Thailand: Theory of Change Workshop

Bangkok Workshop

On 16th and 17th of May, the IDC brought together various stakeholders in Thailand to develop a national strategy for ending child immigration detention, built upon a theory of change.

Theory of change is a methodology for planning, participation and evaluation that is used to promote social change.

The workshop, led by an experienced theory of change facilitator, was held in Bangkok and was attended by close to 20 participants from civil society and United Nations agencies.

Over a period of two days, participants came together to identify a common long-term strategy, as well as specific intermediate outcomes needed to bring an end to immigration detention of children and their families, and to develop effective community-based alternatives. Participants also identified existing opportunities, gaps and challenges in national advocacy, as well as areas for intervention and capacity-building to achieve those aims.

In Thailand, groups have been engaged on advocacy and service provision for children impacted by immigration detention for several years now, however this is the first time that a broad range of stakeholders have came together to try to develop a common vision and cohesive long-term strategy to end immigration detention of children.

Following this workshop, participants will further refine the theory of change, clarify assumptions, and begin identifying ways to implement and evaluate interventions.

IDC organized a similar workshop in Malaysia at the end of February, and will be organizing one in Indonesia in the coming months.

Detention in Malaysia Criticised by CEDAW Committee

The observations were released on 12th March 2018, following the Malaysian government’s review in February 2018 with respect to its compliance with the CEDAW in the 69th session of the CEDAW Committee.

The Committee commended the Malaysian Government’s involvement in the dialogue after a 12 year lapse. However the Committee expressed disappointment with the lack of meaningful progress on gender equality in its report.

Arbitrary detention was raised as a point of concern, as well as sexual and gender based violence and the lack of access to justice and healthcare for migrant, refugee, asylum-seeker and stateless women and girls in detention. Notably, the Committee highlighted their concern that “the lack of legal and administrative framework to protect and regularize the status of asylum-seekers and refugees in the State party exposes asylum-seeking and refugee women and girls to a range of human rights violations, including arbitrary arrest and detention, exploitation, sexual and gender-based violence, including in detention centres.”

CEDAW is one of only three UN human rights treaties ratified by Malaysia. Gender inequality continues to exist despite the constitutional guarantee of equality in Article 8(2) of the Federal Constitution - disproportionately impacting refugee, asylum-seeking, stateless and migrant populations. Through CEDAW Committee’s General recommendation No. 32 on the gender-related dimensions of refugee status, asylum, nationality and statelessness of women (‘General Recommendation 32’), asylum-seeking, stateless and refugee women fall within the scope of CEDAW.

Malaysia is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, or its 1967 Protocol, and has no framework in place to identify and protect asylum seekers and refugees in Malaysia. Under the Immigration Act 1959/63, asylum seekers and refugees are not distinguished from undocumented migrants (of which there are some estimated 2- 4 million currently in Malaysia).

At the end of December 2017, there were 152,320 asylum seekers and refugees registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Malaysia, of which approximately 34% are women. According to the Government’s Annex to Reply to the List of Issues, as of September 2017, there were a total of 1,814 women in immigration detention centers across Malaysia, including 128 girls.

Although the government confirmed that refugee, asylum-seeking and stateless women who are in detention are released after UNHCR verifies that they qualify for international protection, the Committee expressed their grave concern at recent reports of refoulement of individuals, including women, who were registered with the UNHCR. The Committee also raised its concern about a Government directive which requires public hospitals to refer undocumented asylum-seekers and migrants who seek medical attention to the Immigration Department - effectively deterring them from accessing essential health care services due to fear of arrest and detention.

In the recommendations in its Concluding Observations, the Committee highlighted the need to “establish alternatives to detention for asylum-seeking and refugee women and girls, and in the meantime take concrete measures to ensure that detained women and girls have access to adequate hygiene facilities and goods and are protected from all forms of gender-based violence, including by ensuring that all complaints are effectively investigated, perpetrators are prosecuted and adequately punished, and victims are provided effective remedies”.

