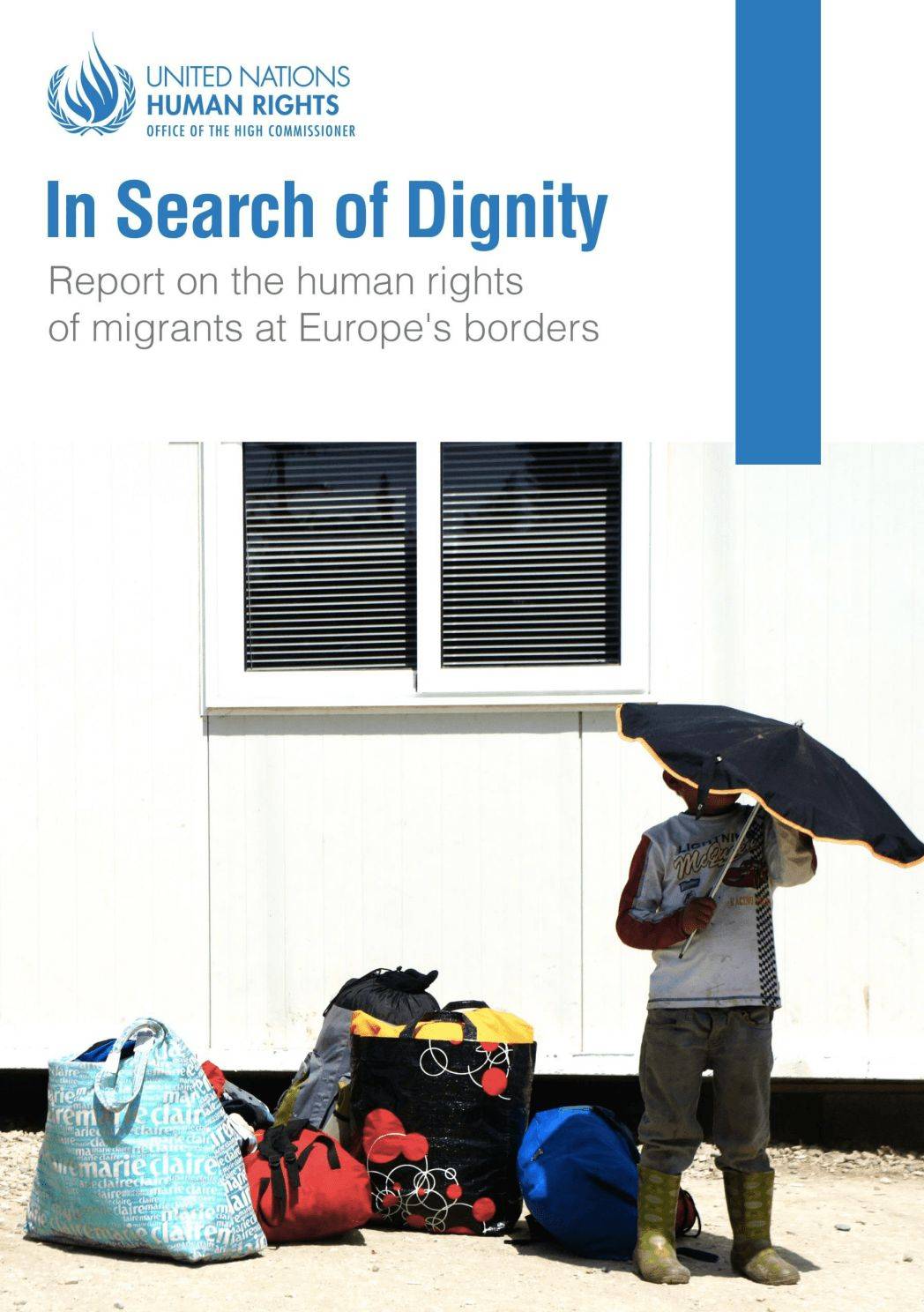

OHCHR Report: “In Search of Dignity: report on the human rights of migrants at Europe's borders”

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has published a new report: In Search of Dignity: Report on the human rights of migrants at Europe’s borders. The report documents the findings of the human rights monitoring missions to transit and border locations in Bulgaria, France, Greece, Italy and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia held during 2016.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has published a new report: In Search of Dignity: Report on the human rights of migrants at Europe’s borders. The report documents the findings of the human rights monitoring missions to transit and border locations in Bulgaria, France, Greece, Italy and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia held during 2016.

Several sections are relevant to immigration detention and alternatives to detention, providing practical guidance to the States visted and European Union insitiutions as applicable.

