Interview Compiled by Madeleine MacMillan-Perich

Communication Intern, International Detention Coalition (IDC)

As part of my internship, I wanted to contribute to our blog series ‘Change Can Happen,’ which aims to highlight individuals in the community that are driving positive change and drawing attention to issues surrounding immigration and immigration detention. In my research, I came across a couple of Australia-based filmmakers who have put their skillset to use by making socially conscious, activist and documentary films – Bill Irving and James L Brown.

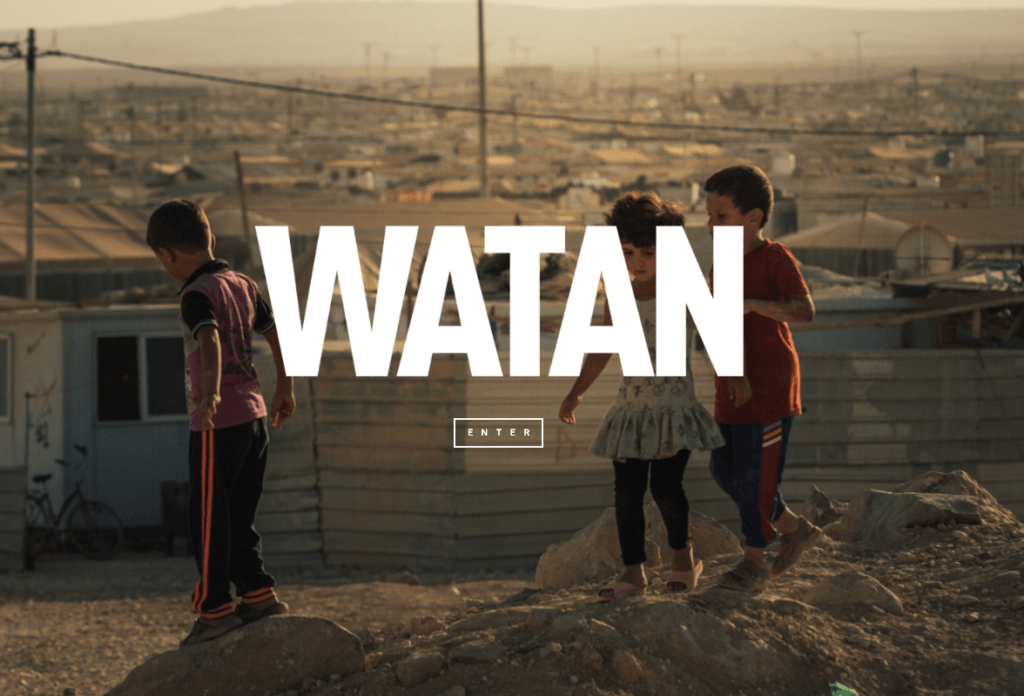

In particular, Bill and James are co-directors of Watan (2018) – a documentary that aims to subvert rhetoric by conducting interviews with people affected by the Syrian refugee crisis – creating a platform for the voiceless and revealing the often-overlooked human cost of the issue.

“Intimate portraits of refugees in the camps and cities of Jordan reveal a very human struggle for normalcy and dignity in a situation that is everything but.”

I was grateful for the opportunity to interview them, and learn more about their craft and passion for social justice:

Tell us a bit about yourselves.

James and I are filmmakers who have known each other since film school in 2004. We work under the moniker Bill and Brown.

Tell us about the projects you have undertaken.

Last year we finished a feature documentary called Watan about Syrian refugees living in camps in Jordan. Next month our short ‘The Year is 2020’ will be released.

What compelled you to pursue this project?

James flew to Jordan solo to shoot the interviews and footage that became Watan. He was motivated by a general disgust with the rhetoric in the Australian ‘debate’ about the global refugee crisis. He wanted to see it for himself.

Why have you chosen to draw attention to the issues of migration and the refugee experience as a focus for your work?

I think it’s a recognition of our good fortune and to have the opportunity to elevate the stories of people who do not. I feel a responsibility to do that.

It’s also an anger and frustration that we feel at the state of the refugee ‘debate’ in Australia. To me it’s horrific that there is even debate. It’s an obligation to settle refugees and asylum seekers. It’s a responsibility, demanded by international law.

I want to be proud of my country. Off-shore detention is so shameful. Not to mention illegal. Future generations will look to this period of Australian history and be disgusted. I want to know that we tried to do something about it.

How did this experience alter or shape your perception of the on-going global refugee crisis and the lives of those affected?

I think the most tragic thing is that James was there in 2016. We made the film and finished it in 2017. We were promoting it in 2018. We have lived life. Done things. Travelled. Worked.

Nearly all of the participants in the film are still right where James shot them.

I think that’s the biggest thing. The crushing actual physical reality of long-term internment. People make the best of a situation, of course they do – life finds a way, and that is kinda nice from a story telling perspective, but this is the only life they have. And it is being taken away from them, while the news cycle forgets about them. While we in the West can turn away. Watch something else. Think about something else.

“The public has refugee fatigue” is a phrase we heard a lot while trying to find a platform for Watan.

That is so unfair it makes your heart break.

What do you hope your audience takes away from your work?

We just hoped that people might be able to picture themselves in the shoes of one or more of the people in the film. Empathy changes everything. It breeds compassion. Refugees are not other people. They are people. Like us. Our policies and sense of responsibility should reflect that understanding.

- For more information about Bill and James visit: https://www.billandbrown.com

- For more information about WATAN visit: https://www.watanfilm.com/