5 Years of the European ATD Network: Growing & Learning Together

In April 2022, members of the European ATD Network met for the first time since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Five years after the Network’s creation, its goal – to reduce and end immigration detention by building evidence and momentum on engagement-based alternatives – is more relevant now than ever before. Hannah Cooper, IDC’s Europe Regional Coordinator, reflects on some of the key takeaways from the meeting.

Recent years have shown increased momentum around alternatives to detention (ATD) in Europe, with a number of countries introducing legislative changes that have codified – and, in some cases, expanded – their use. Promising practice has taken the form of improved screening and assessment procedures, enhanced safeguards for people in vulnerable situations, introduction of legislation and policy that prohibits detention of certain groups, and the piloting of innovative ATD approaches (see IDC’s latest report released in May, Gaining Ground, for more promising practice in Europe and beyond).

Yet despite some steps forward, the need for effective, rights-based ATD remains great. Detention continues to be a key part of Europe’s toolbox when it comes to migration management and the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum is likely to result in increased use of detention – including arbitrary detention – due to its focus on border procedures and the push to increase and accelerate returns. While EU law states that detention should only be used as a measure of last resort and in very specific circumstances defined by law, detention is frequently applied as a default. Even where alternatives are used they tend to focus on enforcement-based approaches, which apply restrictions and conditions to control and track migrants, refugees and people seeking asylum. Such measures allow governments to monitor individuals and apply sanctions for non-compliance, but fail to support people in working towards resolution of their case. The conditions of such enforcement-based ATD are often unrealistic and put overly harsh burdens on migrants regarding reporting and bail conditions. In contrast, ATD based on engagement and case management in the community are more humane, collaborative, and effective in supporting people to work towards finding a temporary or permanent migration outcome, which can include regularisation, moving to a third country, or voluntary return.

It was with this in mind that the European Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Network came together in late April for our tenth meeting. Due to the pandemic, this was the first time that network members had met in person in over two years. The meeting’s overall purpose was therefore to provide network members from across Europe with the opportunity to gather after this long hiatus, review our progress to date, develop a joint understanding of the current context, exchange on priority areas and challenges, and develop a collective roadmap for the coming phase.

Working together to implement and advocate for rights-based ATD

Since 2017, the European Alternatives to Detention Network has been working to bring together organisations implementing case management-based ATD across Europe. The Network has grown from its initial four pilot projects, and now includes eight organisations in seven countries across Europe. Five years on, the goal of the Network – to reduce and end immigration detention by building evidence and momentum on engagement-based alternatives – is more relevant than ever.

The meeting in April provided Network members with a space to reflect, troubleshoot, and problem solve together. Our approach is constantly evolving – there are always new things to learn, and ways in which we can improve our delivery of rights-based ATD, based on the principles of holistic case management in the community. Given this, below are some reflections on the key takeaways from the meeting:

Learning together is key to growing together.

When the Network was formed in 2017, there were very few examples of case management based ATD happening. Detention Action’s Community Support Project (CSP), which works with young migrant ex-offenders who have experienced or are at risk of long-term immigration detention, was used as inspiration for other members, who initially had little experience in case management. The CSP was designed in line with the principles of IDC’s Community Assessment and Placement model, a holistic framework for case management that is drawn from social work principles. Today, through learning and working together, Network members are leading best practices on the provision of holistic case management, including when it comes to ATD.

Change happens, but slowly.

One of the network’s key priorities since its inception has been to influence ATD policy and practice across Europe. Network members are in a particularly strategic position to do this; their pilots work with groups experiencing some of the most severe vulnerabilities, and their ability to speak with policymakers from this on-the-ground perspective – combined with a solutions-focused approach – is one of the network’s unique strengths. Thanks in part to the advocacy of Network members, we have seen concrete impact – including the establishment of a specific role focusing on ATD and the adoption of the Screening and Vulnerability tools in Cyprus, and a partnership set up between the UK Home Office and non-governmental actors to test ATD approaches. However, change is slow and rarely linear. The Network is also only one part of a large ecosystem of change; as one participant put it, “we need to stop thinking we can change the world alone.”

Our work must always centre around lived experience leadership.

One of the central themes of this year’s Network meeting was how to ensure meaningful and responsible participation of leaders with lived experience of detention – not just as ‘users’ of services but also in leading the co-design and implementation of our pilots and projects. For all Network members, this is a current priority – and we discussed how resources can be put in place to ensure that leaders with lived experience are equal partners in the development of rights-based ATD, and can be supported to participate. The newest Network member, Mosaico, was established with this commitment in mind and their refugee-led approach has meant that migrants and refugees involved in the project are themselves active participants in its design and conception. Moving forward, the Network will be looking to further explore how we can promote lived experience leadership, in line with our two-year scaling plan.

We can see the impact of our projects, but we must do better at showing it to others.

Every day, Network members see the impact of their work. Whether this be ensuring that somebody is released from detention into a community-based pilot, or helping them to access the legal assistance that they were not able to obtain in detention - our projects have a concrete and visible positive impact on the lives of those at risk of immigration detention. We know, moreover, that ATD are better for people’s health and more cost effective than immigration detention, as well as being a far more effective and dignified way to support people to work towards resolution of their migration cases. And the evaluations from our projects (see here and here) present some of the strongest evidence for the success of ATD – with implications not just in Europe, but also for developing and enhancing ATD globally. Yet Network members agree that we must do better at showing the success of our projects as a whole, particularly to governments and policymakers but also to civil society allies, in order to provide concrete evidence that demonstrates the impact of effective, rights-based ATD.

Going forward, the Network will continue to evolve and adjust our approach in order to learn and grow together – finding ways to effect change, show impact, and shift power to those with lived experience. And by doing this, we hope that we will bring the Network one step closer to achieving our goal to reduce and ultimately end detention in Europe, allowing people on the move to live with freedom, rights, and dignity.

