Alternatives to detention in transit migration contexts

In Mexico, just one year after the publication of the General Law on the Rights of Children and Adolescents (2014), IDC promoted a pilot program that saw the release of unaccompanied children and adolescents who were deprived of their liberty in immigration detention centres and their reception and care in community-based civil society programs. In collaboration with the National Migration Institute and the organizations Casa Alianza and Aldeas Infantiles, this experience was pioneering as a strategy to shift perspectives and open possibilities for structural change. It provided evidence to strengthen the advocacy that later, in 2020, enabled legislative reform of the Migration Law to prohibit the detention of children and adolescents for migration-related reasons. This is particularly important considering that Mexico is a country that traditionally receives transit migration.

IDC has found that there is evidence from other countries in the world where they have implemented alternative to detention (ATD) measures aimed at various populations -such as women, families or refugees-, in migration contexts commonly referred to as "transit" or that could be applied in contexts with these characteristics. Regardless of the political category assigned to the migratory context (transit or destination), IDC promotes the adoption of ATD in response to international commitments to move towards ending immigration detention. To this end, IDC acknowledges and promotes the efforts of governments and civil society to build migration governance systems that guarantee dignity and human rights.

"Most critically, immigration detention has detrimental effects on individuals, communities and entire societies."

Why is it important to systematise and share good practices of ATD around the world?

While there has been progress in adopting ATD around the world, immigration detention continues to be a widespread response to international migration, not only in Mexico, but in other countries as well. Disseminating the actions that governments can take in a manner that respects human rights, while strengthening community participation and contributing to transparency and efficiency in the use of public resources, is a task that seeks to inspire stakeholders in charge of protecting the rights of people on the move.

Although there are specific challenges and common questions about the application of ATD in contexts with "transit migration", IDC has worked on research that helps to clarify concepts, myths, arguments and experiences in order to provide useful elements to advance its implementation in these contexts. On the one hand, it allows us to break down some key concepts (such as "transit migration" itself) as well as the factors that encourage the use of immigration detention. In addition, it provides answers to the main questions related to the application of ATDs in contexts with "transit migration" and some considerations on how and when ATDs can be useful as a strategy for those who work in advocacy and design or operation of public policies that prioritise freedom.

To this end, IDC has explored experiences in Australia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Jordan, Libya, Malaysia, Mexico, Poland, Switzerland and Thailand and systematized the most relevant ones.

To learn more:

We invite you to read our publication Alternatives to Immigration Detention in Transit Migration Contexts for more practical examples and recent developments in the field of ATD, in order to highlight promising practices and encourage further progress in this area.

Immigration detention as an exceptional measure of last resort

Since the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the right to personal liberty has been taken up in various international treaties. This right is one of the main frameworks for addressing the arbitrary detention of people on the move.

As part of migration management, governments around the world carry out various actions as part of state policy, one of which is detention.

IDC has documented the various detrimental effects of immigration detention, including the criminalisation of migrants (including those in need of international protection), psychosocial effects on individuals and their communities, human rights violations, as well as high costs to governments.

"Irregular migration is not a choice of the people, but a consequence of the policies and actions of the state.”

Therefore, international standards support the elimination of immigration detention, and one of the strategies to achieve this is to limit its application only as an exceptional measure of last resort. This principle has been taken up in various countries and is enshrined in their legal frameworks; however, there are several challenges in its implementation.

How can the principle of last resort for immigration detention be applied?

In order to ensure that states gradually eliminate and put a complete end to the use of immigration detention, there are some key advocacy actions that can be taken up by legislative actors, public officials or civil society organisations themselves.

Several international instruments prohibit immigration detention for various groups, such as children and adolescents, asylum seekers or people in vulnerable situations, such as pregnant women, nursing mothers, elderly people, people with disabilities, LGBTQI people, or survivors of human trafficking, torture and other serious violent crimes.

In the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, States have committed to prioritise non-custodial alternatives consistent with international law, and to adopt a human rights-based approach to any detention of migrants, where detention is only used as a last resort.

The exceptionality of detention must be based on an individual and context-specific assessment, an analysis of all options, and the decision to opt for detention must be lawful and demonstrate a legitimate aim.

Based on the experiences of its members and partners, IDC set out to compile promising practices in the application of the principle of last resort around the world, including examples of national legislation and its possible effect on the use of detention as an immigration control measure.

Find out more:

We invite you to read our briefing paper – Immigration Detention as an Exceptional Measure of Last Resort – to learn more about the international standards in which the principle of last resort is raised, as well as some promising practices, in order to encourage further progress on this issue.

An interview with IDC's Carolina Gottardo

This interview was first published by the European Programme for Integration and Migration (EPIM)

In this Civil Society Spotlight interview, we hear from Carolina Gottardo, the Executive Director of International Detention Coalition (IDC). Carolina guides the global network of 275+ organisations, individuals, and community members from around the world to advocate for the human rights of those affected by immigration detention. Through strategic collaboration with civil society, UN agencies, and governments at various levels worldwide, IDC works to build movements and shape legal, policy, and procedural changes aimed at reducing and ultimately ending immigration detention and promoting rights-based alternatives globally.

Carolina is a migrant lawyer and economist with over 20 years of human rights experience specialising in migration, asylum, and gender. Carolina has previously held leadership roles at the Jesuit Refugee Service Australia and Latin American Women’s Rights Service, among others.

EPIM has supported IDC’s work with the European Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Network, which brings together NGOs running case management-based alternatives to detention pilot projects in seven European countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Poland, and the UK) with regional-level and international organisations.

1. Can you tell us about IDC’s scope of work and how it has evolved since you started working in the organisation in 2020?

IDC is a global network with members in more than 75 countries that advocates for the rights of migrants, refugees and people seeking asylum, aiming to reduce and ultimately end immigration detention and implement rights-based, non-custodial alternatives to detention.

IDC approaches ATD as a systems change strategy working towards ending immigration detention while building migration governance systems that ensure dignity and human rights for people on the move in the community and out of immigration detention. In partnership with civil society, UN agencies, and multiple levels of government, we strategically build movements, and influence law, policy, and practices, putting the voice of people with lived experience at the centre.

Over the last few years, IDC’s mission has evolved from initially aiming to reduce immigration detention to ending immigration detention. We have also fine-tuned our approach to alternatives to detention as systems change strategy for migration governance systems that do not involve the use of immigration detention.

2. Over the past years leading the European ATD network, can you talk about some of the major wins for the network?

The ATD pilots and initiatives coupled with the advocacy around these at national and regional levels, have resulted in several impactful developments.

These have included: formal government-civil society partnerships established to provide case management based ATD; the development of institutional capacity for ATD in government departments; the establishment of working relationships with government departments and local authorities, the development of evidence-based evaluations on the impact of the ATD pilots, as well as increased awareness and expertise among government institutions, parliamentarians and increased interest and understanding in ATD among local NGOs, academia and the media.

