IDC Calls for Releases & Moratoriums Along With US & Mexico Members

The United States and Mexico have for decades been the primary detaining countries in the Americas region, with the largest detention centers and the most sophisticated immigration control and deportation systems. It is estimated that the United States has close to 40,000 people currently in immigration detention and Mexico around 2,000. Against a background of the increasing use of detention, and of particular concern, the continued detention of children, the threat of Covid-19 and a global movement of social distancing highlights the extreme vulnerability of people in immigration detention to the spread of infectious disease, as well as the lack of access to adequate medical care, over and above the rights violations implicit in a system of mandatory immigration detention.

Advocates in Mexico have rallied together around this issues, with a powerful collective of IDC Americas member and partner organizations initiating a multi-level advocacy strategy to demand that the Mexican government release migrants from detention centers due to the risk of contagion of Covid-19 due to the conditions in which people are deprived of liberty.

Together with Instituto para las Mujeres en la Migración, Sin Fronteras, Fundación para la Justicia y el Estado de Derecho, Asylum Access, Otros Dreams en Acción, and other partners, we launched a campaign calling on the Mexican government to release all migrants and asylum seekers from detention centers and provide them with immigration documentation in the form of a temporary humanitarian visa, temporarily suspend migrant raids and enforcement measures throughout the country to avoid new detentions and to provide information regarding the national measures being taken to avoid the spread of Covid-19 and contact information for local health clinics, international and national organizations.

Collective litigation and advocacy work

Throughout these last weeks we have also highlighted the collective litigation and advocacy work that has been carried out by more than 40 organizations concerned with the freedom and health of migrants in the framework of the pandemic: These actions are reflected in various webinars, communications to federal and state authorities, law suits, a complaint to the National Human Rights Commission (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos), reports and calls to action.

Advocates are perhaps most hopeful of the unprecedented success seen recently in the courts. Some of these organizations filed a constitutional legal action and the court issued a favorable historic resolution, an injunction ordering immigration authorities in Mexico to immediately release migrants belonging to vulnerable groups that are currently detained and to ensure that no child is detained in a detention center. These are two of 11 measures ordered to safeguard the life and health of the more than 2,000 migrants and asylum seekers that immigration authorities have reported in detention. Legal actions continue in various states in the country, in order to keep up the legal pressure for immigration authorities to comply with the order, of which to date there has been no notification.

At the time of writing, it appears that this collective advocacy is having some impact and IDC Americas has received reports that apprehensions have slowed down and many detained migrants have been released in Mexico in recent weeks, albeit without a formal procedure. It is unclear what actions immigration authorities will take in the coming weeks. The advocacy challenge remains to establish release procedures with screening and safeguards, as well as referral to post-release support structures. IDC Americas joins our Mexican partners in working on a range of proposals to develop and implement alternatives to detention for those released or at risk of further detention. Of additional concern is that deportations continue, as Mexican immigration authorities have been concentrating detained migrants in the three largest detention centers of Mexico City, Acayucan and Tapachula, deporting some through negotiated agreements with Central American governments.

Furthermore, Amnesty International Mexico has called on the country's highest Covid-19 authority, the Undersecretary of Health Prevention and Promotion, to back these calls for release of detained migrants and asylum seekers to protect their health and to make a public plea to immigration authorities in this regard, as well as providing access to housing and health services to the migrant and refugee population in Mexico.

The next few days will be crucial for Mexican migration and health authorities whose duty is to put migrant's right to health above immigration control in order to reduce the risks of Covid-19 infection among this population.

Further north in the region, advocates in the United States have been amongst the most active, progressive and vocal on calling for release of the tens of thousands currently held in immigration detention centers and jails around the country. Two new reports, the first from the Detention Watch Network and the second from Amnesty International, clearly demonstrate the high risk to the lives of migrants in detention and the collective public health threat posed by unnecessary immigration detention.

Advocacy strategies range from litigation for release of immigrants from detention to important community organizing through broad national campaigns that also amplify state and local actions, such as Detention Watch Network's call to #FreeThemAll. Further, nearly 200 state, local and national organizations worked with Congress to support the Federal Immigrant Release for Safety and Security Together Act (First Act) to work toward the release of people from detention. The Act provides urgent and critical restrictions on immigration detention and enforcement during this unprecedented national public health emergency to protect immigrant communities and collective health. You can read their letter of support.

Several of IDC's member and partner organizations have shared a range of useful collective research and advocacy tools and resources in response to Covid-19.

Detention Watch Network developed and shared on its website key messaging guidance on Covid-19 and immigration detention and a useful toolkit to support local demands for mass release from ICE custody.

The Vera Institute of Justice has shared Guidance for preventative and responsive measures to coronavirus in immigration detention

Freedom for Immigrants launched a section of their National Immigration Detention Hotline specifically to respond to Covid-19. With social visitation indefinitely suspended, this court-protected hotline is one of the few free and confidential resources available to maintain communication with people in detention. They are also providing people across the United States with housing post release through a network of volunteers and a house they operate in Louisiana.