An Exploration of Accommodation Provision for Migrants in the EU

This blog is written by Rositsa Atanasova, Advocacy Expert at the Center for Legal Aid – Voice in Bulgaria, a European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN) member and ATD pilot implementer, and overviews the results of an EU mapping which demonstrates a wide variety of options when it comes to accommodation provision for migrants, including those that could be used within designated ATD initiatives.

In many national contexts the application of alternatives to detention (ATD) remains limited in practice, because detention is applied by default to foreign nationals who have lost the right of residence, and not as a measure of last resort. According to EU and international law, states must consider ATD before depriving people of their liberty. Yet too often we see an improper reversal of the burden of proof, whereby it is up to people in irregular situations to contest the presumption of detention by proving that they fulfil the requirements for the application of alternatives.

In Bulgaria, the experience of the Centre for Legal Aid – Voice in Bulgaria (CLA) is that there is almost no individualised assessment of the principles of necessity, reasonableness and proportionality, as required by European and international legal standards. Instead, authorities are only willing to consider ATD when an individual has met the conditions in the law for the implementation of alternatives through case management support. Frequently, this includes a requirement that suitable accommodation be available.

In order to better understand current accommodation options in the EU and Bulgaria, as well as their potential for expansion in the context of ATD, in late 2021 I carried out a study on options for irregular migrants. Here, I explain my conclusions as well as the implications when it comes to ATD for people in immigration detention.

Accommodation Options for Irregular Migrants in the EU

The study of accommodation options for irregular migrants, which I conducted for CLA with the support of our donor EPIM, consists of a mapping paper and an advocacy strategy. The mapping paper systematises current practice in the EU and advances a new conceptual framework for analysis of the link between ATD and accommodation. It is based on desk research and fills a gap in recent research on the accommodation of irregular migrants in the EU. The advocacy document, in turn, explores current practice in Bulgaria and contains an action plan for the short and mid-term in order to improve access to accommodation and expand the use of ATD. It draws on meetings with a range of stakeholders including government agencies and local authorities, NGOs, service providers and beneficiaries. The interviews provided information about the range of existing services, which was not available through desk research alone.

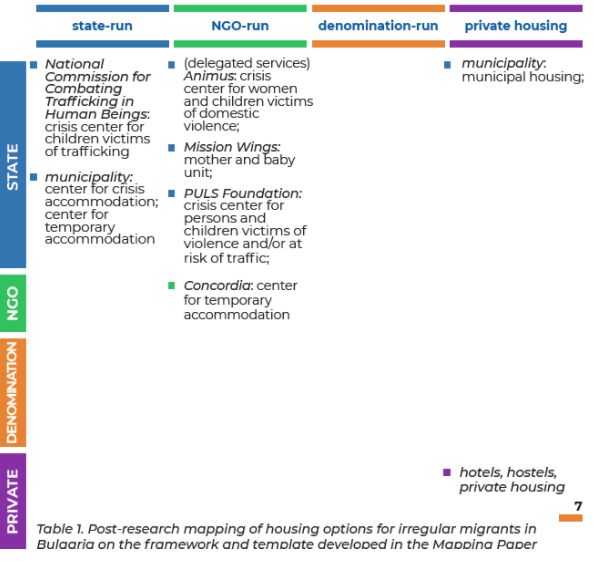

The range of accommodation options for irregular migrants in the European context can be mapped on a matrix (Table 1) in relation to the nature of the service provider and the nature of any potential partner. The axes represent a spectrum of accommodation provision, from state-run housing to private accommodation through NGO and denomination-run residential options. Such a model allows us to visualize dependency on an intermediary to access accommodation alternatives and how much of that service-provision is dominated by the state. In addition, the chart illustrates potential new areas for service-creation that might not yet exist. The matrix is ultimately also an instrument for measuring whether responses are mostly community-based or institutional.

As illustrated by the examples above, accommodation for irregular migrants in the EU, if available at all, tends to be institutional and oriented towards return. In exceptional circumstances, people who cannot be deported to their country of origin can be accommodated in open reception centres for asylum-seekers or in homeless shelters. These options, however, are not presented as possible ATD, but as a way for authorities to provide a bare minimum of material assistance. The different housing possibilities presented here are most often used by irregular migrants who are not in contact with the authorities. Such pathways, however, can be quickly and usefully deployed to offer alternatives to detention in an emergency situation, as illustrated by regularisation initiatives during the pandemic. This is why it is useful to consider the full range of available choices in an effort to expand the ATD portfolio.

Accommodation Options for Irregular Migrants in Bulgaria

The study of accommodation options for irregular migrants in Bulgaria reveals a gradually shrinking space, however. Access to state services, State Agency for Refugees (SAR) reception centers and municipal housing have become more difficult to access even for beneficiaries of international protection, not to mention those in an irregular situation. Service providers are less willing to bend the rules to accommodate people without documents in crisis, particularly in light of pandemic measures. Mothers with children and victims of domestic violence or trafficking are the only groups that face fewer impediments, but even their access frequently involves protracted negotiations with service providers and social workers to renew referrals on a case by case basis. Placement in a service, ultimately, does not qualify as a formal ATD, but amounts to tolerated stay that is not formalized in any way.

Private housing remains the most readily available option for irregular migrants and the only one that currently qualifies as a formal ATD. The advantage of the Bulgarian system is that those who lend property to people without documents do not seem to incur criminal or administrative sanctions, in line with FRA recommendations. As a downside, private arrangements are onerous due to the need to find a guarantor who is willing to provide financial support, as well as to locate suitable accommodation amidst exploitative renting schemes, discrimination and limited choices.

Implications for ATD

The results of the mapping and advocacy strategy, outlined above, demonstrate a wide variety of options when it comes to accommodation provision for migrants, including those that could be used within designated ATD initiatives. On the face of it, the Bulgarian accommodation requirement mentioned above could potentially be good news because it opens up the space for NGOs to develop accommodation options and case management programs for irregular migrants in order to expand the use of ATD for those at risk of immigration detention. Moreover, we know how essential stable and appropriate accommodation is for those going through migration processes; the government requirement could be seen as a recognition of this. By drawing on lessons learned across the EU, and developing additional accommodation models, the implication is that advocates for the rights and liberties of migrants can encourage a shift on the part of governments to using ATD.