For example, the Association for Legal Intervention (SIP) in Poland signed an MOU with authorities whereby people with specific vulnerabilities who are at risk of detention would be referred to their pilot instead of being put in detention.

In Cyprus, The Cyprus Refugee Council established an unofficial partnership with the national migration department allowing people were released into their ATD pilot. This also later led to the appointment of a dedicated ATD officer.

In Belgium, the Immigration department begun the deployment of Individual Case Management coaches to support undocumented people to resolve their cases in the community with JRS Belgium.

CLA in Bulgaria is working with the national government on ATD programmes and local authorities in Italy, including Rome and Torino, are working closely with CILD, Progetto Diritti and Mosaico on ATD implementation.

3. One of the criticisms we hear about ATD, is that there the political atmosphere currently is not conducive to them – is that true? What then has the work achieved? And is there a future for ATD in Europe?

While the political climate indeed poses challenges for ATD, it is not novel, and the atmosphere has never been straightforward to navigate.

In addition to recent restrictive policies and criminalization trends nationally, the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum is likely to lead to a concerning increase in the detention of migrants, including children and families.

Some governments across the political spectrum recognise that immigration detention is not an effective solution to migration management and does little to support case resolution or deter those hoping to make the journey to Europe. There is evident enthusiasm from some states on ATD, which is clear from the rise in promising practices in European countries and the increased visibility of detention and ATD in a number of international fora. There is also a global momentum on ending child immigration detention that needs to be advanced, and potential opportunities for ATD implementation at national levels despite the forthcoming Pact. Peer learning approaches and the exchange of promising practices have also attracted the attention of states, with some such as Portugal, willing to function as ATD “champions” and connect national, regional, and global efforts.

4. What have IDC and the pilot partners learnt about relationship building over these past years? How does this support advocacy for a long-term end to detention?

Relationship building has been an essential component of the pilots’ success and the effective advocacy of the network.

The development of working relationships and informal agreements with relevant national and local authorities have been successes by themselves and have also led to increased awareness, knowledge and understanding of ATD and some authorities have incorporated and implemented the concept at the government level.

Establishing formal agreements with governments has been particularly important when it comes to scaling up case management-based approaches. The resources required to lead to meaningful and long-term change in migration governance systems are far greater than those that can be provided by civil society alone, and partnerships and multi-stakeholder governance on migration are key to addressing this gap.

In addition to the importance of collaborating with authorities, and seeing the more significant impact it can have, we have learnt that through forming partnerships with like-minded organisations, the Network can extend its advocacy efforts and facilitate change on a larger scale. Expanding partnerships beyond migration-oriented civil society organisations and beyond civil society is important, such as collaborating with local authorities. This can lead to dialogue with policymakers and can allow for case management-based approaches to emerge in other contexts.

5. In terms of migration and integration in Europe today, what change do you see that makes you the most hopeful?

It is challenging to be hopeful when witnessing the increased criminalization of migration and the new Asylum and Migration Pact.

That said, recent regularization programmes like the one in Ireland, or the framing of migration and regularisation in Portugal have been a positive development and recent progress on ATD that focuses on solutions, including government-civil society collaboration are interesting.

The response to the situation in Ukraine has been hopeful, clearly illustrating that coordinated responses, not based on criminalization, could work when there is political will. Additionally, the work of local authorities in different cities across Europe that are championing welcome and integration for people on the move, also gives us hope. Another promising area is joining national, regional, and global efforts and increasing peer learning opportunities to share promising practices.

Other interesting developments include the increased momentum on lived experience leadership and the enhanced solidarity of global civil society working on migration in a more intersectional manner.

6. Knowing what you know now, what would you advise practitioners entering the field today?

After over two decades of working on advocacy issues on human rights, migration, and gender and being a very motivated and idealistic person to begin with, these are my takeaways:

You are there for the long haul. Systemic change does not happen overnight and requires time, tactical approaches, and different actors. Systemic change is not linear either.

Do not lose hope. Sometimes advocacy work could be a thankless effort, particularly in such a politicised issue such as migration. However, migrant rights practitioners and advocates have a key role to play.

Social change is a collective effort requiring multiple actors working at various levels and changing tactics according to different contexts. You cannot achieve change by yourself, but you can put in your grain of sand towards social change and rights-based approaches, and your efforts certainly matter.

The work of civil society is crucial for pursuing change through migration-related advocacy. However, limited funding is one of the main challenges that limits civil society efforts and impact. Additional resources for this work are essential and we need to be creative about fundraising.

Focus on solutions and not only problems. This is an effective way of engaging with decision makers and presenting palatable ways to move ahead. I have found it helpful to go beyond criticism, although denouncing and criticism also have an essential role to play.

-Effective advocacy efforts require different tactics, and there is room for insider and outsider advocacy, lobbying, campaigning, strategic litigation, and movement building. The challenges we face with the criminalization of migration are significant, and these approaches complement each other. Every organization can build on their strengths and work closely with others.

7. What have you unlearned since working with IDC?

To think differently about engagement and to leave stereotypes behind.

I have worked with civil society for over two decades in different countries and contexts. The work with IDC has been one of the most impactful I have been involved with because it is focused on solutions-based approaches.

This implies getting out of traditional ways of thinking and stereotypes and working hand in hand with others, including government officials at various levels and other stakeholders.

Governments are complex entities made of distinct levels and different departments. They do not all think the same, so understanding closely how they operate is critical. Often, as part of civil society, we sometimes oversimplify governments. However, many champions within governments could be allies for the change we want to make. Even if the aspirations are different, common ground could be sought. We need to scale up our efforts and increase our impact. Negative or fixed stereotypes do not help us to achieve this.

One of the most important aspects of working with IDC has been exploring diverse ways of working and thinking outside-the-box. Collaborating with the right allies both within and outside of governments could help us to advance our cause, of course always ensuring that there is no risk of co-option, and that the promotion of migrants’ rights is always at the very heart of all our efforts.

Psychosocial Impacts of Immigration Detention

For decades, civil society organisations and human rights defenders have denounced the poor conditions of immigration detention spaces and how they foster human rights violations against people in contexts of mobility in Mexico and the United States.

In recent years, it has been increasingly recognised how important it is to focus conversations on this issue on affected people themselves, especially on the consequences that deprivation of liberty has on their wellbeing and the various ways in which it affects their mental health and relationship with their environment.

For this reason, IDC promoted research on the psychosocial impacts of immigration detention on people who have been detained or who have been at risk of being deprived of their liberty for immigration reasons in Mexico and/or the United States. The objective of these efforts is to make relevant information available to governments in order to advance the design and implementation of programs and/or public policies aimed at mental health care and the promotion of alternatives to detention.

This work considered the documentary review of other related research or reports, in addition to conducting focus groups with people in mobility contexts in Mexico.