Freedom for Immigrants also released an interactive real-time map that tracks the number of cases in U.S. immigration detention and the government's failure to adequately respond to this pandemic. They have so far documented over 100 confirmed Covid-19 cases since the first person was diagnosed in late March. This tool tracks reports of isolation and quarantine measures in responses to Covid-19, noting their implementation in an ad hoc and dangerous way. Detention staff failure to observe proper health protocols and extreme inadequate medical responses during lockdown, resulting in substantial risk to both detained and non-detained populations, are also documented.

One initiative to watch in the coming weeks is Justice in Motion´s recently launched Child Detention Crisis Initiative, which will work through their Defender Network to bring together advocates from the United States, Central America and Mexico to free migrant children from U.S. immigration detention and reunite them with their families.

Finally, on April 26, the immigration authorities reported through a bulletin that they had emptied almost its entire population from detention centers. There are many criticisms of the lack of a program of alternatives that would have allowed the channeling of migrants to hostels or hotels, instead there were massive deportations, even of childhood and adolescence, to places that could be a risk for them, not only of getting Covid-19. There is still a need for coordination between actors to guarantee the right to health of people who are still in Mexico through a program of alternatives managed by authorities and civil society.

Mexican Advocates Defend Rights of Detained Migrants

IDC stood together with over 200 organizations calling for a reversal of the Mexican government's decision to deny civil society organizations access to immigration detention centers across the country. The new policy decision, shared in a government public notification in late January, came on the heels of publicized reports by migrant advocates of repeated difficulties in entering the most populated detention centers on the country's southern border and in Mexico City, and an open letter from Amnesty International urging that the National Migration Institute (INM) guarantee access of civil society organizations to detained migrants and refugees.

This issue has become more pressing in recent weeks within the context of militarized use of force by the Mexican National Guard at entry points on the southern border and rising concern about the expansion in the use of immigration detention in Mexico's strengthened containment and migration control policy towards Central Americans hoping to enter and transit Mexican territory in mass caravans. For the people moving in the caravan this January, all roads led to being deprived of their liberty – whether they expressed their intention to apply for asylum or a humanitarian visa, or whether they took up the government's offer to stay and work in Mexico's southern states, they were taken into detention.

Release from detention amidst fast-track deportation policies and procedures, depends almost always and primarily on access to legal advice, knowing your rights and having someone on the outside advocating for you. There is currently no information publicly available as to how many of those detained have been released or able to continue their immigration procedures for asylum, or humanitarian or visitors´ visas in freedom.

On January 30th, advocates held a press conference urging the Mexican government to restart programmed visits and eliminate the new obstacles facing NGOs who have requested permission to enter the detention centers. The message they sent is that it is not acceptable to violate the rights to access of information, access to justice and due process of migrants and refugees subject to international protection for even one day. They also urged the government to accept the request made by the Inter American Commission on Human Rights to visit the immigration detention centers currently holding thousands of people on Mexico's southern border.

CIvil society organizations held a press conference urging the Mexican government to restart programmed visits and eliminate the new obstacles facing NGOs who have requested permission to enter the detention centers.

Media statements made by IDC members Alejandra Macías Delgadillo, director of Asylum Access Mexico and Elba Coria Márquez, director of the Ibero University´s Refugee Law Clinic, highlight the risks associated with prohibiting detained persons from accessing legal defense, whether in asylum claims or to monitor due process in detention and deportation procedures. These risks are even greater in the absence of adequate registration, screening and individualized interviews, and effective procedures to identify protection needs in today´s detain and deport mechanisms.

Interview to Elba Coria Márquez, Director of the Ibero University's Refugee Law Clinic, about the situation (Spanish).

Finally, several agreements were reached in an unprecedented meeting held with INM commissioner and the National Discrimination Commission (CONAPRED), including revocation of the policy made only days earlier to suspend civil society monitoring of immigration detention.

Immigration detention in Mexico in many ways is similar to the penitentiary model and represents significant expenditure of public funds, as outlined in a 2019 analysis of the immigration detention system carried out by AsiLegal, Fundar and Sin Fronteras. The systematic violation of rights of detained persons has been documented in over 15 years of immigration detention center monitoring reporting by Mexican civil society. In this light, IDC supports efforts to guarantee systematic civil society monitoring of conditions of detention and the exercise of right to information and legal defense of detained migrants and refugees.

In this respect, IDC has made available a Monitoring Manual, produced jointly with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Association for the Prevention of Torture (APT). It is a step-by-step guide for anyone or any institution carrying out immigration detention visits. It can also be used as a checklist for authorities, detention center staff and journalists on the standards that need to be applied when asylum-seekers and migrants are detained.

Alternative Care Models for Migrant Children Protection Protocol

On Mexico's southern border, IDC supports alternative care models and strategies for strengthening local implementation of Mexico's Migrant Children Protection Protocol

IDC Americas brought 2019 to a close with the third regional Forum for exchange and strengthening among local and federal authorities, as well as civil society organizations and international organisms working in support of migrant children. On this occasion the Forum was hosted in Chiapas, a state on Mexico’s southern border. The objective was to identify the obstacles and opportunities presented by the implementation of Mexico's Migrant Children Protection Protocol, at all times preventing migrant detention in this population.