The reality, however, is more complex. Given the standing presumption of detention in Bulgaria, it is not clear whether the availability of more housing options for irregular migrants will necessarily lead to greater application of alternatives. Instead, it seems that the accommodation requirement is being used as an excuse to justify the government’s failure to systematically consider ATD, linked to a general political resistance to community-based solutions (including on national security grounds).

CLA practice indicates that authorities tolerate stay in services when it will spare them the responsibility for vulnerable individuals and are more willing to apply ATD when presented with ready-made solutions. The implication, therefore, is that whilst accommodation remains a key part of ATD programmes, the provision of more accommodation options alone is unlikely to be the catalyst for change that it might seem at first glance to be. Provision of accommodation, whilst a key part of ATD, is certainly not a silver bullet. Instead, the reversal of the ATD logic – which sees detention as the primary precautionary measure, as opposed to a measure of last resort – should be challenged on its own terms. In particular, it is essential that the burden of proof is turned back around so that presumption of liberty, rather than detention, becomes the norm. In Bulgaria, possible routes lie in advocating for access to services on the basis of the new Law on Social Services, which is theoretically applicable to all persons within the jurisdiction, and NGOs stepping in as mediators, guarantors or service providers for irregular migrants.

IDC is a co-coordinator of the European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN), and this blog was originally posted on the EATDN site here. Find out more about the work of Centre for Legal Aid – Voice in Bulgaria, including their pilot ATD programme here.

The Action Access Alternative to Detention Pilot: Evaluation of Community-Based Support

An independent evaluation of the pioneering pilot project delivered by European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN) member Action Foundation and funded by the UK Home Office has found it is more humane and significantly less expensive to support women in vulnerable situations in the community as an alternative to keeping them in detention centres. In this blog, Action Foundation Chief Executive Duncan McAuley summarises the pilot, its aims, and the findings of the evaluation.

In 2018, the UK Government published the Shaw Progress Report, a follow-up to the Review into the Welfare in Detention of Vulnerable Persons produced by Stephen Shaw, former Prisons and Probations Ombudsperson for England and Wales. Amongst other recommendations, the progress review urged the UK Government to “demonstrate much greater energy in its consideration of alternatives to detention.” Shortly after its publication, the Government announced the creation of a Community Engagement pilot (CEP) Series, which set out to test approaches to supporting people to resolve their immigration cases in the community.

Action Access: a civil society-government partnership

Following a successful bid process, Action Foundation – which had played a key role in the advocacy efforts that led to the introduction of the CEP – was granted the contract for the first of the four pilots, and our Alternative to Detention (ATD) project was born. The Action Access pilot ran between 2019 and 2021 and supported 20 women seeking asylum in a community setting in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in the North East of England. With one exception, prior to joining the pilot all of the women had been detained in Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre.

Upon joining the pilot, the women were provided with shared accommodation, received one-to-one support from Action Foundation staff, and were supported to access legal counselling. Although it wasn’t a requirement of the pilot, the women also benefited from Action Foundation’s broader program of activity such as its free English language classes and weekly community gatherings, facilitating socialisation, signposting and referrals.

The pilot was framed around five pillars of support:

- Personal stability: achieving a position of stability (in relation to, for example, housing, subsistence and safety) from which people are able to make difficult, life-changing decisions;

- Reliable information: providing and ensuring access to accurate, comprehensive, personally relevant information on UK immigration and asylum law;

- Community support: providing and ensuring access to consistent pastoral and community support, addressing the need to be heard and the need to discuss their situation with independent and familiar people;

- Active engagement: giving people an opportunity to engage with immigration services and ensuring that they feel able to connect and engage at the right level, enabling greater awareness of their immigration status, upcoming events and deadlines with routine personal contact fostering compliance; and

- Prepared futures: being able to plan for the future, finding positive ways forward, developing skills in line with their immigration objectives, identifying opportunities to advance ambitions. Through this approach, the pilot hopes to provide more efficient, humane and cost-effective case resolution for migrants and asylum seekers, by supporting migrants to make appropriate personal immigration decisions.

The model was innovative in a number of ways. The combination of a holistic approach to case management with comprehensive legal support, for instance, was integral to the delivery of the pilot and seen to make case resolution more likely. In addition, although there have been other examples of ATD in the UK, including an ongoing project run by Detention Action, Action Access was the first time that such a pilot had been built from a formal civil society-government partnership. The relationship between many parts of the Home Office and civil society are often tense, and the pilot represented a leap of faith. But we found the experience of working with the Home Office Community Engagement Team a really positive and productive one. There was a genuine collaborative relationship between the Home Office, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and Action Foundation and this unique partnership demonstrates a model of working that is both dynamic and effective. Importantly, it demonstrates the success possible if the Home Office is willing to replicate this approach in the future.

Evaluating the pilot’s success: Improved wellbeing and reduced costs

The findings of the pilot were officially published in late January by UNHCR, who had commissioned the evaluation. The report, entitled Evaluation of the Action Access Pilot, was researched and compiled by Britain’s largest independent social research organisation, the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen). Commenting on the effectiveness of the pilot, NatCen’s report states:

“Our evaluation found qualitative evidence that participants experienced more stability and better health and wellbeing outcomes whilst being supported by Action Access in the community than they had received while in detention. Evidence from this pilot suggests that these outcomes were achievable without decreasing compliance with the immigration system.”

The evaluation said this provided “a more humane and less stressful environment for pilot participants to engage in the legal review and make decisions about their future, compared with immigration detention. Even when those decisions were difficult and participants had no legal case to remain in the UK, the pilot gave the participants space and time to engage with their immigration options.”

The more humane environment was a repeated theme shared with researchers, with one of the participants saying, “In detention, you don’t have this kind of positive atmosphere. You just want to cry. You just want to stop eating. You just want to kill yourself. This is because you are so in trouble there, right. Then, when you come out, it’s like everything is going to be nice again… the atmosphere is very different, and I think you recover yourself.”