What are the psychosocial impacts of immigration detention?

In Mexico and the United States, immigration detention is used as a generalised measure to deprive people of their liberty while their immigration case is being resolved, which in itself has a negative impact. Especially in Mexico, detention is usually made invisible when it is shielded by the use of euphemisms such as presentación ("presentation") or alojamiento ("housing"). This deprivation of liberty is accompanied by other immigration containment measures, such as roadblocks, greater restrictions or requirements for entry, militarised responses and criminalisation, among others.

Research shows that both people who have been detained as well as those who are or were at risk of being detained may face similar impacts. This is because the possibility of being detained by the authorities means that people are forced to take more dangerous routes, are exposed to risky behaviours that facilitate their entry across borders and are more vulnerable to criminal actors.

Psychosocial impacts have two dimensions, one individual and the other community. On an individual level, people may experience fear, anguish, uncertainty and worry, which is expressed in sleeping difficulties, sadness and hopelessness. It is worth mentioning that, even after release, fear persists in the face of the possibility of being detained again.

On the other hand, at the community level, the consequences of detention have an impact on families and communities, both those of origin and those of destination. Anguish and uncertainty are also effects that the families of detained persons may experience, especially when they have limited information about the situation of their family member or little certainty about what is going to happen.

From the focus groups, we learned of cases in which the effects and damage to mental and emotional health continued after people were released, in addition to the fact that the time factor was not necessarily proportional to the effects – i.e., a person who was in detention for a week can present the same effects as someone who was detained for months.

Finally, our research also showed how damage can occur in adolescents who remain in a shelter or social assistance centre when the models of these spaces do not allow exits (closed-door models), and in effect, the adolescents are deprived of their freedom.

"I did not process what I went through until I got out of there."

"My body could no longer resist, I became anxious."

"I am so afraid of being caught again."

– Phrases from focus group participants.

What role do Alternatives to Detention (ATD) play in counteracting these effects?

Alternatives to detention are synonymous with freedom. According to international treaties on the subject, immigration detention should be exceptional and be used as a measure of last resort, so we call on States to apply alternative measures that guarantee the freedom of people in contexts of mobility.

When people have access to an alternative measure in the community, not only do they avoid the effects of deprivation of liberty, but they are also freed from the human rights violations that usually occur in places of detention. At the same time, the evidence that IDC has through its work with ATD shows that these measures contribute to people's confidence in their administrative and/or legal processes, translate into the follow-up of their actions (i.e., they do not abandon their procedures) and facilitate their integration into the host communities, as they are certain of their options and what they can expect for themselves and their families.

To learn more:

We invite you to read our publication Alternatives to Immigration Detention in Transit Migration Contexts for more practical examples and recent developments in the field of ATDs to highlight promising practices and encourage further progress in this area.

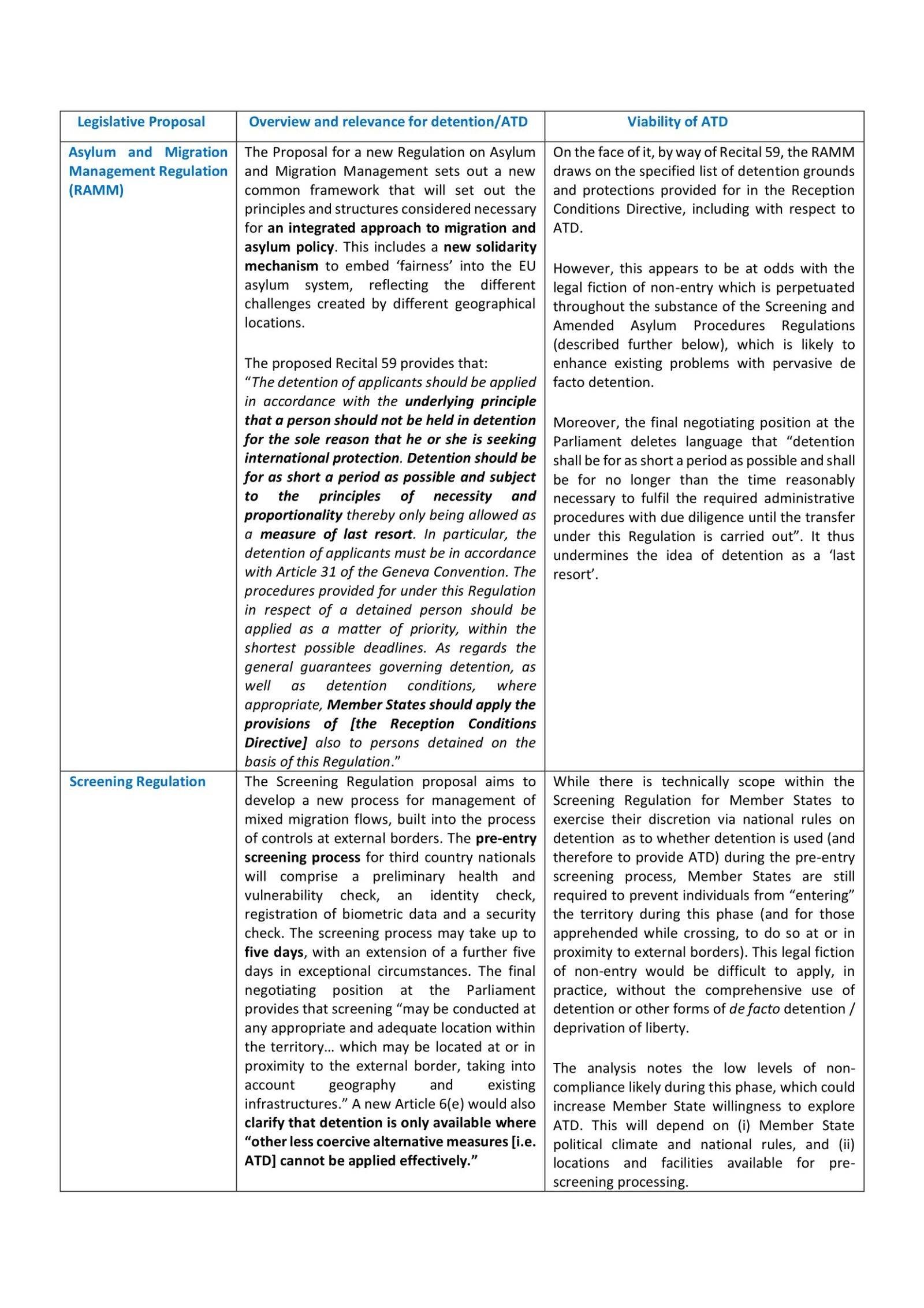

Alternatives as fiction? What the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum means for Alternatives to Detention

In June, EU Ministers responsible for Justice and Home Affairs met in Luxembourg to discuss, amongst other issues, reform of the EU’s approach to asylum and migration. Their discussions resulted in an agreement on two key files – the asylum and migration management regulation and the asylum procedure regulation. Almost three years since the European Commission published its proposal for a New Pact on Migration and Asylum, progress on moving forward the proposals contained within the Pact has been uneven. Following lengthy discussions within the European Parliament, a Roadmap published by the co-legislators in September 2022 set out their joint commitment to adopt the legislative proposals within the Pact before the end of the 2019-2024 legislative period. Sweden, which held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union from January to June 2023, expressed its intention to “advance the negotiations on a Pact on Migration and Asylum.” It now looks like an agreement may be in sight.