A video was screened at the beginning of the event, featuring the opinions and reflections of various young migrants currently living at a secondary reception facility. In this video, they talked about their experiences, for the most part traumatic, of having been locked up inside a detention centre for various lengths of time. This exercise served as a guide for the sessions and so that participants bore in mind the reasons why being deprived of liberty on migration grounds is incompatible with a child’s best interests.

In the first panel on best practices, Mexico’s Child Protection Authority [Procuraduría Federal de Protección] shared the work carried out in Tapachula, a city on the border with Guatemala, as a result of the mass movements of people entering through this city last year, featuring significant numbers of child migrants. For its part, the Comitán regional protection authority highlighted a success story in which a group of children were taken out of a migrant holding centre and placed in a secondary reception center. Finally, SOS Children’s Villages [Aldeas Infantiles] spoke about how the organization had to adapt their care model to new necessities, which in this case include operating as a support centre for migrant children in primary and secondary reception facilities.

The Executive Secretary for Mexicos’ National Child Protection System [Sistema Nacional de Protección Integral de Niñas, Niños y Adolesentes, or SIPINNA] went over the process for creating the System’s Commission for Child Protection [Comisión de Protección de niñas, niños y adolescentes] and the adoption within the aforementioned Commission of the Migrant Children Protection Protocol as part of efforts to prevent children from remaining in detention.

Finally, the American organization KIND presented a system for the protection of children in the United States such that the authorities and civil society are aware of the options available to those children with family in the country.

The second working day was dedicated to discussions in working sessions which dealt with the various phases of the protection protocol, such as identification and evaluation, determination of best interests, restoration of rights, implementation of initiatives and the monitoring of “plans for life”. The working sessions showed consensus on topics such as a lack of both resources for protection authorities and available space for receiving migrant children. Specialized attention for different types of migrants was posed as a challenge, as well as the need to generate synergies with those individuals or entities that give support in each phase of the protocol.

Noteworthy among best practices are the efforts made by the protection authorities to work jointly with civil society in legal representation and in implementing plans for the restoration of rights, as well as in coordinating among authorities. This area highlighted the efforts made to obtain statistics for child migrant protection and to place them in primary and secondary reception centres.

Without doubt, these spaces serve to create support networks among those responsible for protection, in order to understand the processes and opportunities for advocacy, as well as to adopt certain commitments resulting in the local-level implementation of the protection protocol in support of liberating children from migrant holding centres within the framework of an alternative care strategy.

Interview With the IDC Americas Team

Interview with Diana Martínez, IDC Americas Program Officer on the current conditions of migration in the region

How are you, through IDC, confronting the increased security on the borders and the rise in immigration detention in the region, and what elements most concern you?

Governments in the region have a series of international human rights commitments that they have acquired through the years. We try to push them to fulfill these commitments, particularly the right to freedom, in accordance with the international standards that the authorities themselves have imposed, Governments should not forget the protection they should guarantee to vulnerable groups by not placing them in detention, both children and adolescents as well as refugees and other vulnerable groups.

How has the perception of the region changed in the light of the new situation?

Without a doubt there has been an important shift in the situation over the past months. Countries like Mexico had been making progress in issues around protection and alternatives to detention after years of not knowing what alternatives to detention meant. The Mexican government had been gradually including this within its agenda and discourse, and even began some pilot projects of alternatives for children, adolescents and refugees. For months, Mexico was considered a reference for good practice on an international level.

As IDC, we saw this as a step towards what we envisage, that all detention for migrants will be done in accordance with the principles of exceptionality, proportionality and necessity. In other words, that immigration detention will be used only in exceptional circumstances and never for vulnerable groups.

Unfortunately, following the agreements with the United States, this progress has reached an impasse, and we are seeing that immigration detention has once again become one of the main tools of migration control, and that much more control is being exerted on the border and along the migration route. This is not only in Mexico, the Central American countries are doing something similar, trying to close the borders to prevent people from leaving. With this, governments are forgetting that people have the right to seek a better life and request asylum if they are being persecuted or if their lives are in danger.

Governments are forgetting that people have the right to seek a better life and request asylum if they are being persecuted or if their lives are in danger

How many detention centers are there currently in Mexico and what kind of centers are they?

There are currently approximately 60 formal detention centers spread throughout Mexico. There are various categories of detention, the most well-known is the migrant detention center (estación migratoria), but there are also temporary holding centers (estancias provisionales), type A and B*, that are different to the previous ones in that they receive people for short periods of time. On the other hand, we have centers that have been set up in the wake of the agreements with the United States in June of this year. These are 8 temporary (or informal) shelters (albergues temporales) that have greater capacity than the detention centers and are strategically located in some states along the migration route. These centers have increased the capacity of the Mexican government to detain people.

This concerns us because firstly, evidently, the detention conditions are not optimal and second, it is not clear whether international organizations and civil society are able to enter these centers nor whether the detained people are receiving information about their migration procedures, or about the possibilities for legalization and of the importance of having access to asylum procedures. On the other hand, not knowing when these temporary shelters will be closed is also a worry.

What are the latest figures for immigration detention?

