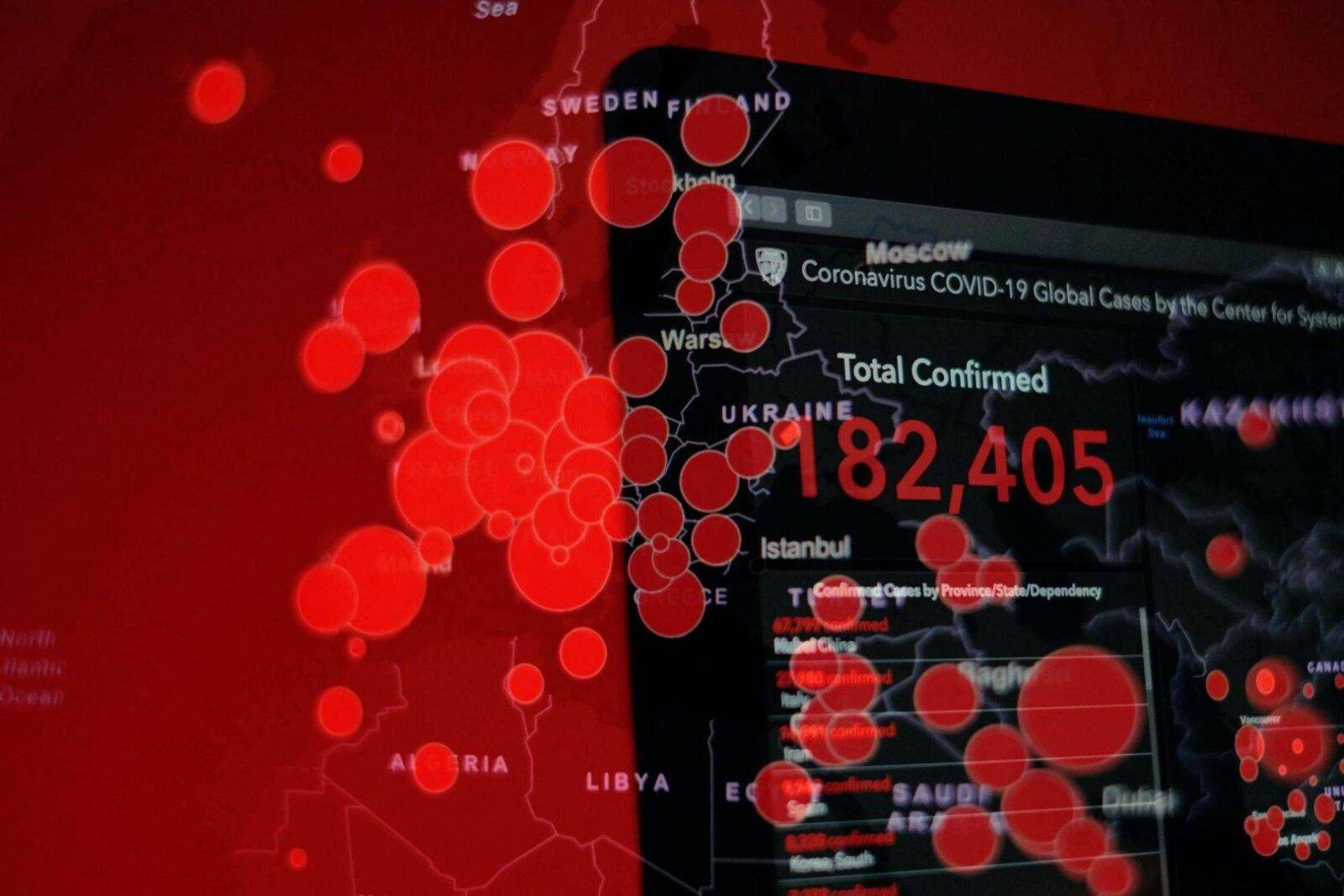

Covid-19 Outbreaks in Malaysia's Detention Centres

In May 2020, Malaysia faced national and global criticism for conducting immigration raids in locked-down areas where Covid-19 clusters had emerged. During these raids, more than 2,000 undocumented migrants, including some refugees and asylum seekers were arrested, among them approximately 100 children.