The evaluation of Action Access also suggests that keeping people in the community is much less expensive than holding an individual in detention. The report states that the potential savings could be less than half the cost of detention, in line with Action Foundation’s own calculations.

Next steps: Introducing ATD as ‘business as usual’?

While Action Access may have come to an end, Action Foundation continues to work according to the same model: combining one-to-one case management with comprehensive legal advice in order to ensure that people are able to resolve their cases in the community. We continue to believe that this type of community-based support is the best way of supporting people going through the migration system and can be used effectively instead of detention.

As for the UK Government’s next steps, it remains to be seen what will come of the CEP Series in practice. A second pilot is already underway, run by the King’s Arms Project, however there have been no confirmations that the CEP series will continue beyond this.

The seven recommendations made in the Action Access evaluation, all of which the Home Office has accepted, included a call for them to “accelerate the introduction of effective aspects of the ATD programme into the Home Office’s ‘business as usual’ model.” We hope to see progress on this, and the upcoming International Migration Review Forum (IMRF) could be the perfect context to pledge to take action. In the UK as is the case elsewhere, there’s a growing need for a change of direction and a rethinking of the approach to migration management – particularly when it comes to immigration detention. We hope our pilot, and the evidence that has emerged from it, can contribute to those necessary changes.

IDC is a co-coordinator of the European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN), and this blog was originally posted on the EATDN site here. Also find out more about the Action Access pilot here and here.

IDC Statement on the Crisis in Ukraine

Published on Friday 4 March, 2022

It’s been just over a week since the Russian government initiated a military invasion of Ukraine, and civilians are continuing to flee their homes in response to ongoing airstrikes, shelling, and ground fighting. According to the United Nations, as of 2 March more than one million people had fled the country in search of safety, many on foot in bitter cold temperatures - including tens of thousands of families with young children and infants. International Detention Coalition (IDC) stands firmly in solidarity with all those who have been impacted by this conflict, and we unequivocally condemn the Russian military invasion of Ukraine.

The largest numbers of refugee arrivals have been seen in Poland, Hungary, Moldova, Slovakia and Romania. The response of these governments has so far been overwhelmingly positive, with the Polish Interior Minister declaring that the country would take “as many [people] as there will be at our border,” and both the Hungarian and Moldovan governments pledging to keep their borders open to those fleeing the conflict in Ukraine. Local communities have also shown great generosity and hospitality; nine out of every ten refugees in Poland are being hosted by friends or family.

At the EU level, on Thursday the decision was taken to offer temporary protection to refugees fleeing Ukraine by triggering the temporary protection directive, which was drawn up in 2001 following the conflicts in the Balkans but has so far never been used. The Directive allows for people fleeing a particular country or area to be granted status for up to three years, without having to formally lodge an asylum claim. Other countries across the world have also shown their support for those affected by the conflict.

For IDC and its members, this positive response provides further evidence that immigration detention is not a necessary or integral part of migration governance systems at all. When governments prioritise creating a welcoming and safe environment for those fleeing war and persecution, people can seek sanctuary without being detained, and crucially with their human rights and liberty intact.

However, concerning reports have emerged of African migrants and other migrants of colour, including international students studying in Ukraine, being blocked or delayed from fleeing to safety. This is unacceptable. Moreover, at its border with Belarus the Polish government continues its project to construct a wall to deter migrants and those seeking asylum from crossing. This follows months of aggressive pushbacks by the Polish authorities of people seeking safety, many of whom are migrants of colour, which have led to the deaths of at least 19 people. Regardless of sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, and racial, ethnic, religious, and national background, it is essential that all those fleeing conflict are able to exercise their right to seek asylum and their right to freedom of movement. Governments of receiving countries must provide a welcoming atmosphere, documentation and access to services to those arriving in search of peace and safety from Ukraine and elsewhere.

Overall, the regional and international response to the crisis in Ukraine has so far demonstrated that “Refugees Welcome” can be more than a slogan. As the crisis continues to unfold, IDC urges all governments to sustain the support and assistance that they have generously extended to so many fleeing Ukraine, and ensure this support is delivered to all people with equity and compassion. We also encourage governments to learn from this situation in order to inform their future responses to war and crises which force refugees and migrants to seek safety at their borders – no matter where people are from.

To the people, families and communities whose lives and futures have been impacted and uprooted by the conflict in Ukraine, we stand with you during this heartbreaking and challenging time.

IDC members are actively responding to refugees arriving from Ukraine:

- In Poland, The Association for Legal Intervention (Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej - SIP) works to ensure that migrants and refugees in Poland are able to access their rights. See here for more information on accessing legal support and crossing the border into Poland. Other information can be found in Polish, Ukrainian, Russian and English here.

- In Romania, the Jesuit Refugee Service is providing support to people arriving from Ukraine by providing welcome packages, channelling donations to people in need, and supporting people with accommodation and onward travel. Find out more and donate here.

- In Hungary, the Hungarian Helsinki Committee is providing support and legal assistance to those fleeing Ukraine. They have produced information packs for refugees in Hungarian, Ukrainian, Russian and English that can be accessed here. For more information on their response and to donate, click here.

More information on the ongoing crisis, and regular situation updates, can be found on the UNHCR Help page and the Operational Data Portal for Ukraine.

From Enforcement to Engagement: Scaling Up Case Management as an ATD in Europe

Written by Hannah Cooper IDC Europe Regional Coordinator

Across Europe, there is pressure to increase the use of immigration detention as part of a push to accelerate return rates and reduce irregular migration. The horrifying scenes emerging from the Polish-Belarusian border or the recent tragedy in the English Channel are part of a trend amongst many European countries to use whatever means are at their disposal to push back, deter and contain people arriving at their borders - many of whom have fled their own countries in fear for their lives. Governments are curbing human rights and detaining people in often inhumane conditions, destroying the lives of individuals, their families and communities.

We know that detention is harmful to people’s mental and physical health, it is also ineffective, and expensive for governments and authorities. EU law states that detention should only ever be used as a last resort and in specific circumstances, yet frequently countries use detention by default, and this is on the rise.