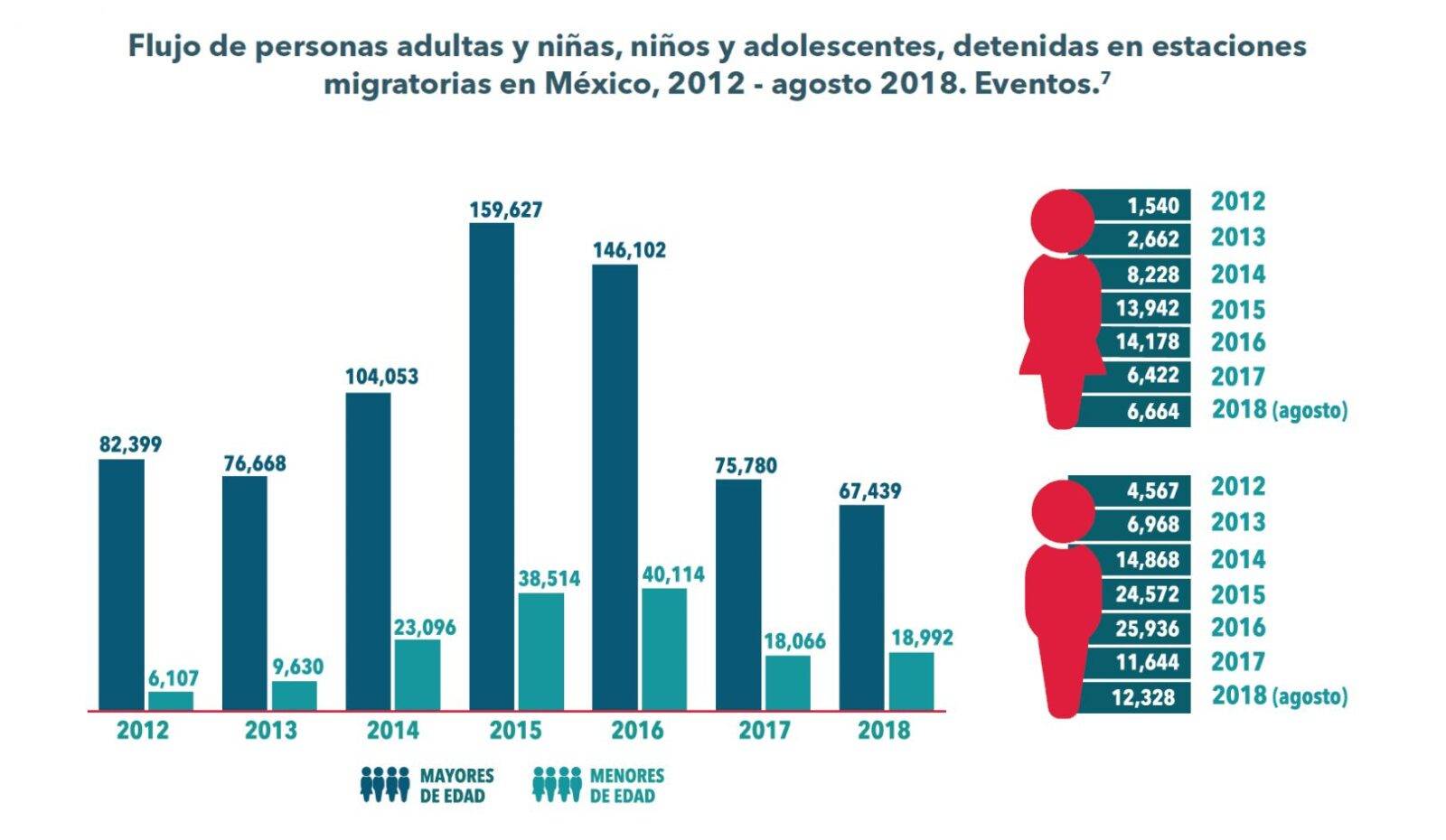

In statistics provided by the government’s Migration Policy Unit, between January and August of this year, 144,591 immigration detentions have been carried out in Mexico, with 43,027 of those being children.

What is IDC actively working on in the face of the increase in migrant detentions in the region?

IDC is betting on local efforts, especially in Mexico and the United States. We argue that local responses can bring about global change. We are driving the coordination between diverse stakeholders, and supporting the strengthening of protection and migration authorities as well as civil society organizations, in order to move forward in the implementation of alternatives to detention, mainly that of children and adolescents, but also that of their families.

The issue of accompanied children and adolescents has us particularly concerned and we worry that they are overlooked because they are with a family member. The government is making some effort to relatively quickly free children and adolescents who travel unaccompanied (although the ideal would be that they do not spend even a day in detention), while accompanied children are left in detention centers for indefinite periods with the excuse that they are with family. Detention continues to be detrimental to these children and adolescents. We are collaborating with our members and allies, as well as with authorities (through alliances, events and trainings) to ensure that alternatives are implemented as part of a protection protocol for migrant children and that the existing provisions in Mexican law - that no child under the age of 18 should be detained for migration reasons - becomes a reality.

IDC is betting on local efforts, especially in Mexico and the United States. We argue that local responses can bring about global change.

What opportunities do governments in the region have?