Within weeks of these raids, Malaysia has now seen a surge of Covid-19 cases (776 cases as of 19 June 2020) in its overcrowded immigration detention facilities, with infections now having been reported in 5 separate detention centres. On 11 June, Malaysia saw its first Covid-19 fatality in immigration detention, a 67 year old man from India, reportedly a stranded tourist, who died in Bukit Jalil immigration detention centre. This detention centre has accounted for over 80% of all Covid-19 cases in immigration detention facilities in Malaysia. On 17 June, it was further reported that a 4 year old boy from Myanmar and his mother, who had also been detained at Bukit Jalil, had tested positive for Covid-19.

The Malaysia government has announced that detainees who test negative for Covid-19 will be deported, while those who test positive will be sent to quarantine centres and treated before deportation. However, given the virus' incubation period, there remains a risk that testing could fail to pick up a positive diagnosis; as a result, further outbreaks of Covid-19 in detention centres are a distinct possibility, as is the risk of deported detainees exporting the virus to another country. Rights groups have also warned of the risk of refoulement, given that asylum seekers have been among those arrested; UNHCR has been denied access to Malaysia's detention centres since August 2019.

Despite these outbreaks in detention centres, the government has refused to impose a moratorium on immigration enforcement activities.

These developments come at a time of a significant rise in xenophobia against refugees and migrants in Malaysia, coupled with increasingly harsh government policies against these groups.

Thai, Jarai, Hmong, Somali & Urdu Resource on Covid-19

Thailand office of HOST International, one of IDC’s active members in Asia-Pacific, has produced a video “What is Covid-19? How to Prevent?” in five languages to target the urban displaced populations. They started with these languages that their primary clients in Thailand speak:

Thai: โควิด-19 คืออะไร? ป้องกันอย่างไร? | What is Covid-19 and How to Prevent?

Jarai/Ede: Nơng do nu Covid-19? Si ngă ciăng răng mgang kman tưp ruă anan? | What is Covid-19? How to Prevent?

Hmong: Covid 19 yog daabtsi? Yuav tiv thaiv tau le caas? | What is Covid-19? How to Prevent?

Somali: Waa maxay Covid-19? Sidee looga hortagaa? | What is Covid-19? How to Prevent?

Urdu: Covid-19 kia hai? Isko kaise roka ya bacha ja sakta hai? | What is Covid-19? How to Prevent?

For more information, please directly contact:

Ms. Katchada Prommachan (Acting country manager) at [email protected]

IDC Asia-Pacific: Covid-19 Impact on Detention

In light of the far-reaching and serious consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic to populations impacted by immigration detention, we recognise that this is an important moment for collective sharing and synergy. As such, the International Detention Coalition and the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network co-hosted a webinar on the impact of Covid-19 on immigration detention in the region on Monday 6th April 2020. More than 20 IDC and APRRN members attended the webinar and shared valuable knowledge and insight. We also received written responses from members and partners who could not attend the webinar.

In this webinar, we had an opportunity to

- discuss key issues that are emerging in the context of immigration detention in respective countries of participants;

- share and reflect on actions taken by organisations, networks and partners since governments started to put in place Covid-19 responses;

- identify positive practices from various countries; and,

- identify gaps, priority needs, and next steps.

Read the Summary document of this webinar.

IDC’s Next Step

Since the webinar, the IDC has developed global Covid-19 Policy Position grounded in our members voices that were expressed through regional webinars. We have also created a dedicated space on our website where we document key developments impacting immigration detention in response to Covid-19 worldwide. We will soon be updating promising ATD practices in the context of Covid-19.

Thailand Screening Paves Way for Better Refugee Protection

On 24 December 2019, the long-awaited National Screening Mechanism (NSM) for refugees was finalised and approved by the Thai Cabinet. The NSM follows the signing of the intergovernmental Memorandum of Understanding on the Determination of Measures and Approaches Alternative to Detention of Children in Immigration Detention Centers in January 2019, which represented a first step towards ending the immigration detention of children in Thailand.

The NSM builds upon Thailand’s continued commitment to improve protection for refugees in Thailand in line with the pledge made by Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha at the September 2016 UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants. Together with the MOU, it provides an opportunity to strengthen the protection of refugees and asylum-seekers In Thailand, particularly freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention.