In recent months, Linklaters LLP and International Detention Coalition (IDC) undertook an analysis of the provisions laid out within the Pact in order for IDC to better understand the implications when it comes to the viability of alternatives to immigration detention (ATD), should the provisions outlined be agreed upon and implemented. Given the recent movement made on the Pact, we set out below IDC’s summary of findings based on that legal analysis, in order to shed light on the consequences of the Pact for the continued viability of ATD in the EU. You can access the original research report undertaken by Linklaters LLP for IDC here.

Detention in the Pact proposals

The effect that the Pact is likely to have on the use of detention in the EU is already well-documented. The International Commission of Jurists has pointed out that “prolonged immigration detention will inevitably result as a practice”, and the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants has concluded that the proposals set out within the Pact will result in “more detention, fewer safeguards.”

Detention within the Pact is largely set out within the Screening Regulation and the Amended Asylum Procedures Regulation. These two instruments outline a new screening process for individuals at external borders and establish border procedures for processing asylum applications and facilitating returns.

The European Commission itself has affirmed that border procedures “imply detention.” The new Pact proposals therefore undermine the principle that detention should only be applied as a measure of last resort; instead, depriving people of their liberty at the borders is set to become the default approach.

For those who are refused asylum, the border procedure may mean being detained for up to 6 months at the EU’s borders and, in exceptional situations, procedures can be extended – meaning that people may spend up to 10 months in detention at the border.

The proposed changes serve to deny people full access to their rights by creating a situation whereby they are not considered to have legally ‘arrived’ in an EU Member State despite being physically present on the territory – a practice dubbed the ‘fiction of non-entry’. Moreover, the proposed border procedures will likely apply to children aged 12-18, meaning that children will also be detained. This is in direct conflict with the commitment set out within the Global Compact for Migration (GCM) – signed by the majority of EU Member States – to work towards ending immigration detention of children.

These proposals are not without their critics, and indeed have been sticking points during the long negotiations in the European Parliament. During an early debate in Parliament, MEPs raised concerns around border procedures and in particular pointed to the likelihood that border procedures would resemble policies implemented in Greece that have led to widespread deprivation of liberty or de facto detention.

Viability of ATD within the Pact proposals

The table below outlines the key aspects of the proposed legislative instruments contained in the Pact (as of June 2023) which are of relevance to the viability of ATD.

Whilst the Pact’s legislative instruments do not expressly refer to ‘alternatives to detention’, some references are made to ‘less coercive’ and ‘less coercive alternative’ measures. This reflects existing language in the Return Directive and Reception Conditions Directive. Moreover, it is implied that immigration detention will continue to be used only as a last resort, in line with regional and international legal standards, and that alternatives will be considered before detention.

Whilst the Pact’s legislative instruments do not expressly refer to ‘alternatives to detention’, some references are made to ‘less coercive’ and ‘less coercive alternative’ measures. This reflects existing language in the Return Directive and Reception Conditions Directive. Moreover, it is implied that immigration detention will continue to be used only as a last resort, in line with regional and international legal standards, and that alternatives will be considered before detention.

However, despite this intention it is difficult to see how the provisions of the Pact – as currently drafted – would allow for community-based ATD in practice.

It is particularly difficult to envisage how Member States will be able to implement ATD while ensuring the “fiction of non-entry” is upheld – after all, how can states place migrants within the community if they do not acknowledge their legal presence in the country? ATD will be particularly challenging if other Member States follow the approaches already being taken in Greece (given apparent similarities between Greek national law and the Pact), Italy and Spain, where border procedures have resulted in de facto detention as standard. Indeed, according to the European Parliament Research Services Study on the Pact:

“the blanket non-entry policies for all migrants (during screening, thus including refugees), or particular categories of migrants (in case of the mandatory border procedure or for rejected asylum seekers in the return border procedure), makes it impossible to ensure compliance with the guarantees in the Reception Conditions Directive and the Return Directive.”

Simply put, the fact that an individual can physically arrive in a country without being considered to have legally arrived, will inevitably result in considerable restrictions on freedom of movement and access to services – and this deprivation of liberty is at odds with the idea of ATD.

Ensuring meaningful alternatives to immigration detention

Enshrining ATD in legislation and policy provides an important safeguard against the use of detention. At present, EU Member States can only detain migrants if effective alternatives are not available – this serves to ensure that governments are not detaining individuals in a manner that is arbitrary, unnecessary and disproportionate.

Yet in the current framework of the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum, which by its very nature is likely to introduce widespread and indiscriminate detention of people in the context of expanded border procedures, it is difficult to see how such procedures will function without resorting to de facto detention. In this context, legal requirements to use ATD will be unlikely to work in practice.

With the Council position on the Pact now clear, trilogue negotiations are beginning in earnest as the co-legislators aim to reach a conclusion by early 2024. It is vital that the negotiations keep existing regional and international legal standards front and centre, particularly when it comes to the right to liberty. In order to do this, ATD must be included as a meaningful way to ensure that immigration detention is only ever a last resort, with concrete possibilities for community-based ATD identified.

Our analysis shows that this will be challenging, but the alternative – large-scale, de facto detention at the borders for extended periods of time – is unthinkable.

OCC & ECDN Call on Malaysian Government to Release Children from Immigration Detention & Implement ATD

Versi Bahasa Melayu di bawah

PRESS STATEMENT

Sydney, 20 June 2023- On World Refugee Day, the Office of Children Commissioner (OCC) and the End Child Detention Network (ECDN) join hands to urge the Malaysian government to take immediate action towards ending the detention of children in immigration facilities and implementing effective Alternatives to Detention (ATD).

It is deeply concerning that as of 15 May, 11,068 people including 969 children, including refugee children, are held in immigration detention in Malaysia. These children have fled violence, conflict, and persecution in their home countries, seeking safety and protection in our nation. It is our moral obligation to ensure their well-being and safeguard their rights.

We call upon the Malaysian government to embark on the following crucial steps:

- Begin releasing children from immigration detention into an Alternative to Detention (ATD) program, and ensure the inclusion of all children, regardless of their migration status.

- Ensure that ATD projects are implemented in good faith to achieve its primary objective, which is to resolve the issue of arrest and detention of children.

- Urgently present the working paper on shifting children out of immigration detention depots in Cabinet, a vital document currently being developed by the Home Ministry.