Since 2017, the European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN) has been advocating for an end to immigration detention through piloting community-based alternatives to detention (ATD) and showcasing their effectiveness. The EATDN believes people don’t need to be deprived of their liberty during the immigration process and that there are better solutions than detention.

Over recent months, supported by IDC and PICUM, the EATDN has been working together to develop a plan to guide our work over the coming years. As part of working towards its goals, the EATDN sees a need to expand and amplify its pilots and this plan sets out a roadmap for how the Network will scale case management projects and community-based ATD for people who are at risk of detention.

Through this planning process, EATDN members have reflected on our collective progress thus far, taking into account internal and external achievements and set-backs, and reflecting on how the network can achieve more social impact by increasing its geographical scope, fostering partnerships with new actors, influencing social and political institutions, reaching more people and resolving more cases. The plan details our four objectives:

- Network building: Strengthening our relationships and expanding our networks will help to scale up our projects. Working collaboratively with governments, authorities, legal experts, communities including leaders with lived experience, and civil society will intensify our work to reach more people and contribute to resolving more cases.

- Geographical expansion: In the next two years, as well as establishing additional engagement in the areas we already work in, we aim to expand to several additional cities and one additional country. This way we will demonstrate to more governments that community management is the best solution.

- Expansion beyond groups experiencing vulnerabilities: We are extending our reach beyond women and families to reach those who are already in detention and those who are not identified as experiencing vulnerabilities.

- Increasing numbers: Within two years, we will increase the number of people we support with community-led management by 10-20%.

This scaling will be supported by a focus on advocacy, research, network-building, peer learning and the leadership of those with lived experience of detention. In this implementation plan, the EATDN lays out how these different elements of its work will be organised and implemented over the next two years in order to promote community-based solutions as well as expanding and amplifying case management-based ATD. Ultimately, our goal is to work towards ending immigration detention by providing strong evidence that migration management frameworks that do not include detention are feasible and effective. Our scaling plan outlines how, by broadening and deepening our work, we are creating sustainable change now and into the future. The EATDN’s two-year implementation plan for scaling can be read in full here.

Training Georgia’s Migration Department on Engagement-based ATD

Written by Hannah Cooper IDC Europe Regional Coordinator & Min Jee Yamada Park IDC Asia Pacific Programme Officer

In mid-June, IDC was invited by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) in Georgia to deliver a two-day training session to officials of the Migration Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

The aim of the training was to increase the practical knowledge of Georgian Migration Department officials on Alternatives to Detention (ATD). The training specifically focused on how community-based case management can be used to reduce and prevent detention, and provided guidance on how such an approach can be translated into the Georgian context. Migration Department officials gathered in Tbilisi to attend the training, with IDC trainers joining online due to COVID-related measures.

The training covered the following four modules:

- Introduction to ATD - definition, trends, and benefits

- Key components of successful ATD

- Community-based Case Management

- Implementing ATD – Knowledge to Practice

Participants also had an opportunity to delve into case studies from other countries where ATD are successfully implemented and evaluated. Experts from two IDC member organisations – the Association for Legal Intervention (Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej, SIP) in Poland and the Cyprus Refugee Council – were invited to brief the Georgian officials, and to set out their ongoing work piloting case management-based approaches with a view to ending detention. These organisations are both part of the European Alternatives to Detention Network, a group of NGOs across Europe that is building evidence and momentum on engagement-based alternatives to detention, in order to reduce the use of immigration detention in Europe.

Post-training feedback from participants showed a dramatic increase in the knowledge of migration officials when it comes to ATD, relevance to their work, as well as an increased awareness of practical mechanisms for implementing ATD that are based on a community-based case management model that has at its core respect for the dignity and rights of all migrants. Participants also commented positively on the new insights they had gained around the role that civil society organisations can play in implementing ATD effectively.

This training was delivered as part of a long-standing capacity building programme on ATD that IDC offers, and will now develop further in order to provide governments and other actors interested in ATD approaches a curated and tailor-made training experience. More information on IDC’s ATD Training Programme can be found here.

How the UK Turned Away from Immigration Detention

Written by Jerome Phelps

Strategy and advocacy consultant, and former Director of International Detention Coalition and Detention Action

The summer of 2013 was a very different world. President Obama was on course to sweep to a second term. ‘Brexit’ was a neologism likely to be forgotten. Mayor of London Boris Johnson was directing his attention to bendy buses and the garden bridge. The Mediterranean was a summer holiday destination, rather than a mass grave for migrants, and pandemics were just one more distant anxiety.

It was also the time that the UK’s use of immigration detention peaked, with over 4,000 migrants bedding down every night in the 12 detention centres, and countless prisons, around the country. The Home Office had opened five new detention centres since 2001, and was developing further plans to expand to 5,000 detention places.

The last seven years have been a time of catastrophic setbacks for progressive politics and human rights. Yet in the same period, under a series of Conservative governments consumed by reducing migration and propagating anti-migrant rhetoric, the UK has turned decisively away from its obsession with immigration detention.

A political problem

Even before the pandemic, the numbers of people in detention had dropped by around 60%, to 1,637 at the end of December 2019. Asylum-seekers are no longer routinely detained throughout the process on the notorious Detained Fast Track, suspended since June 2015 and dead in the water. While the UK has not followed Spain in emptying its detention centres during the pandemic, numbers have dropped further, to 313 in May 2020. The Government has announced that Morton Hall detention centre in Lincolnshire will cease operating next year and return to being a prison, the fifth detention centre to close since 2015. Since August 2020, the notorious Yarl’s Wood is no longer used as a detention centre; given its low rate of occupancy over the last two years, it is doubtful whether it will return to its former use.

Detention is now generally seen as a political problem. Ministers have stressed that the reduction in detention places ‘is a key aspect of the series of reforms the government is making across the detention system’, and emphasised that the Government is ‘committed to going further and faster in reforming immigration detention’. Instead of boasting of toughness in locking up ‘foreign criminals’, Ministers speak of piloting community-based alternatives to detention with civil society. Senior Conservative backbenchers, including Andrew Mitchell and David Davis, are leading calls for a 28-day time limit.

