, the Advocacy Task Force aims to continue to raise awareness and advocate for the above-mentioned reforms. In addition, a series of actions are planned to promote the adoption of ATD for asylum seekers in both policy and practice, as well as to influence judicial decisions that will prevent detention and guarantee access to due process.

Written by Diana Martinez Americas Program Officer, Carolina Carreño Americas Childhood Project Officer & Elizabeth Alvares Americas Programme Assistant

Uncertain Future for Mexico's Asylum Seeker Release Program

The lack of clarity surrounding Mexico's asylum seeker release program (programa de salidas de la estación migratoria, SEM), together with the absence of public policy guaranteeing the rights of refugees, present significant obstacles for asylum seekers in refugee recognition procedures before the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR).

Migration authorities persist in increasingly and automatically detaining migrants and asylum seekers. In 2021, 307,679 people were detained, up from the 82,379 people detained in 2020, despite the pressure exerted by civil society organisations in the face of the national health emergency issued on 30 March 2020 by the federal government due to SARS-COVID-19. This pressure took the form of legal actions and advocacy to free vulnerable migrants and asylum seekers held in detention centres. During 2020, detentions continued and few asylum seekers had access to the SEM program. While the program was initially viewed as promising and as a positive practice, as access for detained asylum seekers became more restricted, it gradually dissipated and effectively came to an end,

The SEM is a tripartite mechanism between the National Institute of Immigration (INM), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (ACNUR), and the COMAR. It was first implemented in July 2016, with the aim of providing alternatives to detention for asylum seekers in detention centres.

The SEM benefitted 18,064 people between January 2017 and October 2020. However, in November and December 2020, only 145 people were able to access the program following new guidelines by the National Institute of Immigration (INM) to all detention center authorities. These instructions excluded people from the program if they had entered Mexican territory irregularly; if they were traveling alone, that is, without accompanying family, and had entered irregularly; or children who had entered irregularly. This evidently violates both Mexican law and international conventions that establish the international principle of not sanctioning asylum seekers for irregular entry.

New research on alternatives to detention for refugees in Mexico

In 2020, Asylum Access Mexico published a report on their research into the challenges and obstacles faced by asylum seekers in accessing the SEM program, as well as the process of applying for refugee status from detention. This research found that detention is in itself an obstacle to applying for refugee status in Mexico. In addition, those who applied for asylum when in detention, were forced to remain detained for an average of 40 days. In one case, a person was detained twice. They were initially held for a little over 40 days, followed by a further 2 months when detained in another city, even though they had been released from the original detention center under the SEM program.

The SEM also lacks clear criteria and transparency. As the program is neither institutionalised nor regulated, it is subject to discretion in its implementation and practically depends on the decision of the public official on duty. This discourages effective access to asylum. Ambiguity around how the program operates creates uncertainty for refugees. As such, many opt not to apply for asylum while in detention, as they understand that this will entail being held for prolonged periods. In this regard, people prefer to accept their deportation, despite the risk posed by being returned to the country from which they fled in the first place in order to safeguard their lives.

These findings reflect the urgent need to reform the refugee and immigration laws in Mexico in order to guarantee that immigration detention for people requiring international protection ceases to be an automatic and arbitrary practice, and is used only as a last resort in exceptional cases, with strict compliance to the criteria of necessity, proportionality and reasonableness of such detention.

By Alejandra Macías Delgadillo, Executive Director, Asylum Access Mexico & IDC International Advisory Committee Member