- Develop a comprehensive legal framework for refugees that grants them legal status and access to employment, health services, education, and social, and public benefits. This framework is crucial in protecting refugee children and building an environment for their healthy development.

- Grant United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) unrestricted access to immigration detention centres. This will allow for the continued registration of persons of concern and the subsequent release of all individuals registered with UNHCR, facilitating their integration into the community.

- Take immediate steps to enact legal and policy changes to halt the immigration detention of children, including all refugee and asylum-seeking children.

- Conduct a comprehensive review of immigration detention policies and practices to ensure they align with international legal and human rights standards. This review is imperative to safeguard the rights and well-being of all individuals at risk of immigration detention, particularly children.

By taking these significant steps, Malaysia will not only fulfil its international obligations but demonstrate its commitment to protecting the rights and dignity of every child, regardless of their migration status. We firmly believe that these measures will bring us closer to a society that respects human rights, embraces diversity, and upholds the principles of compassion and justice.

As OCC and ECDN, we stand ready to collaborate with the Malaysian government and other stakeholders to develop and implement effective ATD solutions that prioritise the best interests of all children in Malaysia, including refugee and asylum-seeking children.

Together, let us work towards a future where no child is subjected to the harmful impacts of immigration detention, and where every child can thrive and realise their full potential.

About OCC: The Office of Children’s Commissioner (OCC) is an independent office within the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, tasked with promoting and protecting the human rights of all children in Malaysia.

About ECDN: The End Child Detention Network is a coalition of 21 civil society organisations and individuals working to ensure that no child is detained in Malaysia due to their immigration status.

For more information, please contact: Hannah Jambunathan - End Child Detention Network (ECDN) Coordinator & Asia Pacific Programme Officer, International Detention Coalition, [email protected]

KENYATAAN MEDIA

OCC dan ECDN Menyeru Kerajaan Malaysia untuk Membebaskan Kanak-kanak daripada Tahanan Imigresen dan Melaksanakan Alternatif kepada Penahanan

Sydney, 20 Jun 2023- Pada Hari Pelarian Sedunia, Pejabat Pesuruhjaya Kanak-kanak (OCC) dan Rangkaian Penghapusan Tahanan Kanak-Kanak Malaysia (End Child Detention Network - ECDN) berganding bahu untuk menggesa kerajaan Malaysia mengambil tindakan segera ke arah menamatkan penahanan kanak-kanak di depot imigresen dan melaksanakan Alternatif kepada Penahanan (ATD) yang berkesan.

Angka yang membimbangkan setakat 15 Mei 2023 iaitu sebanyak 11,068 individu termasuk 969 kanak-kanak, termasuk kanak-kanak pelarian ditahan dalam tahanan imigresen di Malaysia. Kanak-kanak ini telah melarikan daripada keganasan, konflik, dan penindasan di negara asal mereka, dan mencari keselamatan dan perlindungan di negara kita. Adalah menjadi kewajipan moral kita untuk memastikan kesejahteraan mereka dan menjaga hak mereka.

Kami menyeru Kerajaan Malaysia untuk melaksanakan langkah penting seperti berikut:

- Memulakan proses untuk mengeluarkan kanak-kanak dari tahanan imigresen kepada program Alternatif kepada Penahanan (ATD), dan memastikan semua kanak-kanak, tanpa mengira status migrasi mereka dimasukkan ke dalam program tersebut.

- Memastikan bahawa program ATD dilaksanakan dengan bersungguh-sungguh untuk mencapai objektif utamanya, iaitu menyelesaikan isu penangkapan dan penahanan kanak-kanak.

- Membentangkan dengan segera di Kabinet kertas kerja berhubung pemindahan keluar kanak-kanak dari depot tahanan imigresen, yang merupakan dokumen penting yang sedang dibangunkan oleh Kementerian Dalam Negeri.

- Membangunkan sebuah rangka kerja undang-undang yang komprehensif bagi pelarian untuk memberikan pelarian status sah dari segi undang-undang dan akses kepada pekerjaan, perkhidmatan kesihatan, pendidikan, dan faedah sosial dan awam. Rangka kerja ini penting dalam melindungi kanak-kanak pelarian dan membina satu persekitaran yang menyokong perkembangan mereka dengan sihat.

- Memberikan akses tanpa had kepada Pesuruhjaya Tinggi Bangsa-Bangsa Bersatu untuk Pelarian (UNHCR) untuk masuk ke pusat tahanan imigresen. Hal ini akan membolehkan pendaftaran berterusan individu yang terkesan dan pembebasan seterusnya semua individu yang berdaftar dengan UNHCR, yang akan memudahkan integrasi mereka ke dalam komuniti.

- Mengambil tindakan segera untuk menggubal pindaan undang-undang dan polisi untuk menghentikan penahanan imigresen terhadap kanak-kanak, termasuk semua kanak-kanak pelarian dan pencari suaka.

- Menjalankan semakan menyeluruh ke atas polisi dan amalan penahanan imigresen untuk memastikan perkara tersebut sejajar dengan piawaian undang-undang dan hak asasi manusia antarabangsa. Semakan ini adalah penting untuk melindungi hak dan kesejahteraan semua individu yang berisiko ditahan imigresen, terutamanya kanak-kanak.

Dengan mengambil langkah penting ini, Malaysia bukan sahaja akan memenuhi kewajipan antarabangsa Malaysia, tetapi juga menunjukkan komitmen Malaysia untuk melindungi hak dan maruah setiap kanak-kanak, tanpa mengira status migrasi mereka. Kami amat percaya bahawa langkah-langkah ini dapat membawa kita menjadi negara yang menghormati hak asasi manusia, menerima kepelbagaian, dan menegakkan prinsip belas kasihan dan keadilan.

OCC dan ECDN bersedia untuk bekerjasama dengan kerajaan Malaysia dan pihak berkepentingan yang lain untuk membangunkan dan melaksanakan penyelesaian ATD yang berkesan, yang mengutamakan kepentingan terbaik semua kanak-kanak di Malaysia, termasuk kanak-kanak pelarian dan pencari suaka.

Marilah kita bersama-sama berusaha ke arah masa depan yang tiada kanak-kanak terdedah kepada akibat buruk daripada penahanan imigresen, serta semua kanak-kanak boleh berkembang maju dan merealisasikan potensi penuh mereka.

Mengenai OCC: Pejabat Pesuruhjaya Kanak-kanak merupakan sebuah pejabat bebas di Suruhanjaya Hak Asasi Manusia Malaysia yang bertanggungjawab dalam mempromosi dan melindungi hak asasi kanak-kanak di Malaysia.

Mengenai ECDN: Rangkaian Penghapusan Tahanan Kanak-Kanak Malaysia (ECDN) adalah gabungan 21 organisasi masyarakat sivil dan individu yang bekerja secara kolektif untuk memastikan tiada kanak-kanak ditahan di Malaysia kerana status imigresen mereka.