They have a great opportunity to fulfill the commitments they have undertaken; to respect the human rights of the population that inhabits their territory, to monitor international standards, and above all, to enable the protection of children in situations of human mobility. They could even elevate standards and reverse the securitization that is occurring again in the region and that is affecting the most vulnerable who do not have access to travel documents to reach Mexico or the United States.

It is in governments’ hands to change the situation of the most unprotected of these vulnerable groups who leave their countries in order to safeguard their lives and their freedom and who are experiencing the impossibility of accessing migration procedures, international protection or who are being detained for long periods in detention centers both in Mexico and the United States.

________________

*In accordance with the National Migration Institute´s Detention Center Regulations (Normas para el funcionamiento de las estaciones migratorias y estancias provisionales), temporary holding center “A” allows a maximum stay of 48 hours and “B” allows a maximum stay of 7 days.

Solidarity Calls for Ending Immigration Detention

United in the belief that immigration detention is not a solution and that we need to create new perspectives, IDC and the Campaign to End the Immigration Detention of Children joined forces this month with the translocal migrant movement Flourish Here and There. On July 6th, Mexico City's historic grand square, the Zócalo, filled with art, music and the voices of those who for some reason had to leave their countries, in an act of solidarity in favor of local well-being across borders: migrant, refugee, deported, returned, detained and undocumented persons, citizens, families, neighbors and communities.

The importance of hearing migrant voices, many of them having lived through the experiences of detention and deportation, cannot be overestated at this critical time of acute criminalization of human mobility. The so-called “crisis” we face as a society is that of normalizing discrimination and making xenophobia acceptable. Celebrating the realities of migration and the hope that characterizes it, through music, dance, art, children's books and activities, is undoubtedly part of the solution.

The spirit of inclusion and solidarity brought together artists in pro bono collaboration, including three cumbia djs, the rapper Dayra Fyah, the migrant ensamble “Latido Nómada”, the band the Mexican Standoff from Los Angeles and the Singing City Choir from Philadelphia, the publisher ateconqueso, the social innovation group Activate Labs, many many volunteers, with migrant groups and partner organizations in Mexico, Central America and the United States.

Invited by the organization Otros Dreams en Accion (ODA), they presented 6 joint proposals, symbolically represented (by binational artist Emily C-D) by a carpet in the shape of a mandala made of seeds, grains and flowers that remind us of human mobility, freedom of movement, nourishment, the ability to grow and flourish in different places, and painted posters in the hands of a compass that guides us.

- Abolish Migrant Detention: Detention and deportation are not part of the solution.

- Families belong together: Separating migrant families is a crime against humanity.

- Diverse communities: Natural ecosystems thrive with diversity, and human culture is no exception. Discrimination is dehumanization, lives are on the line.

- Safety and inclusion: Safety and inclusion for all migrants creates safer communities for all of us.

- Education and jobs: This is the key for strong (trans) local economies.

- People before papers: Documents should create access instead of inequality.

Solidarity spreads and parallel events were held in other cities: in San Pedro Sula, San Salvador, Guatemala City, Tapachula, Ixtepec, Queretaro, Tijuana, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Seattle, Chicago, Atlanta, Staten Island, and Brooklyn.

For more information, to join the campaign or make a donation visit Florecer aquí y allá.

To learn more about alternatives to detention visit How IDC Defines ‘Alternatives to Detention’

How IDC Defines ‘Alternatives to Detention’

Even though the phrase ‘alternatives to detention’ is present in numerous international human rights instruments, it is not an established legal term or a prescriptive concept. In fact, different stakeholders often use varying definitions of the term. As a working definition, the IDC understands alternatives to detention to mean: “any law, policy or practice by which persons are not detained for reasons related to their migration status.”

For IDC, alternatives to detention (or ‘ATD’) are a key element of the strategy to limit and end the use of immigration detention; and for this reason, we choose to use a broad definition. This expansive definition incorporates a range of options available to governments to manage migration without resorting to detention. By compiling different ATD examples found in law, policy and practice, we’re able to offer ideas and starting points for each country to continue to limit use of immigration detention and ensure detention is not being implemented illegally or unnecessarily.