In addition, the recommendations the Committee made in relation to women and girls impacted by immigration detention include:

- Identify and address the specific obstacles faced by undocumented women, women held in immigration detention centres, and asylum-seeking and refugee women to ensure that they have access to justice and recourse to effective remedies;

- Immediately repeal the directive requiring public hospitals to refer undocumented asylum-seekers and migrants to the Immigration Department;

- Adopt national asylum and refugee legislation and procedures which ensures that the specific needs of women and girls are addressed;

- Codify and fully respect the principle of non-refoulement and ensure that no individual who is registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees is deported;

- Ensure full access to asylum procedures for persons seeking asylum, including women and girls; and

- Ensure that a formal victim identification procedure to promptly identify and refer victims of trafficking to appropriate services and protection includes an assessment of their needs for international protection

As a follow up measure, the CEDAW Committee has requested that the Malaysian government provide, within the next two years, written information on the steps taken to implement recommendations related to refugee and asylum-seeking women.

Other relevant documents on the session, including State Party reports, and shadow reports by the National Human Rights Institution and civil society organisations can be found here.

Malaysia Strategy Workshop

At the end of February, IDC members and partners in Malaysia came together for a two-day national workshop aiming to develop a collective theory of change.

Theory of change is a methodology for planning, participation and evaluation that is used to promote social change.

Various groups have been advocating for alternatives to immigration detention for children in Malaysia since 2012. However, advocacy initiatives have tended to focus on relatively short-term goals and emerging opportunities.

The workshop provided a space for discussion about longer-term goals and strategies, as well as ways in which to respond to challenges, gaps and risks related to advocacy for, and implementation of alternatives.

Regional Roundtable on Judicial Engagement for Southeast Asia

On 6-7 December 2017, the IDC along with UNHCR and APRRN, co-hosted a regional roundtable on judicial engagement in Kuala Lumpur.

Attended by lawyers, and representatives from NGO and UNHCR offices from Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, the main objective of the roundtable was to build capacity and raise awareness among the legal community of international human rights standards and refugee law, with a special focus on immigration detention.

Participants spent 2 days sharing successful strategies, precedents and good practices in engaging the judiciary on immigration detention issues and challenging, through strategic litigation, the immigration detention of children and others in situations of vulnerability or risk.

Migration in Malaysia: Civil Society Consultations

The IDC, along with UNHCR Malaysia, the National Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM), and the Malaysian Representative to the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) organised a solutions-orientated consultation with key civil society stakeholders to discuss immigration detention and forced displacement in Malaysia.

The consultations, which took place on 5 February 2018, were attended by 85 participants from 35 organisations including refugee leaders, academics, think tanks, Commissioners and staff from SUHAKAM, and representatives from UNHCR and other UN agencies.

The consultations focused on examining current laws and policies relevant to forced migrants in Malaysia, as well as identifying positive examples of strategies for engaging government around alternatives to detention for vulnerable groups and improvements to detention conditions.

The consultations concluded with a group work session in which participants brainstormed on key issues and recommendations for government on developing alternatives to detention for vulnerable groups, addressing gaps and challenges in the arrest and detention process, and improving conditions of detention in Malaysia.

Raising the plight of migrant children in Asia Pacific

Migrant Children in Asia Pacific - Joint side event coordinated by IDC with UNICEF and Save the Children alongside the ESCAP Global Compact preparatory meeting. Speaking: Vivienne Chew, IDC Asia Pacific Regional Coordinator

On the 6th of November, The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) held a Preparatory Meeting for the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM). The Preparatory Meeting was one of a series of regional consultations organized as part of the consultation phase to inform the development of the GCM. The Preparatory Meeting aimed to provide a forum to identify key migration issues, challenges and priorities for the Asia-Pacific region, and to generate a set of conclusions that could serve as regional input into the global stocktaking meeting due to be held in Mexico in December 2017.