Untuk maklumat lanjut, sila hubungi: Hannah Jambunathan - Koordinator, Rangkaian Penghapusan Tahanan Kanak-Kanak Malaysia (ECDN) & Pegawai Program Asia Pacific, International Detention Coalition, [email protected]

Peer Learning: A Methodology Towards Sustaining & Scaling Up Promising Migration Governance Practices

Written by Silvia Gomez, IDC Global Advocacy Coordinator

Since its inception, IDC has prioritised supporting the development of communities of practice using peer learning as a methodology that facilitates the sharing of ideas, experiences, knowledge, and challenges towards developing, sustaining and scaling up alternatives to immigration detention.

Through more than a decade of sustained collaboration with government actors, civil society organisations, IDC members and the UN, IDC has witnessed how peer learning supports change, accelerates progress, and consolidates rights-based solutions to complex migration governance challenges, as well as encourages ongoing support among stakeholders.

As a global coalition, IDC supports and facilitates several peer learning platforms on alternatives to detention at local, national and regional levels, as well as cross-regional and global levels. The success of this methodology in supporting government actors at different levels has led to consolidating peer learning as a methodology of work in several fora, including as part of the global architecture on migration. The IMRF Progress Declaration, agreed upon by the UN General Assembly in 2022, includes peer learning as one of the key lines of work to advance implementation of the Global Compact for Migration (GCM) (see paragraph 72).

IDC’s History of Peer Learning at the Global Level

In the aftermath of the adoption of the GCM in 2018, IDC, in collaboration with UNICEF, started exploring and testing with a group of champion States and stakeholders how a cross-regional peer learning platform could support in accelerating change and progress in ending child immigration detention at the national level. The 2020 UN Secretary General Report on Implementation of the GCM highlighted this pioneering initiative (see paragraph 48).

Partially as a result of this process, and since 2020, the UN Network on Migration, through its Work Stream on Alternatives to Detention, co-led by IDC, UNHCR and UNICEF, has hosted 3 global peer learning exchanges in collaboration with the governments of Portugal, Thailand, Colombia, Ghana, and Nigeria. These exchanges, held under Chatham House rules, have been attended by 36 governments across regions and gathered representatives from the relevant technical and decision-making departments (see further information in the reports of the global peer learning exchanges). With a clear focus on national level change, and under the leadership of IDC, the Work Stream has also facilitated peer learning discussions to showcase how successful collaboration between governments and civil society on the ground looks like.

IDC has been able to observe how peer learning helps to:

- increase States’ confidence to discuss approaches towards migration governance without immigration detention and to work on alternatives to detention by showcasing promising and best practice, sharing challenges and learnings, co-creating solutions and identifying opportunities for change and progress

- create multi-stakeholder dialogue in a space of trust between governments, local authorities, civil society, UN actors, IDC members, grassroots and experts with lived experience (whole of society)

- support government structures in connecting relevant technical and decision-making governmental departments and actors (whole of government)

- identify areas where specific support and collaboration are needed, as well as opportunities for capacity building, training, and site visits

- foster partnerships, develop a community of practice and build a global network of experts and practitioners

- create further peer learning discussions among specific countries with similar interests at regional or cross-regional level

IDC’s History of Peer Learning at the Regional Level

In Asia Pacific, IDC co-leads the Regional Peer Learning Platform and Program of Learning and Action alongside the Centre for Policy Development (CPD). This Peer Learning Platform was first proposed at the seventh meeting of the Asian Dialogue on Forced Migration (ADFM) in Bangkok in November 2018, where participants identified a regional grouping on this issue as being beneficial to advancing practical progress towards alternatives to detention in the region. Since then, a number of peer learning events, both in person and online have been convened on the topic. Participants are drawn from policy and implementing agencies within the governments of Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand and Thailand, as well as key civil society actors and international organisations. The Regional Platform has been operating from 2022 and last met in October in Kuala Lumpur. The feedback about the Regional Platform has been very positive including: “There is no perfect country but we can all learn from each other” and “It’s been eye-opening and exciting to see what’s been going on in other countries.To see how we are all rising to prioritise this issue."

In the Americas, IDC successfully facilitates peer learning exchanges among local authorities working to end child immigration detention in Mexico, and in August 2022 IDC connected some local authorities that were not previously connected. In the MENA region, IDC facilitated a peer learning workshop alongside UNICEF MENA engaging government actors from relevant technical and decision-making departments from Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Sudan.

IDC is currently developing in partnership with the Uppsala University and with the support from the World Health Organisation (WHO) a peer learning platform between host, transit and countries of origin across Europe, the Middle East and North Africa and the Horn of Africa/East Africa. Such a platform would be an opportunity for countries across different regions to come together to share experiences, challenges and good practice. The forum will aim to build cross-regional trust, cooperation and synergies when it comes to addressing migration challenges on shared routes, facilitating collective problem solving and testing new approaches.

Moving Forward

IDC, alongside our members and partners, will continue to connect local, national, regional and global agendas and actors by integrating the learnings from the above initiatives at local, regional, cross-regional and global level. In doing so, IDC will continue facilitating and coordinating strategic peer learning spaces, centering the leadership of people with lived experience of detention in all of our efforts working towards migration governance systems without immigration detention.

In particular, the recently launched UN Network on Migration Workplan 2022-2024 already includes plans for three upcoming peer learning exchanges (see Work Stream on Alternatives to Detention workplan activities, page 14) - the first, on 24 May 2023, will focus on ending child immigration detention, later this year on alternatives to detention in transit settings, and early next year on prevention of pre-entry detention of migrants.