“The teams encountered poor conditions in detention, some of which could amount to inhuman and degrading treatment. The poor conditions included overcrowding; children being held alongside unrelated adults; frequently dysfunctional toilets or other sanitary facilities; showers in spaces which posed a risk for the safety of women and girls; structures that are unfit for children; lack of adequate and sufficient water and food of nutritional value; and lack of access to quality physical and mental health care and services.” OHCHR report

Report findings include:

- In many countries visited migrants, including children, are subjected to detention practices, including mandatory detention in some jurisdictions. Individual assessments to determine the necessity and proportionality of detention or to identify less restrictive alternative measures were not conducted according to the report.

- the deprivation of liberty contravened national constitutions and international human rights law as there was no legal basis for the detention of migrants beyond an initial 48 or 72-hour time limit.

- Most migrants were held for multiple days, and sometimes weeks or months, in immigration detention facilities and were unaware the reasons for their detention or the possibility of challenging their detention.

- Some previously open reception centres or other facilities had been converted into highly securitized detention centres, where often both adults and children were held.

- The teams raised the need to work with the authorities to develop alternatives to detention.

- Facilities visited did not provide a reception environment or reflect appropriately the administrative nature of immigration detention. The centres were generally heavily securitized; surrounded by razor and barbed wire fences; kept under surveillance by armed police, military or other security guards; and sometimes contained enclosures where, based on age or nationality, migrants were detained separately and unable to move within the detention facility as other migrants.

- Children were subjected to arbitrary and prolonged immigration detention and to abusive treatment and inhuman conditions in detention, without access to education, health services or meaningful recreational activities.

- Attempts to protect the rights of the migrant children encountered during the missions were manifestly inadequate and often detrimental to the effective protection of migrant children’s rights, regardless of whether children were staying in informal, formal, open or closed facilities.

Image: OHCHR

OHCHR made several recommendations for States, including:

- Prevent indefinite or protracted detention of any migrants who cannot be returned and protect them against redetention.

- Make available sufficient and appropriate shelter spaces for migrants in vulnerable situations and not place them in detention facilities.

- End all mandatory detention policies and practices immediately.

- Establish a presumption against immigration detention in law, restating the right to liberty for all persons, regardless of migration status. States should immediately and expeditiously cease the detention of children on the basis of their migration status or that of their parents.

- Ensure that any deprivation of liberty has a legal basis in national law, which defines clearly the legitimate purposes for any detention, its limited scope and duration, and is sufficiently narrow to avoid mandatory detention of a broad category of person.

- Implement robust due process and fair trial guarantees, ensuring that immigration detention is only ordered by a court of law on a case-by-case basis, as an exceptional and last resort measure and for the shortest period of time, after it has been deemed necessary and proportionate, and no suitable non-custodial alternative has been identified. Ensure migrants have access to information, translation, legal aid and assistance, and the possibility to challenge the lawfulness of any deprivation of liberty.

- Ensure and facilitate access and communication for civil society organizations providing legal assistance to migrants held in immigration facilities.

- Develop national action plans to implement human rights-compliant, non- custodial, community-based alternatives to detention based on an ethic of care, inot enforcement.

- End any form of detention of children on the basis of their or their parents’ migration status, including in prisons or police stations.

- Ensure that in all facilities where migrants are held the conditions reflect the administrative purpose for which migrants are being detained. Specifically, States should take measures to ensure that facilities do not resemble prisons and that there is a reasonable balance between the numbers of security staff and those providing services for migrants.

- Ensure sufficient numbers of trained and specialized staff are hired in order to respond to the protection needs of migrants in detention.

- Establish standardized systems for the determination of the best interests of the child, carried out by trained child protection staff, in a child-friendly manner, and guaranteeing children’s rights to express their views freely in all matters affecting them and have their views taken into account in accordance with their age and maturity.

The report also provided a number of concluding recommendations that enable advocacy for alternatives to detention to strengthened. These included:

- Ensure and facilitate unrestricted access of independent monitoring bodies, including national human rights institutions, ombudspersons, national preventive mechanisms and other relevant bodies to all locations under the jurisdiction or effective control of the State and to all information that is required to effectively monitor the human rights of migrants. Monitoring should extend, as applicable, to arrival, shelter and reception of migrants, border processing and interviewing, transfers, detention situations, pre-removal processes, and return processes.

- Enable civil society actors to participate in monitoring and evaluating the human rights impact of governance measures.

- Establish mechanisms by which the implementation of the recommendations from the independent monitoring bodies can be facilitated and ensured.

- Establish accessible complaints mechanisms for migrants to report to without fear of retribution.