The battle is not won. 300 is still far too many people for the Home Office to seek to detain throughout the pandemic, while returns to most countries of origin are impossible. The Home Affairs Committee in July 2020 found it ‘troubling’ that 40% of people still in detention had indicators of significant vulnerability and risk from Covid-19. Despite sustained cross-party political pressure, the Government still refuses to introduce a time limit: the UK remains isolated in Europe in practising indefinite detention.

Nevertheless, a major reversal has taken place in the direction of travel of UK detention policy, which is antithetical both to regional trends in the EU, and to the Home Office’s overall approach to migration. It is important to understand how the tide of expanding detention was reversed, particularly at a time when the pandemic is posing unprecedented opportunities for a radically reduced detention system.

Civil society mobilisation

It is no coincidence that the period of this shift coincided with sustained civil society mobilisation and collaboration to delegitimise the use of detention. My analysis of the detention reform movement over last ten years, based on interviews with key stakeholders and published here, finds reason to believe that the collapse in government confidence in detention is to a large extent the result of civil society campaigners, including migrants themselves, simply winning the argument.

External factors helped this change, but are not enough to explain it. Home Office budget cuts were certainly a factor – detention is hugely expensive. But governments can always find money for political priorities, as the Covid-19 response is again demonstrating. The Panorama revelations of abuse by detention centre guards, along with the shock of the Windrush scandal, had a toxic effect on the legitimacy of detention – but only because that legitimacy was already under intense scrutiny. Previous scandals in the noughties had had little political impact.

What changed was sustained and effective pressure from civil society. Campaigners, charities, faith groups, lawyers, individuals, institutions and (crucially) migrants with experience of detention collaborated strategically over many years to transform the political debate. They succeeded in both making detention a political problem, and in setting the narrative for other actors to follow.

Effective tactics

Campaigners told a consistent and compelling story about the injustice of indefinite detention and the need for a time limit. It was a story that could reach new and influential audiences beyond the migrants’ rights movement, without alienating core supporters by watering down messaging in pursuit of the political middle ground. The story was told in different ways by migrants protesting in Yarl’s Wood, by faith leaders making public statements, and by HM Inspectorate of Prisons in their monitoring of detention centres, but the central narrative and demands were the same. This narrative of individual liberty from arbitrary state power has traction across the political spectrum, even where there is hostility to migration and human rights. Yet it could still mobilise the passionate supporters of migrants’ rights, including migrants themselves, without whom the issue would have remained marginal.

At the core of this process was the Detention Forum, a diverse network set up in 2009 to challenge the legitimacy of detention. The Forum was by no means responsible for all the crucial interventions, and tactfully never sought to be a high-profile public actor in its own right. But its wide membership across the country to a large extent came to base their tactics on the shared strategy and theory of change of the Forum, and doubtless few actors working on detention reform were not in close contact with at least one Forum member.

There was no single campaign for detention reform, and no-one owned indefinite detention as an issue. NGOs ran different campaigns around particular groups in detention; protests highlighted particular issues; messaging was not centrally policed, and varied considerably. But hashtags were shared, open source materials developed, and many Forum members spent considerable time on the telephone or on trains to engage and support groups around the country to get involved. New groups were free to pick up the issue and campaign in their own way; some joined the Forum, others didn’t. In practice, most people most of the time were telling versions of the same, compelling, story.

All this was, to an extent, foreseen by the Forum. A protracted, painful and distinctly sobering strategy exercise throughout 2012 identified that Forum members had none of the necessary contacts to convince Ministers or the Home Office to change. Detention NGOs and campaigners emphatically did not have the ear of government, and neither did their friends. So a strategy was developed to build a broad civil society coalition, involving allies with more authority – politicians, faith leaders, institutions.

Having a wide range of allies meant that a wide range of tactics could be used in different spaces and times. The Detained Fast Track was resistant to both campaigning and government advocacy (it was seen to ‘work’ in getting asylum-seekers removed, so there was no interest in finding out whether it was doing so fairly), but it proved vulnerable to a wide-ranging legal challenge by Detention Action. City of Sanctuary could bring to the issue communities around the country who cared about asylum, while These Walls Must Fall mobilised grassroots groups for radical activism at the local level. Visitors groups and legal and medical organisations gathered and analysed the evidence of the harm of the detention that was the basis of everything else.

Crucially, the movement was initiated and increasingly led by people with experience of detention. Indefinite detention had become normalised because it was applied to non-people: the ‘foreign criminal’, the ‘bogus asylum-seeker’. It became problematic because people stepped out from behind these dehumanising tags and told their stories, not as victims but as experts-by-experience able to offer policy solutions. The initial push for a campaign against indefinite detention came from migrants in detention. Early reports and campaigning foregrounded their powerful testimony about their experiences. By the time of the parliamentary inquiry in 2015, which brought unprecedented cross-party political pressure and media interest to the issue, experts-by-experience were the dominant voices, both at the evidence sessions of the inquiry and in the subsequent media coverage.

As pressure grew for change, it became possible to talk constructively to the Home Office about how they could move away from over-reliance on detention. The organisation I was leading at the time, Detention Action, was piloting a community-based alternative to detention for young men with previous convictions, demonstrating that they could be effectively supported in the community. UNHCR facilitated high-level conversations with the Swedish and Canadian governments about their own community-based approaches. The Home Office began to informally collaborate with our pilot, and gradually moved towards committing to develop alternatives.

As political pressure over indefinite detention grew, the Home Office repeatedly refused to introduce a time limit, or even to acknowledge that it practiced indefinite detention. But in 2015 it began closing detention centres, and it has continued closing them. In 2018, the Home Secretary promised in Parliament to work with civil society to develop alternatives, the beginning of a small but growing programme of pilots.