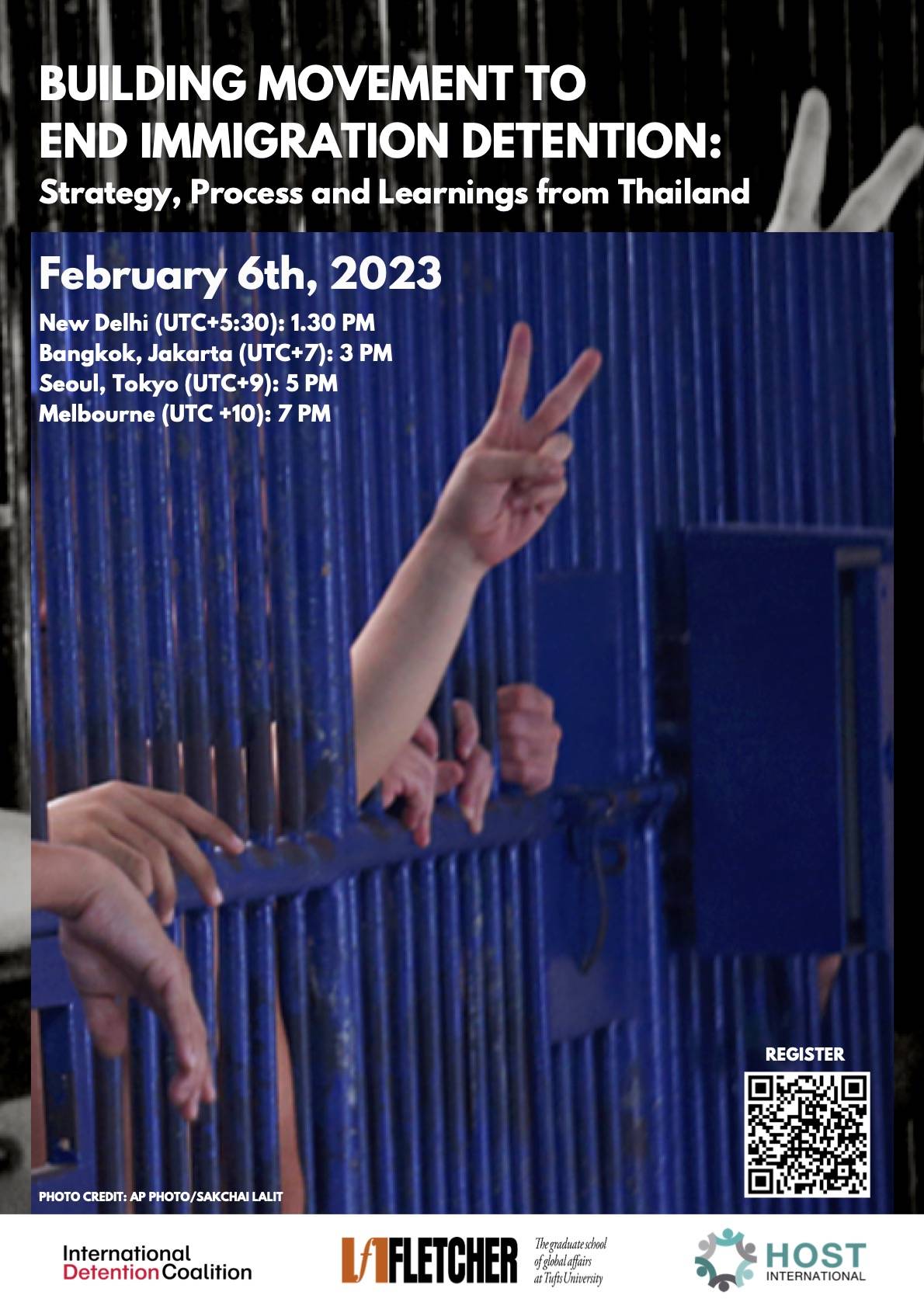

Building Movement to End Immigration Detention: Strategy, Process & Learnings from Thailand

Written by Chawaratt (Mic) Chawarangkul, IDC Southeast Asia Programme Manager

On 6th February 2023, International Detention Coalition (IDC), HOST International, and Fletcher School of Global Affairs International Law Practicum, at Tufts University, co-convened a webinar on Building a Movement to End Immigration Detention: Strategy, Process and Learnings from Thailand.

The use of immigration detention remains prevalent in the Asia Pacific region. It is used in many countries in an arbitrary and discriminatory manner, and without necessary safeguards such as legal limits on the period of detention and guarantee of a person’s procedural right to challenge immigration detention decisions. Migrant children and other migrants in vulnerable situations, such as pregnant women, older persons, persons with disabilities, LGBTQI+ individuals and stateless persons, continue to be held in immigration detention across the region. At the same time, promising practices like alternatives to immigration detention (ATD) are emerging in the region, especially for children, and there is momentum in some countries for reducing and taking steps toward ending child immigration detention specifically.

Thailand is one such country where ATD has emerged as a promising practice. Thailand is situated in the centre of Mainland Southeast Asia and has a long history as both a regional hub for migration and as a host to refugee communities. Due in part to the strength of its economy, Thailand has historically been an important destination for migrants, hosting an estimated 4.9 million non-Thai residents in 2018, up from 3.7 million in 2014.

Prior to 2016, Thailand had a record of detaining thousands of refugee and migrant children annually. However, Thailand has since emerged as a regional and global champion on ATD for children. It has taken important and concrete steps toward ending immigration detention for children and expanding ATD to other migrants in vulnerable situations.

The webinar allowed ATD practitioners and partners in the region to explore some of the key factors that led to these key changes in Thailand. We provided an overview of historical events and unpacked some of the strategies and ways in which civil society, Thailand’s representatives to the Asia Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights, the Thai National Human Rights Commission, UN agencies, academics, the diplomat community, and other stakeholders collaborated to put child immigration detention and ATD on the reform agenda.

The webinar also sought to identify some of the elements that make this movement effective, drawing lessons from the extensive expertise of civil society in Thailand, and give participants space for seeking ideas from civil society in Thailand and reflect on how learnings from Thailand can be applied in other contexts within the Asia Pacific region.

The webinar drew heavily from a report prepared by the Fletcher School of Global Affairs International Law Practicum, entitled ‘Best Interest of the Child: Ending Immigration Detention of Children in Thailand’ which was submitted to the United Nations Special Representative to the Secretary General on Violence Against Children. The report, completed in May 2022, documented how stakeholders, within Thailand and globally, collaborated to build a movement to end immigration detention beginning with children as a gateway to expanding ATD for other migrants in vulnerable situations.

Key learnings from the webinar

- Change takes time, but it is possible and requires long-term strategy and long-term investment;

- While the movement is at the national level, it is critical to connect national, regional and global efforts. Based on the case in Thailand, this multi-level collaboration enhanced change on the ground;

- Multi-stakeholder approaches require skilled coordination, and a joint and clear agenda and theory of change;

- Decision-makers can be more open to engagement when advocacy is solutions-focused;

- A whole of government and a whole of society approach can pave the way to collaborative resolutions.

- Local actors are key to affecting change and must be the advocacy leaders

- ‘One size doesn’t fit all’; however, it’s important to find examples that can inspire lessons for how initiatives can be localised.

Mexican Organisations Look to the Supreme Court to Set Precedent for Non-Detention

Written by Diana Martinez, IDC Americas Programme Officer

Immigration detention in Mexico is one of the most serious problems that non-nationals encounter when entering the country without documents or when their status is irregular. For decades, such detention has been condemned on various levels by human rights organisations. Nevertheless, according to information published by the Unit for Migration Policy, Registration and Personal Identity, the detention of people with irregular status has increased considerably in Mexico over the past decade, from 88,506 in 2012 to 444,439 in 2022, with five times more people apprehended by the immigration authorities.

International, regional, and national human rights organisations have emitted various recommendations to the Mexican government for the modification of immigration policy that would only allow for the use of migrant detention in exceptional cases, in favour of a more generalised use of alternatives to detention. The most significant change thus far has been the prohibition of migrant detention for children and adolescents, as reflected in the 2020 immigration law.