- Ensure effective accountability of private actors carrying out migration governance functions, including by adopting or amending legislation to ensure that the actions of private actors do not undermine human rights and that any wrongdoing is sanctioned.

Read the full report here

More Information

OHCHR - Full press release

A unique alternative to detention model in Barcelona

The city of Barcelona has created a local resident status to provide rights and reduce the risk of detention for undocumented migrants.

While the city of Barcelona faces independence protests, an innovative model has developed to protect vulnerable undocumented migrants at risk of detention and destitution.

Calling itself the ‘City of Rights’, the local municipal government under the leadership of Deputy Mayor Gerardo Pisarello has undertaken strategic litigation against the federal government’s use of immigration detention in the city on the basis that there was no permit for it to operate.

With more than 50% of all migrants in Spain at some point being in an irregular status, undocumented migrants are at particular risk of detention under federal law, including in the federal immigration detention facility in Barcelona

In response, the municipality responsible for migrants , Migrant Care and Hosting Department for the City of Barcelona, ‘Ajuntament de Barcelona’ – Acolida a immigrants’ has also developed a unique and integrated alternatives to detention model for undocumented migrants.

The model includes:

- Active local registration (padrón) - Registering undocumented migrants in the city- which automatically allows them access to mainstream services and triggers the period from which they can seek regularisation.

- Providing a status to reside in the city- Developing a unique document ‘Document de banaca’-neighbourhood document- to give local level status for undocumented migrants. It is now also being regionally acknowledged by the Catalan state authorities, who issues health care card for residents.

- Access to essential services, including education, health, housing support and welfare for at risk cases

- Encouraging regularisation- 14,000 undocumented migrants have been assisted from the legal advice provided by more than 60 lawyers. The municipality has funded EU200,000 towards this work.

- Promoting amendments to legislation to ensure more inclusive policies and reducing the use of detention and allowing greater regularisation of undocumented migrants. This work has included advocacy work at the EU level with PICUM.

Ramon Sanahuja Velez, the program director, argues that this program provides a range of benefits to the city and the migrants. This includes practically ensuring a vulnerable hidden population at risk are included in society, benefiting the economy and enhancing human rights.

More information on the program can be found here.

Plans for alternatives to detention in Madrid

Meanwhile, the City Council of Madrid is also planning to offer alternative to the deprivation of liberty and safeguards the human rights of migrants in detention. The local government aims to provide placement options for those in need as an alternative to detention and to hire social workers who could provide support for and monitor the situation of the detainees in the city’s detention centre.

Building evidence for alternatives to detention in Poland

Katarzyna Słubik works for IDC Member Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej ( SIP - the Association for Legal Intervention) based in Warsaw, Poland. Here she reflects on her recent attendance that a workshop coordinated by IDC and it's application in her national context.

Katarzyna Słubik works for IDC Member Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej ( SIP - the Association for Legal Intervention) based in Warsaw, Poland. Here she reflects on her recent attendance that a workshop coordinated by IDC and it's application in her national context.

--

Last August, I travelled to Mexico for a first ever Global Meeting of Alternative to Detention implementers. There, I saw tangible proof of growing civil society involvement in programmes aimed at reducing detention through provision of rights-based alternatives.

The examples varied widely and showed that different levels of governmental engagement are possible. We heard from NGOs from Mexico (Asylum Access, Sin Fronteras, SOS Children Villages), Japan (Forum for Refugees), the Bahamas (Red Cross Bahamas) and Jamaica (Red Cross Jamaica).

They included examples of national agencies who refer individuals to NGOs (who operate without any financial support from the government) and examples of alternatives run by NGOs who are fully funded to provide services from public budgets.

The examples also explored various models of the distribution of tasks between the stakeholders: provision of accommodation and case management is most commonly assigned to NGOs, but in some cases civil society would also be entrusted with screening and assessment of those who should not be detained.

A growing appetite for solutions

The promising practices showcased in Mexico align with a growing interest in alternatives to detention in my own European backyard: the European Commission recently strengthened its guidance on alternatives to detention in the returns context. And during the latest Council of Europe conference on child detention hosted in Prague, numerous speakers, while calling for the governments to stop detaining children, also stressed that civil society needs to step in and contribute to the development of effective alternatives to detention.

Despite these strong calls, it still does not come naturally for national governments to involve NGOs in procedures that aim to reduce detention. In Europe, discussion of alternatives to detention has mainly focused on restrictions or conditions placed on individuals (such as reporting, designated residence and bail) which seek to control migrants through coercion – i.e. tasks that cannot and should not be attributed to NGOs.