During the Preparatory Meeting, the issue of child immigration detention was raised by several participants who drew attention to the commitment made by member states in para 33 of the New York Declaration to “pursue alternatives to detention” and to “work towards the ending of this practice [of child immigration detention”]. These concerns were noted by the Chair, whose statement records that “[i]n line with the New York Declaration, some representatives noted the need to strengthen alternatives to detention of children. They also recognized the efforts of several States to move towards ending immigration detention of children.” Further details of the Preparatory Meeting including the Chair’s summary, agenda, key thematic areas, list of participants and statements made by member states and other participants are available online

The IDC, in partnership with UNICEF and Save the Children, organized a side-event at the Preparatory Meeting titled “Migrant Children in Asia Pacific: how to address their needs and uphold their rights”. The event focused on how the GCM can ensure that the rights of migrant children are upheld. The event aimed to tackle the challenges faced by migrant children in Asia‐Pacific, particularly focusing on care and protection, access to services and child immigration detention, as well as showcase good practice examples from the Asia Pacific region. According to a UN statistic (2015), nearly 12 million of the world’s international child migrants live in Asia. It is therefore vital that Asian nations, civil society, and other stakeholders facilitate dialogue towards securing the rights for these children.

The IDC’s Asia-Pacific Regional Coordinator Vivienne Chew drew attention to the issue of child immigration detention as highly detrimental to the rights and well-being of child migrants. In South-East Asia alone, research shows that children, including babies, are being held in detention cells 24 hours a day, alongside dozens of unrelated adults, and are frequently separated from family members. Such detention leads to a wide range of negative physical, and psychological impacts including PTSD, major depression, self-harming, suicidal ideations, nightmares and night terrors. States detain children for reasons that are quite avoidable, such as to conduct routine health and identity screening, to maintain family unity, or to facilitate engagement with ongoing migration procedures. Sometimes children are detained because of a failure to properly conduct age assessments, or due to a lack of robust child screening and identification processes. Governments are increasingly searching for ways to end this harmful practice and to develop child-sensitive, community-based alternatives to detention.

This growing momentum is clearly reflected in Article 33 of the New York Declaration. The GCM provides states with a fundamental opportunity to build upon the commitments in the NYD to work towards ending the immigration detention of children and to pursue alternatives to immigration detention. It is important however, that the GCM provides a set of concrete targets and indicators for operationalizing these commitments, such as those suggested in the Children’s Rights in the Global Compacts: Recommendations for protecting, promoting and implementing the human rights of children on the move in the proposed Global Compacts.

Urgent Need for No Child Detention Policy in Thailand

The immigration detention of children continues to be a pressing concern in Thailand. On November 2nd, Fortify Rights reported that a young Rohingya girl named Zainab Bi Bi had died after spending over three years in immigration detention facilities and government-run shelters in Thailand.

According to Fortify Rights, the 16-year old Rohingya refugee had reportedly fainted and bled from her nose and ears on 27th October while being detained at the Sadao Immigration detention centre (Sadao). She died six days later. Zainab had been trafficked from Myanmar to Thailand; in 2015 the Thai authorities transferred her to Sadao from a shelter run by the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security. Zainab received treatment several times for her affliction during the months preceding her death.

Fortify Rights have documented deplorable conditions within Thailand’s IDC’s including at Sadao. Detainees at Sadao have told Fortify Rights that they were confined indoors 24-hours a day in overcrowded, unsanitary cells without access to adequate hygiene amenities, adequate food, physical exercise, or appropriate medical treatment. This immigration detention centre was clearly not a safe or appropriate place for Zainab.