In addition to advocacy by civil society organisations to limit immigration detention, various cases have been taken to the courts, on the basis of violations of due process, the use of arbitrary detention, solitary confinement, and the lack of access to asylum rights, among others. These cases have been accompanied by organisations, private lawyers, as well as the federal public defender.

Currently, two cases are awaiting resolution by the Supreme Court, supported by a close ally of IDC in Mexico, the Alaide Foppa Legal Clinic for Refugees from the Iberoamericana University. Given the negative impact of detention on migrant communities, as well as its importance for the public agenda, IDC contributed to Amicus Curiae in matters of detention and alternatives to detention that were presented to support the resolution of these cases.

These Amicus Curiae, technical documents for ministers of the court, contain specialised information or legal opinions regarding the issue of detention in other countries where the right to freedom is prioritised, as well as examples of the effectiveness of alternatives to detention.

The first Amicus Curiae was presented by the Grupo de Acción por la No Detención de Personas Refugiadas, a network of organisations, jointly headed up by IDC and Asylum Access Mexico, that promotes the elimination of detention for people in need of international protection. Based on findings from recent studies undertaken by IDC, the technical reports provided the court with successful experiences of the use of alternatives to detention, including in countries which, like Mexico, are considered to be transit countries.

The second Amicus was written by IDC, together with the Consejo Global de Litigio Estratégico para los Derechos de los Refugiados, comprising a group of law specialists, defenders, and academics with experience in International law regarding the rights of refugees, forced migration, and the right to nationality. This document presented a legal opinion, based on international standards, on the exceptionality of detention and global trends towards rights-based alternatives.

Through these interventions, IDC, together with our members and allies seek to contribute to changes that will significantly impact the lives of migrant people. In the upcoming weeks, the Supreme Court, the highest constitutional court in the country, will once again have the opportunity to find in favor of due process and the freedom of the migrant population.

Prior to the publication of this blog, the First District Court of the Supreme Court resolved one of the cases favourably by establishing that, independently of the duration of an immigration administrative procedure, the holding of foreign nationals in detention centres should not exceed 36 hours from the time they are first detained, as established in the Mexican Constitution for administrative offences. The First District Court determined that once this period has elapsed, those subject to immigration procedures should continue these while free.

April 2023 Updates: IDC’s MENA Regional Programme

IDC would like to extend its heartfelt condolences to Turkey and Syria following the devastating earthquake in February 2023, that claimed the lives of thousands of people in both countries and affected the whole region.

April 2023 Updates: IDC’s MENA Regional Programme

Written by Asma Nairi, IDC MENA Regional Coordinator

Ending 2022 with a successful regional event

IDC and UNICEF organised a 3-day workshop on "MENA Regional Children on the Move Cross Border Continuum of Protection and Care" in Amman, Jordan in November 2022. 8 government delegations from the MENA region attended, in addition to regional representatives of IOM and UNHCR, and representatives of the governments of Turkey and Catalonia, Spain.

The workshop was a result of a year-long collaboration between UNICEF and IDC to implement a regional project on the protection of refugee and migrant children. Two policy briefs were introduced, one focusing on Whole-of-Government and Whole-of-Society Approaches, highlighting its critical role in supporting children on the move by providing promising practices from the region; and the other on Community and Family Based Alternative Care Initiatives, which highlights the benefits of supporting policies and programs for refugee and migrant children to live in community settings, while their migration matters are being resolved. The policy brief aimed to highlight promising practices and opportunities and included specific examples of informal alternative care arrangements in the MENA region. The workshop was a successful step towards enhancing awareness and collaborative work with governments in the region towards increasing the protection of children on the move.

16 Days of Activism - Webinar on violence against women and girls in detention

In the frame of the 16 days of activism, IDC MENA participated in a webinar coordinated by MADAR network (The Maghreb Action on Displacement and Rights) in December 2022, along with other civil society organisations. IDC focused on the experience of migrant women and girls in detention, and their protection needs and concerns.

IDC highlighted the essential role of civil society in protecting migrant women and girls from violence, including sharing examples from other organisations working on the protection of migrant women. IDC provided detailed recommendations to support women, including conducting research, raising awareness, advocating for measures to end discrimination and exploitation, developing gender-responsive policies, providing gender-specific services (including health and reproductive care), and ensuring access to information during the migration journey in their preferred languages.

An interview with the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) Libya

IDC aims to highlight the critical and important work that our partners and members are doing in the region to advocate for migrant and refugee rights, and end immigration detention. In this newsletter, we feature an interview with one of the organisations working in Libya, and the broader region.

OMCT is the largest global NGO taking a stand against torture while protecting human rights defenders worldwide with over 200 members in 90 countries. In Libya, OMCT works on human rights issues faced by migrants, refugees, and people seeking asylum in official and unofficial detention centres. OMCT has been working in collaboration with local civil society organisations to document these violations, report them to the relevant international bodies, and provide them with legal support.

The Libya project, which founded the Libyan Anti-Torture Network (LAN) in 2021, is one of OMCT’s most prominent projects working on the documentation of grave human rights violations, including inhumane detention conditions of migrants, refugees and people seeking asylum, as well as on advocacy at the global level. LAN brings together a group of civil society organisations from across Libya, which OMCT supports by building their technical and organisational capacities to better address challenges faced by communities on the ground in Libya.

Main Challenges in Libya

- Domestic Libyan legal framework criminalises irregular migration and does not provide humanitarian safeguards for people seeking asylum and people in fear of prosecution in their countries of origin.

- Political and military instability in Libya greatly impacts the lives of migrants and refugees, and their access to justice.

- Access to some detention facilities and prisons is limited, thus documentation and monitoring of the situation becomes extremely challenging.

- Armed groups affiliated to official entities are involved in human trafficking networks, resulting in the spread of torture, sexual exploitation and smuggling.

Opportunities

Capacity building programs are vital as they help improve the understanding of documentation and advocacy at the international level.

- Education and promotion of human rights will help Libyan civil society in building a more peaceful and safe society.

- Advocating for domestic legal reform in compliance with International humanitarian law (IHL) and International human rights law (IHRL) will enforce respect for human rights in Libya, and better fight impunity.

Key Highlights and Achievements

- The Libyan Anti-Torture Network was created with the aim of documenting and highlighting torture, arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, unlawful killings and other serious human rights violations committed against Libyans and migrants inside and outside of detention through targeted advocacy activities.

- The joint thematic report of the OMCT and the LAN published in 2022 titled “That was the last time I saw my brother” is the first report focusing on extrajudicial and unlawful killings in Libya.

- The LAN and OMCT regularly issue statements on the detention of migrants in Libya, including: Rebranded governmental approach, unchanged inhuman practices, New patterns of human rights violations and absence of accountability, and Head of government recognises inhumane detention conditions of migrants