The IDC’s global comparative research, There are Alternatives, shows that a different, engagement-based approach is more effective in meeting government objectives around compliance and case resolution, yet decision makers fail to fully buy in to this concept. One big challenge has been a lack of examples of engagement-based alternatives from the region. But here also lies an opportunity for NGOs, which are well-placed to build trust and often have the expertise in providing structured support to migrants in the community.

Building evidence for alternatives in Poland

SIP’s No Detention Necessary (NDN) project has been implemented in Poland since June 2017, and it aims to directly respond to this gap by building evidence based on practical implementation.

The project aims to identify a group of ca. 25-30 individuals in return procedures, mostly vulnerable people such as families with children, and provide them with tailored case management, legal and psychological aid to support and empower them to explore all migration outcomes. We want to show that, through this approach, it’s possible to resolve people’s cases in the community without the use of detention.

What makes it different from some other alternatives implemented by NGOs, such as those in Mexico or Australia, is that it is not dependent on governmental engagement, at least not in its initial phase.

We chose this strategy for a reason. First of all, it makes it possible to act now, when the demand for solutions is high, without unnecessary bureaucracy and complicated political negotiations. Also, as the NDN project is a pilot, SIP has the capacity to experiment with tools and methods, to adjust the CAP model to a Polish context. For example, the concept of case management is rarely put into use in social work in Poland, let alone in migration management. SIP is introducing this method, drawing on experiences of other countries and our previous practices of working with migrants.

There are also challenges. The NDN methodology relies heavily on the IDC’s CAP model, however without government involvement some of the conditions of effective alternatives are difficult to fulfil. This is the case with early intervention – without referrals from national agencies in the first phase, an NGO can only rely on its network of contacts and visibility in the migrant community to be able to reach out and support individuals at an earliest stage of their procedures in Poland. It is also not possible for SIP to respond to individuals’ basic needs such as food and housing, therefore we can only work with persons who have their basic needs met through their own efforts or other service providers.

As the project progresses, we aim to engage with different levels of government. Keeping strict rules of collection of information and its recording, followed up by thorough external evaluation, will hopefully enable SIP to build an evidence base that will prove useful for advocacy to reduce detention and expand the use of engagement-based alternatives to detention.

As the project progresses, we aim to engage with different levels of government. Keeping strict rules of collection of information and its recording, followed up by thorough external evaluation, will hopefully enable SIP to build an evidence base that will prove useful for advocacy to reduce detention and expand the use of engagement-based alternatives to detention.

The No Detention Necessary pilot is one of the signs that civil society is ready to take on a more significant role in implementing rights-based alternatives as part of a strategy to reduce immigration detention. SIP is a member of European ATD Network which brings together NGOs in the UK, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Poland and Belgium – each running or exploring pilot alternatives – with the IDC and PICUM, leaders in the field of regional and international advocacy.

Women for Refugee Women Report: We are Still Here

IDC Member organisation, Women for Refugee Women have released a new report: ‘We are Still Here: The continued detention of women seeking asylum in Yarl’s Wood’ which examines the experiences of women detained at Yarl’s Wood immigration detention centre in the UK and assesses the effectiveness of the “Adults at Risk” policy.

IDC Member organisation, Women for Refugee Women have released a new report: ‘We are Still Here: The continued detention of women seeking asylum in Yarl’s Wood’ which examines the experiences of women detained at Yarl’s Wood immigration detention centre in the UK and assesses the effectiveness of the “Adults at Risk” policy.

Following the findings of the Shaw review findings, the UK government introduced the “Adults at Risk” policy in 2016. The policy was intended to reduce the number of vulnerable people detained and a reduction in the duration of detention before removal. The policy recognized that people who are vulnerable or particularly ‘at risk‘ (including survivors of sexual or gender-based violence and pregnant women) may be particularly susceptible to harm in detention and therefore they should normally not be detained.

The 35-page report is based on interviews with 26 women who have claimed asylum and been detained in Yarl’s Wood since the Adults at Risk policy came into effect. The report states that despite what the government promised, the Adults at Risk policy is failing to safeguard and protect survivors of sexual and gender-based violence from harmful immigration detention.

The report makes a number of findings, including:

- Survivors of sexual and gender-based violence are routinely being detained: 22 of the 26 women (85%) interviewed, who had claimed asylum and been detained since the Adults at Risk approach came into effect, reported they were survivors of sexual or other gender-based violence, including domestic violence, forced marriage, female genital mutilation and forced prostitution/trafficking.

- Women who are already vulnerable as a result of sexual and gender-based violence are becoming even more vulnerable in detention: All of the women interviewed aid they were depressed in detention, and 23 of the 26 women (88%) said their mental health had deteriorated while they were detained.