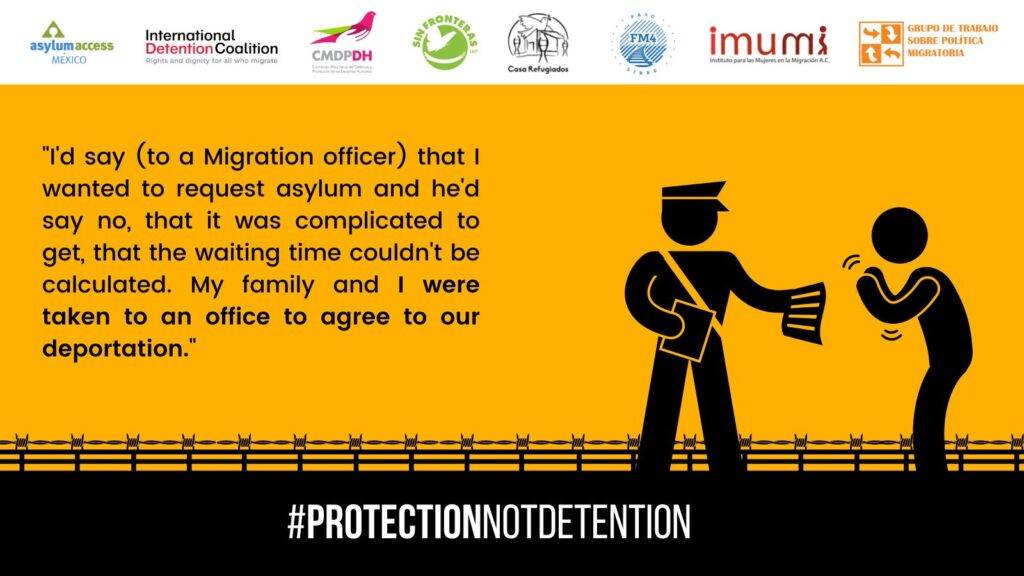

New Campaign to End the Detention of People Seeking Asylum in Mexico

IDC and Asylum Access Mexico, along with partners FM4 Paso Libre, Casa Refugiados, IMUMI, Grupo de Trabajo sobre Política Migratoria, Sin Fronteras, CMDPDH, and others, launched a campaign in November aiming to eliminate the detention of people seeking asylum in Mexico.

This campaign will work to raise awareness and advocate in favor of preventing and eliminating the detention of asylum seekers in Mexico, and will work to build a civil society advocacy movement to promote the issue of non-detention and the adoption of alternatives to detention (ATD). Advocacy goals will include changing law, policy and practice at all levels of government to make space for civil society to monitor and improve access to dignity, freedom and human rights for people seeking asylum and refugees in Mexico.

Follow @idcamericas and @idcmonitor on Twitter for more information about the campaign, and please view our campaign launch materials and feel free utilise them for your own context as well!

Immigration Detention in Trinidad and Tobago

Written by Denise Pitcher Caribbean Centre for Human Rights (CCHR) & Gisele Bonnici IDC Americas Regional Coordinator

Immigration detention policies and practices continue to be a serious human rights issue in Trinidad and Tobago (TT). Trinidad has experienced an influx of migrants, asylum seekers and refugees due to the ongoing humanitarian crisis in neighbouring Venezuela. In addition to the Venezuelan migrant and asylum-seeking population, over 40 other nationalities seek international protection in TT.

Trinidad and Tobago is party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol however the protections have not been included in national law and the country continues to treat the arrivals of migrants and asylum seekers under the 1976 Immigration Act. This law lacks provisions to treat the particular vulnerabilities and needs of those in need of international protection and to guarantee the rights of migrants. Consequently, persons that are found entering irregularly are charged with illegal entry without an individualised assessment of their cases thereby criminalising the asylum process.

It is in this context that serious instances of human rights violations occur with respect to immigration detention in TT. The strict application of the Immigration Act results in a reliance on detention to regulate migration in TT, leading to instances of arbitrary and indefinite detention. This reliance on immigration detention places legitimate persons in need of protection at further risk and exacerbates their already vulnerable situations. The Immigration Act urgently needs updating to adapt to the current context of migration in TT and more critically to ensure the protection of human rights of migrants and refugees.