Thailand has provided refuge to people fleeing war and conflicts from neighbouring countries, particularly those from Myanmar, since 1984. According to UNHCR, the countries currently hosts 93,333 refugees in nine refugee camps along the Thai-Myanmar borders[1]. There are also approximately 5,000 urban refugees and asylum seekers from 40 different countries residing in Thailand[2].

Despite a large number of asylum seekers and refugees in its territory, Thailand has not ratified the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. The Thai Immigration Act, the only law overseeing the entry of non-citizens into its territory, makes no distinction between asylum seekers and undocumented migrants but defines all foreigners without valid documentation as illegal aliens– leaving asylum seekers and refugees vulnerable to arrest and indefinite detention.

Several UN Human Rights mechanisms have demonstrated their concerns over Thailand’s ad hoc approach to refugee policy, and encouraged the country to develop and implement a national legal and institutional framework for the protection of the concerned population. For example, the concluding observations on Thailand’s second periodic report to the Human Rights Committee on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights noted the need for the “speedy establishment of a screening mechanism for asylum seekers”[3] applying for international protection. The approval of NSM is therefore a step forward and should be applauded.

However, there also have been concerns over the contents of this document. While it maps out a plan to establish a screening committee and screening procedures to grant a Protected Person Status to an eligible “alien”, it provides no clear criteria for conditions of application and approval for such Status nor a precise selection procedure for independent expert members for the Screening Committee. Questions around the ambiguity of “relevant agencies” who would provide necessary assistance and support to the people with Protected Person Status also remain.

For now, 180 days were given to develop a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) under the NSM before its implementation following the date of its official publication in the Government Gazette on 25th December 2019. IDC members and partners in Thailand are working collaboratively with the relevant government agencies to ensure that the SOP addresses the identified concerns and guarantees the necessary protections for refugees.

[1]Total verified refugee population as of 31st Dec 2019. https://www.unhcr.or.th/sites/default/files/u11/Refugee%20Population%20Overview_December%202019_0.pdf. (Accessed on 3rd Feb 2020)

[2] https://www.unhcr.or.th/en/about/thailand. (Accessed on 3rd Feb 2020)

[3] Human Rights Committee (2017) Para. 28 of Concluding observations. CCPR/C/THA/CO/2. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CCPR/C/THA/CO/2&Lang=En (Accessed on 3rd Feb 2020)

Regional Roundtable on ATD in Bangkok

International Detention Coalition (IDC) recently co-hosted a closed-door roundtable on alternative care arrangements for children in the context of international migration in the Asia Pacific with the Department of Children and Youth under the Thai Ministry of Social Development and Human Security and Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration (ADFM). The roundtable took place on 22 November 2019 in Centra by Centara Government Complex Hotel and Convention Centre, Bangkok, Thailand.

The roundtable brought together representatives from implementing and policy agencies within government from Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, as well as non-governmental agencies and international organizations in the region for constructive discussion on developing alternative care mechanisms for children and their families in the context of migration. Participants exchanged positive practices and latest developments in alternative care arrangements for children in their national contexts, while identifying common challenges and opportunities that can support the development of an ongoing regional program of engagement, learning and action towards ending child immigration detention in the region.

More information about the roundtable, including the agenda, participant list and background paper can be found here.

The ADFM Secretariat also recently posted about the event, including a brief summary of ideas that emerged from the roundtable. The post can be found here.

VIDEO: Community Placement & Case Management by SUKA Society

SUKA Society, IDC member organisation in Malaysia, is implementing a holistic Community Placement and Case Management (CPCM) programme that specifically looks into the protection concerns of unaccompanied and separated children in the country. This programme is a part of their initiative to advocate for alternatives to detention of children.

The video provides a brief introduction to who is an unaccompanied and separated child and the case management process undertaken by SUKA.