- Survivors of sexual and gender-based violence are being detained for significant periods of time: The lengths of detention for the women interviewed ranged from three days to just under eight months. The vast majority, 23 out of 26 women were in detention for a month or more. Nineteen women were in detention for three months or more.

- Pregnant women are still being detained unnecessarily: Figures Women for Refugee Women have obtained indicate that, under the 72-hour time limit, the number of pregnant women detained has fallen noticeably. But the majority of these women are still being released back into the community to continue with their cases, as was happening before the time limit was introduced: fewer than 20% of pregnant women who are detained are removed from the UK.

The report dedicates a section to alternatives to detention, highlighting that alternatives to detention (such as case management) avoids harm of detention, and promotes the wellbeing of those going through immigration and asylum systems. The report notes there is a wealth of international evidence demonstrating that alternatives to detention are more humane, more effective, and cost less than detention.

The report makes several recommendations, placing emphasis on the need for alternatives to immigration detention. The first recommendation calls on the UK government to work with the voluntary sector to develop and implement alternatives to detention, focused on support and engagement.

Further recommendations include:

- Implement a proactive screening process to ensure that survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, and others who are vulnerable, are being identified before detention

- Implement the stated presumption against the detention of survivors of sexual and gender based violence, and other vulnerable people

- Introduce an absolute exclusion on the detention of pregnant women

- Introduce a 28-day time limit on detention

- Stop detaining people while their asylum claims are in progress

- Implement a monitoring framework and an accountability mechanism for detention reform

IDC Member, Women for Refugee Women is a UK-based organization, which challenges the injustices experienced by women who cross borders to seek safety. Women for Refugee Women work at the grassroots to support and empower women seeking asylum and sharing their experiences through the arts, media, public events and research. Women for Refugee Women also leads the Set Her Free campaign to end the detention of women who seek asylum in the UK.

The IDC is one of many organisations that promote alternatives to detention. The IDC has identified over 250 examples of alternatives from 60 countries and the benefits in restricting the application of detention. The IDC’s handbook There Are Alternatives provides readers with the guidance needed to successfully avoid unnecessary detention and to ensure community options are as effective as possible.

More information:

Women for Refugee Women website

Women for Refugee Women – Set Her Free campaign

Women for Refugee Women – The Way Ahead

Video – ‘We are still here’

International Detention Coalition – There are Alternatives handbook

Ending Child Detention Highlighted at EU Child Rights Forum

The European Forum on the rights of the child is an annual conference organised by the European Commission. It gathers key actors from EU Member States, international organisations, NGOs, Ombudspersons for children, practitioners, academics and EU institutions to promote good practice on the rights of the child.

Held in Brussels November 7 – 8, this year marked the 11th European Forum on the rights of the child, and it focused on Children deprived of their liberty and alternatives to detention.

IDC had a delegation attending, including the coalition’s Advocacy Coordinator Silvia Gomez, Senior Child Rights Advisor Melanie Teff, Youth Advocate Pinar Aksu and Youth Advocate Gholam Hassanpour.

All 193 Member States of the UN have committed to working towards ending child immigration detention in the New York Declaration. Recently a Joint General Comment provided authoritative guidance on the interpretation of the provisions of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and, as such, apply to all State Parties of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and /or the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families. It reinforces and further clarifies that immigration detention is a child rights violation.

More work on developing alternatives urgently needs to be undertaken in the EU, in partnership with civil society. While many positive messages about moving towards ending immigration detention of children were shared at the forum, some states and the European Commission continued to justify immigration detention of children stating that the best interests of children must be balanced with the EU’s interests in migration management.

Melanie Teff, Senior Child Rights Advisor at IDC, moderated the session on immigration detention of children

Resources

Council of Europe Conference on Ending Child Detention

An international conference “Immigration Detention of Children: Coming To A Close?” took place in Prague at the Žofin Palace on 25-26 September hosted by the Czech Chairmanship of the Committee of Ministers.

The conference provided an opportunity to exchange know-how in a number of key areas including existing international human rights standards, views and approaches of regional and universal monitoring, current examples of alternatives to the immigration detention of children and experiences from the field in safeguarding the best interests of the child.

IDC staff at the event included Dr. Robyn Sampson – Research Coordinator and Melanie Teff – Senior Child Rights Advisor, as well as Pinar Aksu – Youth Ambassador for the Global Campaign to End Immigration Detention of Children. IDC Advisory Committee Member Katarzyna Slubik also attended.