Long-term transformation

This points to the key challenge facing detention reform. Progress so far has been based on winning the argument on detention as a relatively niche sub-issue, while the toxic politics of xenophobic migration control continued elsewhere. But a sustainable long-term shift away from detention needs to be part of a wider shift in migration governance away from enforcement, towards engagement with migrants and communities. If detention is simply replaced by a hostile environment that excludes and abuses migrants in the community, it will be a pyrrhic victory.

However, the hostile environment has not been a success, from the Home Office’s own point of view: numbers of returns, including voluntary returns, have been dropping for several years. Alternatives to detention point the way to a potential long-term transformation of migration governance, towards a system based on the consent of communities and treating migrants with fairness and dignity. Such a system would have to look very different from the current one. The Government will not sign up to such a shift immediately. But the pandemic has made clear that society is as vulnerable as its most excluded members. Civil society will need to lead if we are to build back better; the detention reform movement provides some clues as to how.

Jerome’s paper ‘Immigration Detention Reform in the UK 2009-19‘ is available here

This article was originally published on The Detention Forum website on September 2, 2020.

New Evaluation Report: Building a Culture of Cooperation Through ATD in Europe

Written by Barbara Pilz and Mia-lia Boua Kiernan

Finalised in June, this report marks the end of a 2-year evaluation period of engagement-based alternative to immigration detention (ATD) pilot projects in Bulgaria, Cyprus and Poland. What can new data tell us about the pilots’ impact on individuals and their migration processes?

Why Evaluate?

Thorough evaluations of case management pilots can measure success factors at both personal and strategic levels. When it comes to individuals who are going through a migration process, evaluations measure the pilot’s impact on a person’s capacity and agency to work towards and stay engaged in their own case resolution. With regards to strategy, evaluations generate learning and evidence that contributes to national and regional discussions on reducing and ending immigration detention through the use of engagement-based ATD in the community, which is also one of the central goals of the EATD Network.

This particular evaluation measures the impact of case management on peoples’’ behaviour, approach and outlook over time. The evaluation also identifies the barriers to case resolution and makes recommendations for how case management processes and procedures can overcome these challenges. Further, the evaluation analyses whether the pilots have achieved the full benefits of ATD in terms of cost, compliance and well-being.

“A sustained and collaborative process of reform, based on the learning of the pilots and involving structured collaboration among governments, migrants, civil society and other actors, could deliver systemic improvements that would benefit all stakeholders.” (p. 3)

As part of this ongoing evaluation, an interim evaluation report was also published in 2018.

A Unique Exercise

The framework developed for this evaluation is the result of vigorous assessment and learning, and has been shaped through ongoing conversations, testing, and adjustments. This novel framework is part of a new social policy area that aims to guide ATD in order to resolve cases in a fair, timely, and humane manner based on people’s active engagement in their own cases.

This second evaluation is based on data collected in 2019, two years after the launch of the ATD pilot projects. When compared to the interim report, this evaluation brings more robust qualitative analyses due to a larger sample of qualitative data.

“The evaluation, on the whole, seeks to find commonality of impact of case management across the pilots rather than differences between the pilots. […] The evaluation aims to go beyond the basic quantitative questions that are frequently asked of ATD programmes, to understand at a qualitative level why ATD is or is not effective in helping individuals” (p.6)

With this intent in mind, the evaluation highlights that the purpose of the pilots is not to produce perfect quantitative results, such as fully avoiding absconding at any cost. Instead, pilots are stronger when their programming embodies a deep understanding of the complexity of case management interventions, their diverse contexts, needs and desired outcomes. Even when case management does not reach the intended result, understanding why things do not go according to plan is just as important as recognising when they do.

Evidence for Advocacy

In general, it’s a new practice to use case management to implement and evaluate community-based ATD. Evaluations provide an opportunity for implementers to learn from each other, and to regularly reflect on the complexity of their work on the ground.

Qualitative evidence from pilot evaluations can feed directly into strategic advocacy. Governments, civil society organisations and other stakeholders need qualitative evidence to uncover the true benefits of case management and encourage continuing and new practice of ATD. This advocacy leads to much needed migration management systems change that prioritises and values engagement over enforcement.

The three pilots are part of the European Alternatives to Detention Network alongside similar projects in Belgium, Greece, Italy, and the UK. This evaluation was commissioned by the European Programme for Integration and Migration (EPIM) and executed by Eiri Ohtani. To learn more about the pilots, the methodology, and key findings read the full report here.

Originally posted on European ATD Network website.

Practical Steps & Guidance on ATD: Council of Europe

The Council of Europe has published a new handbook outlining key principles and processes to implement alternatives to detention (ATD) in the context of migration. What does it add for civil society working to reduce immigration detention through alternatives?

From theory to practice

The Practical Guidance on Alternatives to Immigration Detention: Fostering Effective Results is based on the Council of Europe’s in-depth Analysis of legal and practical aspects of effective alternatives to detention in the context of migration, adopted in 2018. But its central focus is practical implementation. The handbook aims to help fill the implementation gap in relation to ATD by providing “concise and visual” user-friendly guidance to governments on how to develop alternatives that allow states to manage migration without over-reliance on detention.

A focus on process

Within this practical focus, a key innovation of the new guidance is that it looks at processes for developing alternatives to detention. Recognising the need for context-specific actions and tailor-made approaches, it sets out key questions and steps that are at the heart of a developing successful ATD. This includes questions for scoping national contexts and practical steps for governments to plan and test new programmes – manageable steps that governments could take to start moving away from detention. This is a welcome shift from the common focus on ‘examples’ of ATD, given that there are no one size fits all transferable models in this field.

Image of the report by the Council of Europe in 2019

Image of the report by the Council of Europe in 2019

Reinforcing need for trust and support

The Practical Guidance reinforces the need for trust and support in alternatives to detention that ensure dignity and rights, while better achieving government migration management goals. It uses the six essential elements of effectiveness identified by the Analysis and underscores that a “central cross-cutting element for the effective implementation of alternatives to detention is building trust […] through a spirit of fairness and mutual co-operation”. As a practical step, the handbook suggests meaningful consultation with diverse stakeholders, particularly migrant communities that may support individuals to engage with immigration processes.