Watch here:

How Change Happened in Thailand

Interview compiled by Vivienne Chew

Asia Pacific Regional Coordinator, International Detention Coalition

On 21 January 2019, following years of sustained and strategic advocacy by the IDC, its members and other stakeholders, the Thai government announced it had established new internal government procedures to release children and their mothers from immigration detention to community-based alternatives. This remarkable development now positions Thailand as a leader in the region on this issue. In the aftermath of the MOU signing, Puttanee Kangkun, Senior Human Rights Specialist at IDC member organisation Fortify Rights reflects on what the change means and how it happened.

How important a development is the MOU for refugee and migrant children in Thailand?

It’s really significant because it’s concrete and solid. There was very little protection for refugees or asylum seekers before. But the Prime Minister made a speech at the New York Summit in 2016 and publicly affirmed the need to end child detention. We saw that as a big step then, and this as an even bigger step now.

What are some of the key factors and events that you believe led to the government making the decision to draft and sign the MOU?

This is very significant for Thai people, and those of us who work on refugee issues here. It happened through a combination of efforts over years of advocacy work. The global campaign work on child detention helped to build a global trend and global norm that influenced the Thai government. Especially in the past couple of years, there has been a change of perspective within the government on these issues, as well as a change of policies towards refugees. More awareness was developed in the government of the UN treaties, issues of detention, and the need to report on global standards and regulations. This was an international pressure, because Thailand wants to be a good member of the international community and global economy.

At the same time, within the country, there has been a movement of local civil society organisations, people and activists. They are echoing the voices of refugees and refugee communities. Sometimes they criticised the government for their policies, which put pressure on officials. The Rohingya crisis also brought more attention to the issue, and an urgent need to address these issues publicly. There became an understanding in Thai society and the government that we cannot push people under the rug anymore. It’s up to our society to do better.

Do you think civil society played an important role? How? What were some of the key things that civil society did?

Children are always a key concern for Thai society. People support work to help children, it’s a very sensitive issue for Thai people and culture. Civil society organisations in Thailand worked to develop the understanding that this issue is about protection for all children, not just Thai children. It was useful to highlight this strong underlying value, because it overrides issues of immigration status. Thai society welcomes policies that protect children, and this support is good for the government. Eventually officials said that their child protection laws should cover all children, not just Thai children. And then from mid 2017, they have been removing children from detention and placing them in foster care.

The scorecard* also helped us to engage with government agencies as part of a process. We formed a group of organisations to work on this issue together in Thailand - including Coalition for the Rights of Stateless Persons and Refugees (CRSP), Asylum Access Thailand (AAT), Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network (APRRN), Save the Children Thailand, Fortify Rights and others. The scorecard has become an educational tool as well. It helps civil society organisations uncover the elements we need to look at more closely. We used it not to criticise, but to strategise together. Even with the value and principles of child rights, the government still needed education and capacity building to support children outside of detention and develop alternatives. There was no child care management for migrant and refugee children in urban settings before.

This intersection of child rights and refugee rights is very new in Thailand. We have now engaged organisations that work on child rights issues more broadly, and influenced their inclusion of refugee children in their work. They have also taught us to include the rights of children more clearly in our overall refugee rights work. The exchange of expertise within our networks was very important for developing knowledge to address this specific issue of child immigration detention. Our coalition has been meeting almost every month to strategise on this, and we are lucky to have a very engaged and collaborative group of organisations involved.

There are both Thai-based organisations involved, and external global and regional organisations. I believe you need both. External organisations can push and provide global frameworks that can influence our governments, but you need local groups to actualise and contextualise the policies, and also monitor the implementation of policies. You need local actors to make change happen, and continue long-term engagement with their own government. It’s very important for people and their own governments to be able to work together, with the support of the international community.

What’s next?

Moving forward we need more models for alternatives to detention. We are developing more community placement models now. This knowledge is new, and we need to continue to build it and sustain it. We also need to carefully monitor the implementation of this MOU, and be sure that family unity and reunification are part of it.

*The scorecard is part of the NextGen Index, a project of the International Detention Coalition. The scorecard is a comparative tool used to assess States on their progress towards ending child immigration detention. The Index uses a standard scoring framework to identify the key factors that ensure national migration management systems are sensitive to the needs of children, and avoid detention. More on the 2018 version of the NextGen Index here.