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) adopted a resolution in 2014 calling on member states to prohibit the immigration detention of children. It is an opinion that has been echoed by the European Parliament, in line with the CRC Committee Recommendation that immigration detention can never be in the best interests of a child, and States should cease the practice expeditiously. See a summary of normative and policy developments that acknowledge that immigration detention is never in the best interests of a child here.

Despite this clarity, several regional human rights mechanisms in Europe, and States, continue to promote the use of immigration detention for children as provision of last resort, particularly in the returns context.

The conference in Prague provided a space for this important issue to be discussed in depth in the European context.

The Minister of Justice of the Czech Republic, Robert Pelikán provided powerful opening statements about his families history of forced displacement, emphasising that children have no place in detention. The Council of Europe (COE) Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muižnieks, said that “child-friendly detention is an oxymoron” calling on alternatives to detention to be used for all migrant children.

The COE Special Representative of the Secretary General on Migration and Refugees, Thomáš Boček, reinforced the need for engagement-based alternatives in his concluding comments.

Our Youth Ambassador Pinar Aksu presented a very powerful personal story of her detention as a child – see her testimony here.

We were treated as criminals. Our rights as citizens were taken away. As a child at the time, I saw many things that no child should see.

Dr. Robyn Sampson, Research Coordinator of the International Detention Coalition, provided insight into alternatives to detention in Europe. She highlighted the “European Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Network” which links civil society organisations developing case management-based pilot projects in five European countries.

The “European Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Network” links civil society organisations developing case management-based pilot projects in five European countries.

Katarzyna Slubik, the lead advocate at the Association for Legal Intervention based in Poland, presented on the alternative to detention project they are currently developing, which is a member of the European ATD Network. She shared insight into why the project was needed, what services were being offered, and her experience working with civil society with the intention that the pilot can be utilised and expanded by government.

Ben Lewis from the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights provided reiterated that detention as a result of a child’s migration status – or their parent’s migration status – is always a child-rights violation.

The Council of Europe Director General of Human Rights and Rule of Law, Christos Giakoumopoulos, said in his concluding statements that he can only imagine incredibly narrow situations when detention of children could be necessary.

This work also complimented the PACE Committee Parliamentary Campaign to End Immigration Detention of Children, which involves regular briefing sessions with various experts to deepen the knowledge of Parliamentarians on the issue of ending child detention.

Developing alternatives to detention for children provides States with an opportunity to save on costs, improve effectiveness and comply with their international human rights obligations. The IDC has developed a model which highlights the key areas for States to be aware of when developing alternatives to detention for children.

To find out more about alternatives to detention for children, take a look at our online toolkit, featuring interviews with practitioners who are implementing alternatives to detention.

Find out more about alternatives to detention for children via our free online training

The revised Return Handbook: what’s new on immigration detention?

In September, the European Commission published a revised Return Handbook as part of its of the 2015 the European Agenda on Migration. According to the Commission, the review presents next steps towards “a stronger, more effective and fairer EU migration and asylum policy”. Among its key priorities is “a more effective EU policy on return”, with states being encouraged to “streamline their return policies” in line with the March 2017 Commission Recommendation and the Renewed Action Plan on Returns.

While the review itself says little on immigration detention, the Handbook dedicates a large and expanded section to the subject – here we look at what’s new on immigration detention in the revised Handbook.

What is the Return Handbook?

First published in October 2015, the Return Handbook aims to provide guidance to national authorities on standards and procedures for implementing the Return Directive 2008/115/EC. It was published following the rise in the number of refugees and migrants arriving in the region in 2015. While not legally binding, it includes practical commentary and guidance on the implementation of each article of the Directive with examples, extracts from human rights standards and references to relevant ECJ judgements. Over one fifth of the original Handbook was dedicated to immigration detention.

The revised Handbook

The revised return Handbook features additional guidance aimed at achieving the Commission priority of more effective return procedures.

The Commission has been clear that it builds on its Recommendation on Returns in March 2017, which encouraged states to use more and longer immigration detention. This was in a bid to increase return rates, which at an average of 36% in the region were seen as highly unsatisfactory.

The recommendation drew heavy criticism from civil society organisations and the Council of Europe Human Rights Commissioner that it was “likely to lead to human rights violations without furthering other goals, such as facilitating the processing of asylum claims or promoting dignified returns."

An expanded 20-page section in the revised Handbook is dedicated to immigration detention, with commentary on: circumstances justifying detention, review of detention, ending of detention, detention conditions etc.

So what’s new in terms of the Commission’s guidance on immigration detention?

More and longer immigration detention

In line with the Commission’s March 2017 Recommendation on Returns, the revised Handbook includes new guidance for states to “bring detention capacity in line with actual needs,” effectively encouraging states to expand detention capacity. The revised Handbook also recommends that Member States provide for the maximum detention period allowed by the Returns Directive (18 months) whereas this was previously left to the Member States discretion.