People who are detained are placed in one of two immigration detention facilities. The original immigration detention centre at Aripo has been described by detainees as severely unsanitary and inhumane. Detainees are often forced to live in these conditions for months and even years. One detainee, from an African country, whose exact nationality is unknown, has been in this facility for over eight years and suffers from serious health conditions. It is difficult to ascertain the quality of care he is receiving or what legal support he has access to given the lack of access by civil society to the immigration detention facilities and the lack of independent monitoring.

The lack of independent monitoring in all places of detention is another critical issue as reports regularly surface, citing assault, lack of proper care and other abuses and it is impossible to independently verify the human rights situation of detainees in immigration detention and hold officials accountable. The Caribbean Centre for Human Rights (CCHR) recently received a report of a recognised refugee who had her government registration card confiscated (this card allows Venezuelans that have been registered with the government to live and work in TT) by an immigration detention official before she was returned to Venezuela. She was detained by the police along with her sister on suspicion of being involved in human trafficking. She was not allowed to challenge her deportation, as she was deported three days after being detained. This unfortunately is not a unique event but indicative of the standard practice and treatment by the state towards migrants and refugees. Another disturbing practice that has been reported is that before migrants, asylum seekers and refugees are deported they are made to sign forms that are in English without the support of interpreters. Some detainees may speak English and understand what they are signing, however the vast majority of migrants that are deported are Venezuelan nationals and so English is not their first language and they need support with interpretation.

Particularly concerning is the continued detention of migrant and refugee children who are often detained for several months. Even though international human rights standards and practices emphasise that children should not be detained for their migration status this is an ongoing practice by the government of TT. Notably, TT has ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child and established legislation to ensure the promotion and protection of children’s rights in the Children's Act. Currently, there are around ten children in immigration detention with one child detainee who is as young as two years old. Also of concern is that women and children are not separated from unrelated men at the immigration detention facility in Chaguaramas.

Immigration detention policies and practices in TT, particularly the absence of a legal framework to guide treatment of migrants and people seeking asylum, requires further scrutiny by the international community. Without accountability mechanisms, human rights violations will persist. CCHR makes the following key recommendations with regard to immigration detention and the use of ATD:

- The need for a refugee policy or legislation, or implementation of the Refugee Convention, which will reduce the instances of immigration detention because a policy/law will establish mechanisms for individualised assessments to identify persons in need of protection.

- The government should cease detaining children and adopt non-custodial, community-based alternatives to detention, relying on civil society and members of the migrant community to support with the care of migrant children.

- Adhere to the provisions in the Immigration Act, in particular to ensure that Special Inquiries happen after each arrest to ascertain whether the person should be subjected to detention.

- Increase the use of Orders of Supervision to mitigate a reliance on immigration detention, thus allowing persons to be released on an order of supervision under which they would be required to report to immigration division on a regular basis.

- Increase engagement with local and international stakeholders to develop a coordinated and holistic approach to immigration detention that prioritises the human rights of migrants and refugees.

- Train frontline state officials, police, magistrate, coast guard on human rights obligations with respect to migrants and refugees.

IDC stands by our partner CCHR in their recommendations, as well as their ongoing advocacy to protect the human rights of migrants and refugees in Trinidad and Tobago.

Haitian Migrants & US Immigration Detention

Written by Gisele Bonnici IDC Americas Regional Coordinator

IDC stands in solidarity with its members and partners in the US who are working tirelessly and urgently to address the injustice happening to Haitian people and families seeking refuge and safety at the southern border. Please read more in the Dignity Not Detention statement here.

Further, IDC is deeply concerned by measures of extraterritorial immigration enforcement, especially detention, as we seen with the reopening of the detention facility in Guantánamo Bay to detain Haitian migrants. Deportation and other push backs, as well as the externalisation of immigration enforcement, have been shown to obstruct access to basic due process rights, in particular the right to request asylum and to legal defence, and to cause aggravated harm to people at risk. IDC further expresses our concern for the decision to seek private contractors to operate the detention center on Guantanamo.

We will monitor this troubling situation alongside our members and partners in the US.