IMPORTANT: Call for Inputs on Immigration Detention

WHAT: The Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families has decided to elaborate General Comment No. 5 on Migrants’ Rights to Liberty and Freedom from Arbitrary Detention. This is a critical opportunity to provide input and feedback on fundamental human rights issues. The Committee invites all stakeholders to provide inputs to this initiative through a questionnaire by 1 April 2019. The concept note and questionnaire are available in English and Spanish HERE.

HOW: Please send responses electronically in Word format to [email protected] with subject line “Submission for General Comment on Migrants’ Right to Liberty.” Submissions should not exceed 10 pages. Written submissions will not be translated and should preferably be submitted in English, however submissions in French and Spanish will also be accepted. All submissions will be posted on the webpage of the Committee unless explicitly indicated to the contrary.

Any questions should be addressed to the Secretary of the Committee, Mr. Luc Mubiala, at [email protected].

If you would like to inquire about being connected to other organisations in your region also working on responses, please contact the following IDC regional offices:

Americas [email protected]

Europe [email protected]

Africa [email protected]

Middle East & North Africa [email protected]

Asia Pacific [email protected]

Seven Rohingya Children Ordered Released In Malaysia

A Malaysian court ordered for the release of seven Rohingya children detained in an immigration detention centre in Malaysia into a NGO shelter, following an application for habeas corpus to challenge their detention brought by their lawyers.

In this landmark judgment, the court recognised the viability of alternatives for children in Malaysia, and for the first time, explicitly referred to the rights of the CRC being applicable to children in immigration detention.

While the High Court judge ruled that the detention order on the children was valid as they were non-citizens who did not have the approval to enter and remain in Malaysia, the judge also noted the requirement for “appropriate protection and humanitarian assistance” as set out in Article 22 of the Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC).

“Without need for further elaboration, this court is of the view that, continued detention of the applicants at the Belantik detention camp, has violated the children’s rights under CRC and also the Child Act 2001 that also recognises the right to protection and assistance in all situation to children regardless of race, colour, gender, language, religion and so on,” the judge said in the written decision.

The court ordered that the children be placed in a shelter that can provide for the children’s welfare, and was of the view that Chow Kit Foundation, a local shelter based in Kuala Lumpur, would be able to ensure that these benefits would be available to the children.

Each child was released with a bail of RM500 ($120). The court went on to hold that the safety and welfare of the children at the shelter should also be assured during the 'detention on them' and they should be made ‘available’ at all times needed by the authorities for any further 'action on them,' including to be present in court to answer any charges if there are such charges. Subsequently, the court made an additional order that the children would be released immediately to the care of UNHCR, as part of immigration's further action.

Further News Coverage: Judge Sends Seven Rohingya Children from Kedah Immigration Detention to KL Shelter

Indonesia Theory of Change Workshop

On 26th and 27th of June, the IDC brought together 15 participants from civil society organizations and United Nations agencies in Indonesia to develop a theory of change for ending child immigration detention. Theory of change is a methodology for planning, participation and evaluation that is used to promote social change.

The workshop held in Jakarta, was led by an experienced theory of change facilitator from DSIL Global.

Over a period of two days, participants came together to identify a common long-term goal as well as specific short-term, medium-term and long-term outcomes necessary to bring an end to immigration detention of children and their families, and to develop effective community-based alternatives.

Through facilitated discussion, participants also furthered their common understanding existing initiatives, policies and opportunities, strengthened their knowledge of each organizations work, and identified gaps and challenges in national advocacy.

“this workshop was the first time that a broad range of stakeholders have came together to develop a common vision and cohesive long-term strategy…”

In Indonesia, a Presidential Decree signed in January 2017 affirmed, amongst other things, the availability of alternatives to detention for refugees. However, the language of the Decree is broad and ambiguous, and implementation remains challenging.

Although groups have been engaged on advocacy and service provision for children impacted by immigration detention for several years now, this workshop was the first time that a broad range of stakeholders have came together to develop a common vision and cohesive long-term strategy that strengthen alternatives to detention for children, including through the implementation of the Presidential Decree.

Following this workshop, participants will further refine the theory of change, clarify assumptions, and begin identifying ways to implement interventions and activities to reach the common goal.

This workshop follows similar workshops organized by IDC in Malaysia and Thailand in February and May this year respectively.