The underlying assumption is that more and longer detention will lead to increased returns, whereas the evidence points to the opposite: as the IDC has previously emphasized, international research finds that immigration detention discourages cooperation and decreases the motivation and ability of individuals to contribute to case resolution.

A step backwards: ignoring international standards on child immigration detention

The amended Handbook includes a significant revision regarding child detention. It recommends, in line with the Commission’s March 2017 recommendation, that:

national legislation should not preclude the possibility to place minors in detention, where this is strictly necessary to ensure the execution of a final return decision, and insofar as less coercive measures cannot be applied in effectively in the individual case.

Essentially, this new inclusion encourages Member States to detain child migrants as a measure of last resort to effectuate returns. This clearly goes against a growing body of international law that children should never be detained for migration reasons as it is never in their best interests and that States should therefore “expeditiously and completely cease” the immigration detention of children and families. EU governments seemed positively headed in this direction when they committed to work to end child immigration detention as part of the New York Declaration, adopted by the UN General Assembly on 19 September 2016.

Instead of discouraging Member States from prohibiting child immigration detention, the Commission should provide guidance and support to governments to develop alternatives which allow children’s migration cases to be resolved in the community, in line with their best interests.

Expanded guidance on alternatives to immigration detention

On the positive side, the new Handbook includes an expanded section and additional commentary on alternatives to immigration detention – something that was conspicuously missing from the Commission’s March 2107 Recommendation on Returns.

Newly added guidance includes that:

- Member States should develop and use “a wide range of alternatives to address the situation of different categories of third-country nationals”

- Member States should provide in national law for alternatives to detention that can achieve the same objectives of detention (i.e. prevent absconding, avoid that the third-country national avoids or hampers return) and national authorities should assess whether these are sufficient and effective in the individual case

- UNHCR Options paper 1: Options for governments on care arrangements and alternatives to detention for children and families provides ‘practical examples of good practices on alternatives to detention’

Significantly, the text also now recognizes that as well as “tailored individual coaching, which empowers the returnee to take in hand his/her own return, early engagement and holistic case management focused on case resolution has proven to be successful”.

This is particularly welcome given the strong evidence that the most effective alternatives are based on engagement rather than enforcement: they use holistic and tailored case management to support migrants to engage with immigration processes. However, such alternatives, which often involve civil society to build trust with migrants, have yet to be sufficiently developed in the region. This means that states continue to rely on enforcement-based measures including detention.

Earlier this year, a network of NGOs running case management-based pilot projects in Europe was set up with the aim of building a knowledge base to support governments and other stakeholders to develop further engagement-based alternatives to detention.

Detention of stateless persons

The revised Handbook draws Member States attention to the “specific situations of stateless persons, who may be unable to benefit from consulate assistance by third-countries in view of obtaining a valid identity or travel documents”. It recommends that, in the light of the judgement of the ECJ on Case C-357/09, Kazoev, Member States should make sure that there is a reasonable prospect of removal that justifies imposing or prolonging detention.

Conclusion

The revised Return Handbook was published as part of the Commission’s Mid-term review of the Agenda on Migration, which is the latest in a series of policy documents to prioritise increased return rates in the region. In this context, the revised Handbook includes commentary which, if followed, could give a green light to Member States to use more and longer detention, in line with the Commission’s March 2017 Recommendation on Returns.

At the same time, the revised Handbook provides welcome additional guidance on alternatives to immigration detention – something which was missing from the March 2017 recommendation on returns. Significantly, the Handbook recommends that Member States develop a wider range of alternatives, including “holistic case management focused on case resolution.” This could provide an opportunity to work with governments on developing the kind of alternatives that are effective in resolving people’s cases in the community without the use of detention, thus achieving better outcomes for both governments and the migrants involved.

Further Reading

IDCs analysis of the Return Handbook Version 1

PICUM position paper on EU Return Directive

This article was authored by Anna Sklovsky, completing her communications internship with the International Detention Coalition in 2017.

Does Detention Deter? Developments in Italy

On 2 July, European ministers and the European Commissioner for Migration and Home Affairs held emergency talks in Paris after speculations that the Italian Government was considering closing its ports to boats carrying migrants. During the talks the Ministers of Interior of France, Germany and Italy and the European Commissioner discussed “the challenges posed by the increased migratory flow on the Central Mediterranean route”. In a press release the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi described the situation in Italy as “an unfolding tragedy”, further urging the European Union for greater solidarity with Italy and calling for a “comprehensive regional approach”.