Growing momentum

As such, it contributes to growing emphasis regionally on engagement-based alternatives. This was evident, for example, at a conference on Effective Alternatives to Detention of Migrants held in Strasbourg in April 2019. The conference was attended by over 200 participants, mainly representatives of national governments, with high-level participation from the European Commission and Council of Europe organisers.

A milestone event in terms of ATD, the ‘key messages’ from the conference include that “to be effective, alternatives to detention should adopt a holistic and person-centred approach based on responsibility and trust” and that “there is space to adopt engagement-based methods to a greater extent, including dedicated case management that can enhance effectiveness”.

Contributions and way forward

The Practical Guidance was adopted by governments for governments, through the Council of Europe’s foremost human rights body; the Steering Committee on Human Rights. With its focus on trust-based approaches and process for practical implementation, it could prove to be a useful tool for NGOs advocating for engagement-based alternatives as part of a strategy for change on detention.

Read more news about Europe:

Turning the Tide of Detention: What Role Can European Cities Play?

Written by Barbara Pilz and Jem Stevens

European cities are increasingly involved in debates around migration governance. What role could they play in building systems based on engagement with people, not enforcement and immigration detention?

Not just for national governments

Migration management is often thought of as the domain of national governments. But a group of European cities is highlighting their role in working with irregular migrants, producing guidance and bringing their voices to European-level policy making through the C-MISE exchange.

Something stands out about their work: these local level authorities focus on support and services for people without documents. A stark contrast to the enforcement, deterrence and detention approach increasingly popular among national governments in Europe.

Closer to the realities of irregular migration

Perhaps this isn’t surprising, as cities have competence in ensuring the welfare of residents and are closer to the realities of irregular migration. They witness first-hand the experiences of people without documents who often can’t access basic services and the challenges this brings for individuals, local communities and authorities.

In Athens, Eleni Takou of Human Rights 360 shares “Most people without documents end up in Central Athens, either under the radar or seeking onwards routes. This has meant Athens city has to be proactive – it has a coordination centre for NGOs and other stakeholders, and has been active in providing services and supporting referrals to housing and healthcare.”

Addressing local concerns: approaches that work better

Impoverishment, homelessness, destitution and barriers to social cohesion are some of the challenges cities face, linked with irregularity. People are often detained repeatedly and sometimes for prolonged periods, in violation of EU legislation. And when they are released from detention, with all the problems this brings, cities have to pick up the pieces.

So could collaboration among cities and NGOs provide another way, addressing local concerns while better ensuring rights and resolving cases in the community, without immigration detention?

Jan Braat of the City of Utrecht, who chairs the C-MISE exchange, thinks so: “In the Netherlands, 50% of people [in an irregular situation] end up on the streets – the national government’s approach hasn’t worked. We’ve shown that it’s better to build trust and work with people”.

Building trust, solving cases in Utrecht

Utrecht City partners with NGOs to provide professional guidance and support to people without documents, to reduce irregularity in the city. The programme has achieved case resolution for most its clients: since 2002, 59% of participants received legal status, 19% returned to their countries of origin, 13% re-entered national asylum shelters, and only 8% disengaged.

Rana van den Burg at SNDVU, an implementing NGO, tells us about their approach:

“The key to our support is that it’s based on trust between the contact person and the client. People often believe that their case hasn’t been looked at properly by immigration authorities, increasing distrust in the system and facilitating disengagement from the procedures”.

At SNDVU, a contact person accompanies each individual throughout the migration procedure and ensures they have access to clear and accessible information in order to make difficult decisions. Along with this professional guidance, the programme provides accommodation, pocket money, legal aid and social support so that people can meet their basic needs and actively participate.

Rana explains that “working together with people and having a judgement free attitude, while facilitating their agency and decision-making is the key to resolving cases”. The programme does not impose a time limit for participation, in order to give participants time to explore all options for case resolution. An agreement with the police means clients can’t be detained.

Growing evidence

While this approach is still innovative in Europe, there’s growing evidence that it works. Last year, an in-depth Council of Europe analysis found that trust and support, including individualised case management, are key to effective alternatives to immigration detention (ATD). Evidence from three NGO-run case management pilot projects in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Poland, backs this up.

NGOs are often well placed to implement case management ATD programmes, with expertise in working with one to one migrants and building the rapport necessary foster engagement. And as civil society organisations consider how pilot projects can be scaled up towards systems change, cities stand out as potentially important stakeholders.

Influential stakeholders

Not only do cities have the ability to mobilise services and support networks available in their community, as first responders, they can act as entry points to regional and national governments. Their voices could be influential in changing narratives around migration and detention.

From this year, for example, Utrecht’s professional guidance programme is receiving funding from the Dutch national government. This is part of an agreement with five municipalities which will provide 59 million EUR funding for pilots over three years (in Utrecht, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Eindhoven and Groningen) - and has enabled Utrecht to expand its programme.

It’s significant that with this agreement, the Dutch national government has shifted away from an exclusive focus on returns which it doggedly maintained for years. Could this multi-level collaboration provide a step towards systemic change? For local NGOs, maintaining independent quality case management - which genuinely supports people to explore all options (rather than focusing on return) and make decisions in an informed and dignified way – will be key.

Meanwhile, the European Commission is engaging cities on irregular migration, rightly recognising that national governments can’t do this alone. The C-MISE cities have a refreshing message in this debate: they want to start a conversation acknowledging that EU policies should not disregard the social hardships lived by irregularly staying migrants and that more inclusive responses are needed.

Multi-level collaboration as a route to change

EU policy and national governments are increasingly relying on enforcement and detention to try to achieve migration management goals. But it’s well known that detention is not only harmful and costly, it does not promote case resolution.

In this challenging context, collaboration between cities and NGOs could develop approaches that treat people as human beings, supporting individuals to resolve cases in the community without detention.

For cities, this could provide a way to address local challenges, while informing and influencing national and European policy. For civil society, it could provide the building blocks for systems based on humanity and dignity that work better for everyone.

Shifting the narrative and practice on migration management - from enforcement to engagement - is a multi-level task that requires collective action.