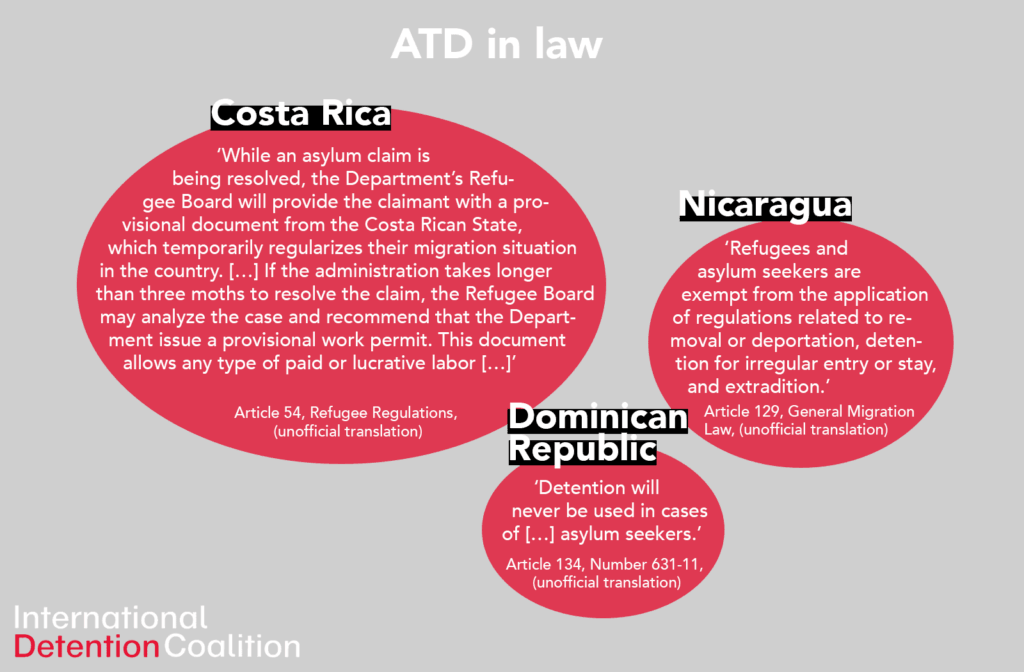

ATD in law

For example, when we discuss ATD in law, we are able to point to examples in Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, among others.

Often, ATD in law limits the use of detention by prohibiting it for certain groups of people, especially those in vulnerable situations. IDC

recommends that laws include a mandate to explore ATD implementation before resorting to detention, as well as judicial review of all decisions to deprive someone of their liberty.

ATD Policy

An important distinction between implementing ATD in law and implementing ATD policy, is that sometimes the latter is more accessible to governments given it is not required to pass through a legislative process. For example, in Mexico, immigration and refugee authorities coordinate with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and civil society organizations to implement a release program from asylum seekers. People seeking asylum in Mexico can be released from immigration detention to live in the community in their own home or in a shelter. They are obligated to periodically report to authorities during their asylum process, while UNHCR and civil society organizations provide support to help them satisfy their basic needs.

ATD in practice

ATD in practice often depend on participation by civil society organizations for their operation, and in some circumstances, without any government support. For example, in the US, the Interfaith Committee for Detained Immigrants operates a group home for men where they can live and continue to participate in their migration or asylum process. The home functions as an ATD in practice for people who have been released from detention, although the program does not receive support from the US government.

In countries where immigration detention is the exception rather than the rule, ATD in practice are highly diverse and are often integrated into social services and national protection or public support systems that are available to all people living in the community, both immigrants and nationals.

ATD exist and are effective

IDC’s body of research shows that the most effective ATD in terms of reaching legitimate government aims and guaranteeing human rights are those that involve both government and civil society in their development, implementation and evaluation.

While none of these ATD examples are perfect, they demonstrate the variety of options available to governments to carry-out migration management without the use of detention.

Unfortunately, we continue to observe that the primary focus of ATD implementation is still enforcement and control mechanisms, such as restrictions on freedom of movement, bail or bond, and reporting requirements. These mechanisms seek to promote compliance with immigration procedures but have generated little evidence of effectiveness.

Instead, a growing body of research and evidence shows that the most effective ATD are those that engage migrants in immigration and asylum procedures, in particular through tailored case management. This involves a social work approach, and is a comprehensive strategy to provide specialized support with migrants, empowering them to participate in decision-making as they navigate complex legal and administrative migration processes.

Learn more:

Frequently Asked Questions about ATD

More ATD examples from the Americas and around the world

Elements of the most effective ATD and the Community Assessment and Placement Model: There Are Alternatives

Latest Evidence for Ending Family Detention

Written by Dr. Robyn Sampson

Senior Advisor, International Detention Coalition

The program demonstrates that case management works in achieving immigration compliance at a tiny fraction of the fiscal cost of detention and without the human cost and cruelty of separating families or detention.

The Women’s Refugee Commission in the US has released a new evaluation of the Family Case Management Program, which operated in the United States between January 2016 and June 2017. This government-funded program was designed to test the effectiveness of tailored supervision with vulnerable families - such as pregnant women, nursing mothers, and families with special needs children - who were waiting for their immigration court hearings.

Holistic Case Management Approach

The program was designed on the basis that meeting basic needs, exploring all options in the individual case, and building trust would result in participants who were more ready, willing and able to comply with all aspects of the immigration process. The FCMP service framework involved three main components:

- Monitoring Individualised and interactive compliance monitoring with dedicated ICE Officers

- Low caseload ensures on-going supervision of cases and rapport with participants

- Access Access to community based services

- Facilitates community services individualised to participant needs through a professional trusting relationship

- Orientation Mandated orientation programming for participants

- FCMP staff and officers act as “system navigators”

Together, the three components served as a method to promote compliance while allowing participants to remain in their community as they moved through the immigration process.

The program was contracted by the government to GEO Care to provide holistic case-management services on an estimated 20:1 family unit to case manager ratio. This company then partnered with community-based social service and faith-based organizations to provide additional support services. In addition, GEO Care partnered with legal assistance programs to ensure clients access Know Your Rights presentations and other forms of basic legal information exchange. The head of household for each family was required to attend a legal orientation program providing information on their legal obligations, immigration proceedings and basic US laws.