"Italy is playing its part in receiving those rescued and providing asylum to those in need of protection. These efforts must be continued and strengthened. But this cannot be an Italian problem alone." quote from press release Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees

The talks resulted in a joint declaration, the countries expressing strong solidarity with Italy, agreeing to provide increased support to Italy and contribute to ‘stem’ the migratory flow and agree to a number of measures. The declaration indicated support for policies and measures that focus on the origin of the migratory flow specifically collaboration with Libya. Specifically, the declaration makes a commitment to improve the standards of immigration detention centres in Libya, to reinforce border controls in Southern Libya (which may result in more use of detention) and utilise the European Union (EU) returns policy, which may result in more use of immigration detention.

Following the discussion with the European minister and the European Commissioner for Migration and Home Affairs, the European Commission proposed an Action Plan to support Italy, reduce pressure and increase solidarity. The Action Plan set out a series of measures that can be taken by the EU Member States, the Commission and EU Agencies and reiterated the need to support Libya.

"The dire situation in the Mediterranean is neither a new nor a passing reality. We have made enormous progress over the past two and half years towards a genuine EU migration policy but the urgency of the situation now requires us to seriously accelerate our collective work and not leave Italy on its own. The focus of our efforts has to be on solidarity – with those fleeing war and persecution and with our Member States under the most pressure. At the same time, we need to act, in support of Libya, to fight smugglers and enhance border control to reduce the number of people taking hazardous journeys to Europe." – quote from press release European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker

The Action Plan recommended Italy to increase “reception capacity and substantially increasing detention capacity to reach at least 3,000 urgently” and prolong the maximum duration of detention in line with EU law as well as increasing the existing capacity of stationary hotspots. Further recommending improved coordination of Search and Rescue activities (SAR) in Libya; establishment of a fully operational Maritime Rescue and Coordination Centre (MRCC) and set up actions to enhance the capacity of Libyan to control borders.

The use of immigration detention to reduce migratory flow and as a form of deterrence can be ineffective at reducing or deterring irregular migration. Detention is arbitrary and unlawful if applied for the purposes of deterrence (IDC 2015, p. 3). There is no empirical evidence to suggest that the threat of being detained deters irregular migration, or more specifically, discourages persons from seeking asylum. Subsequently restrictive measures can introduce greater risks, rechanneling flows of migrants, forcing migrants to seek assistance from people smugglers and undertake more dangerous journeys.

There are alternatives to detention (ATD) that provide effective, humane and less costly migration management options. Italy is yet to develop ATD as required by EU and International law. The IDC’s handbook There Are Alternatives identifies examples of alternatives to detention being used worldwide.

Find out more

- New Law Prevents Child Detention in Italy Despite Expansion of Detention Centres https://idcoalition.org/news/italy-child-detention-law-change/

- Article Italy boats block - https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/28/italy-considers-closing-its-ports-to-ships-from-libya#img-1

- IDC Detention Deterrence - https://idcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Briefing-Paper_Does-Detention-Deter_April-2015-A4_web.pdf

- UN High Commissioner for Refugees Press release - http://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2017/7/5957c2304/high-commissioner-grandi-urges-solidarity-italy.html

- Interior minister and commissioner statement http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STATEMENT-17-1876_en.htm

- EU Commission press release - http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-1882_en.htm

- Action Plan https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/policies/european-agenda-migration/20170704_action_plan_on_the_central_mediterranean_route_en.pdf

- Alternatives to detention - https://idcoalition.org/alternatives-to-detention/

Future Focus Needed

“Italy alone will need an estimated 1.6 million regular migrants over the next decade to sustain its welfare and pension schemes.” Leaders of The leaders of France, Germany, Italy and Spain in a joint statement.

Fortunately for both the African and European leaders, there are alternatives to a focus on expanding border forces and using detention to stop people moving across frontiers.

“It’s great to see the UNHCR following the lead of African civil society organisations, re-focussing resources to ensure alternatives such as freedom of movement and support services provided through reception centres” said IDC’s Africa and Middle East Coordinator, Junita Calder. “Let’s hope that their government counterparts in both Africa and Europe look at the efficacy of such options and allocate resources to increase their use.”

“It’s great to see the UNHCR following the lead of African civil society organisations, re-focussing resources to ensure alternatives…” Junita Calder, IDC Africa and Middle East Coordinator

New Report: Immigration Detention in Spain

IDC Member, El Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes-España (SJM-E) has now published a short summary in English of their 2016 report on the use of immigration immigration detention in Spain.

It records that immigration detention is being widely used, especially in the case of forced returns.