Case managers worked with each family to develop a family service plan and to facilitate access to community services. This included support for participation in immigration processes, such as departure planning and preparation support, as well as referrals for legal, medical, food, education and other basic needs.

The program was offered in Baltimore/Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles; New York City/Newark; Miami; and Chicago. Each of the five locations was able to manage up to 160 family units, making for a total capacity of 800 family units across the program.

Outcomes

A total of 2,163 people - made up of 952 heads of household and 1,211 dependents - participated in the program. An internal evaluation by the main provider found the holistic case management approach produced strong results. The program recorded 93% attendance at legal orientation, 99% attendance at court proceedings, 97% program check-in compliance, and an 87% favourable rate when a participant was terminated from the program. The program also produced independent departures, and better coping and wellbeing outcomes for children and families. The program cost US$36 per day per family, compared with US$140 per person per day in adult immigration detention, and $798 per family in family detention. Further improvements identified during the WRC evaluation, as well as a longer program operation period, would have likely created even better outcomes.

Conclusion

The IDC’s body of research shows that There Are Alternatives that are effective, affordable, and humane. The US Family Case Management Program provides even further evidence that case management focused on meeting basic needs and providing trustworthy advice will result in high compliance rates, low costs, and less harmful alternatives to detention.

Further Reading

- Women’s Refugee Commission. 2019. The Family Case Management Program: Why Case Management Can and Must Be Part of the US Approach to Immigration. New York: WRC.

- GEO Care. 2017. Family Case Management Program: Summary report. GEO Care (on file with IDC)

- Loiselle, Mary F. 2016. "Geo Care's new family case management program." GEO World, 2-3. Accessed 23.03.2017 at http://www.geogroup.com/userfiles/1de79aa6-2ff2-4615-a997-7869142237bd.pdf

- Sampson, R., Chew, V., Mitchell, G., & Bowring, L. (2015). There are alternatives: A handbook for preventing unnecessary immigration detention (Revised). Melbourne: IDC.

IMPORTANT: Call for Inputs on Immigration Detention

WHAT: The Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families has decided to elaborate General Comment No. 5 on Migrants’ Rights to Liberty and Freedom from Arbitrary Detention. This is a critical opportunity to provide input and feedback on fundamental human rights issues. The Committee invites all stakeholders to provide inputs to this initiative through a questionnaire by 1 April 2019. The concept note and questionnaire are available in English and Spanish HERE.

HOW: Please send responses electronically in Word format to [email protected] with subject line “Submission for General Comment on Migrants’ Right to Liberty.” Submissions should not exceed 10 pages. Written submissions will not be translated and should preferably be submitted in English, however submissions in French and Spanish will also be accepted. All submissions will be posted on the webpage of the Committee unless explicitly indicated to the contrary.

Any questions should be addressed to the Secretary of the Committee, Mr. Luc Mubiala, at [email protected].

If you would like to inquire about being connected to other organisations in your region also working on responses, please contact the following IDC regional offices:

Americas [email protected]

Europe [email protected]

Africa [email protected]

Middle East & North Africa [email protected]

Asia Pacific [email protected]

An Opportunity for the New Administration in Mexico

More than 90,000 people were held in immigration detention in Mexico in 2017, a policy that has been shown to be expensive and harmful. Of these 90,000, more than 18,000 children and adolescents were detained because of their migration status, despite the fact that current legal framework prohibits it.

Image: Numbers of adults (dark blue), children and adolescents (teal) held in immigration detention in Mexico, by year, January 2012 – August 2018 (Source: Official government statistics)

Mexico has a new administration, and the IDC has outlined how alternatives to immigration detention present an opportunity for reform that respects the right to liberty.

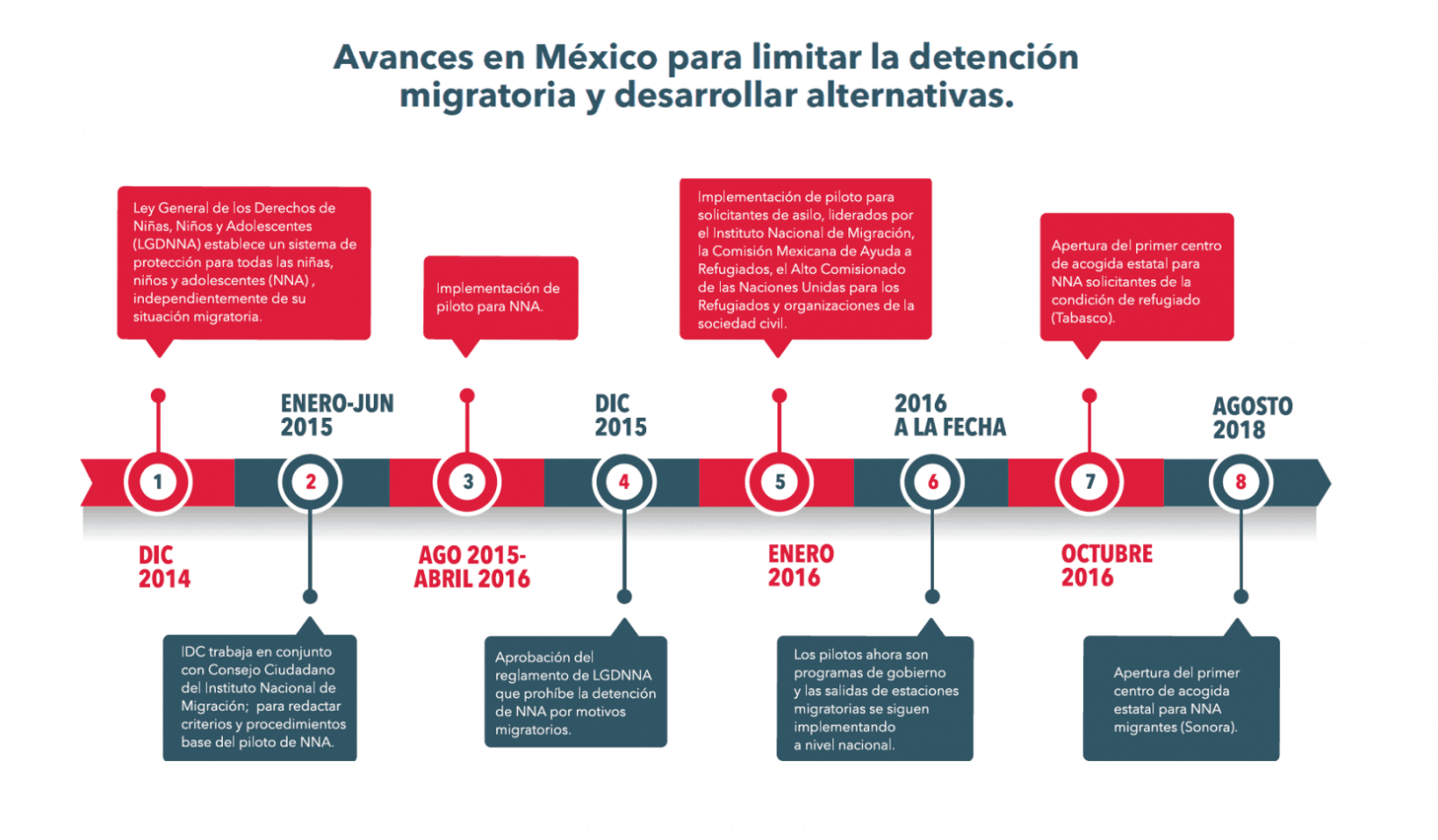

Mexico has already made significant progress to develop alternatives to immigration detention for those who are in vulnerable situations, such as children and asylum seekers. In 2014, new legislation established a national protection system for all children, regardless of their immigration situation; and since then, successful pilot projects have demonstrated how children and families can be supported to live in the community as they participate in their ongoing migration or asylum process.

Image: Progress made in Mexico to limit immigration detention and develop alternatives

The IDC has identified current opportunities available to the Mexican government to limit the use of immigration detention and strengthen the use of alternatives. It urges the State to develop, promote and invest in joint programs, between authorities and civil society, which uphold migrants’ rights and meet the requirements of the State.

Concerns Immigration Detention Could Increase in US / Mexico Funding Agreement

The US Government announced it will provide $20 million in foreign assistance funds to the Mexican government to pay plane and bus fares to deport as many as 17,000 people, preventing them from moving onwards to countries where they may be able to seek asylum. The decision was made despite strong opposition from members of Congress and civil society.

The US Government announced it will provide $20 million in foreign assistance funds to the Mexican government to pay plane and bus fares to deport as many as 17,000 people, preventing them from moving onwards to countries where they may be able to seek asylum. The decision was made despite strong opposition from members of Congress and civil society.

The Mexican government released this statement saying that the proposal is still under evaluation, and reiterating Mexico's commitment to promote orderly, legal, and secure migration with full respect for human rights and the international legal framework. Mexico is currently one of the Co-chairs of the UN Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

If the assistance funds were to be provided by the US Government, they would compromise an individual’s right to seek asylum in the country they deem safe and prevent governments from achieving their international obligations to offer an individual access to protection.

The IDC joined over 25 organizations expressing concerns over this development, and making practical suggestions for how these funds could be used to provide efficient and affordable solutions, rather than increasing the use of immigration detention.

This funding has been linked to conversations about an agreement to make Mexico a "Safe Third Country" for asylum seekers, which IDC and our Members have strongly opposed since last May.

The IDC position remains the same - emphasizing that cooperation between the United States and Mexico on migration management should prioritize respecting the rights of asylum seekers in both countries. Both States stand to benefit if they prioritize regional cooperation that focuses on upholding human rights and promoting durable solutions.

The letter states, "U.S. assistance to Mexico should not be directed towards increased detention and deportation and should not support migration and security agencies that have few mechanisms to hold their agents accountable for the abuses they commit against migrants. Moreover, the United States should not be outsourcing its immigration enforcement to Mexico. Instead the United States should support the efforts of the UNHCR and civil society organizations in strengthening regional protection mechanisms..."