Zainab’s death comes after a government crackdown beginning in October which saw numerous asylum seekers from Pakistan and Somalia arrested and detained. On October 30th, Thai police raided homes in Bangkok, arresting 22 Pakistani asylum seekers, including nine women and six children under the age of 10. These asylum seekers were detained overnight at the Suan Phlu Immigration Detention Centre (Suan Phlu). The following day, the police released the children to parents or relatives in their community and brought the adults to court. The Taling Chan Provincial Court charged 15 of the adults for overstaying their visas and one adult with unauthorized entry into the country. Their applications for bail are currently pending.

Zainab’s death comes after a government crackdown beginning in October which saw numerous asylum seekers from Pakistan and Somalia arrested and detained. On October 30th, Thai police raided homes in Bangkok, arresting 22 Pakistani asylum seekers, including nine women and six children under the age of 10. These asylum seekers were detained overnight at the Suan Phlu Immigration Detention Centre (Suan Phlu). The following day, the police released the children to parents or relatives in their community and brought the adults to court. The Taling Chan Provincial Court charged 15 of the adults for overstaying their visas and one adult with unauthorized entry into the country. Their applications for bail are currently pending.

The authorities released four children, including an infant, and five adults on the same day. The other 12 asylum seekers, including four unaccompanied children, were sent to the Suan Phlu. On November 2nd, the Phra Nakhon Nuea Court fined the eight adults for alleged violations of the Immigration act and returned them to the Suan Phlu, where they await bail. As of November 20th, three of the four unaccompanied children have been released, however one remains in detention.

On October 21st, Fortify Rights documented the arrest and detainment of an 11-year-old boy, whose mother (not detained) feared for his safety. The Somalian mother states that “I witnessed the killing of my husband and the rest of my children (back in Somalia), but I managed to survive. My son is the last of my family. He is everything to me.”

The continued arrest and detainment of children is at odds with statements made by the Thai Prime Minister at the Obama Summit before the New York Declaration. Later in November 2016, in its reply to the list of issues raised during the Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review, the Thai government implicitly reinforced that it does not intend to detain ‘children, women and sick people.’ Subsequently in early 2017, the government reassured the Human Rights Committee that Thailand has a ‘no child detention policy.’ This statement coincided with a Cabinet resolution in January 2017 approving, in principle, a proposal to develop and implement a screening mechanism for undocumented immigrants and refugees.

The case of Zainab and recent raids show that despite such statements by the Thai government, child asylum seekers and refugees continue to be arrested and detained indefinitely in immigration detention centres across Thailand. International research has shown that even short periods of detention are harmful to a child’s psychological and physical wellbeing and compromise their cognitive development. Thailand is a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which provides minimum standards to ensure the protection, survival, and development of all children without discrimination. The CRC Committee has provided authoritative guidance that children should not be detained on the basis of their or their parent's migration status, and States should expeditiously cease the practice.

However, there are positive developments. The Thai government is working with civil society to develop alternative care arrangements in the community for unaccompanied children, as well as children and their mothers. Such efforts should be continued, and alternatives developed that respect family unity as well as avoid the institutionalization in shelters that may act as alternative forms of detention. Thailand must also adhere to its child-specific legislation (such as the Child Protection Act) which could have significant positive impacts on child asylum seekers and refugees. Government Ministries should also treat those under 18-years-old first and foremost as ‘children’ and thereby include them within the purview of such legislation.

Australia Policy Recommendation to End Child Detention

Alliance calls on Australian Government to lead the way in protecting displaced children.

The IDC is one of a coalition of NGOs calling on the Australian Government to lead the way in protecting child refugees and migrants, as two ground-breaking compacts are discussed at the United Nations General Assembly this week.

Australian members of the Initiative for Child Rights in the Global Compacts – including Save the Children, UNICEF Australia, World Vision, International Detention Coalition, the Multicultural Youth Advocacy Network and ISS Australia – today released a policy brief outlining key recommendations.

The recommendations are concrete actions based on global commitments made in the UN’s 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants, and include a ban on immigration detention of children.

The call comes as more than 400,000 people flee from Myanmar to Bangladesh in one of our region’s largest reported population displacements in recent years; and migrants continue to drown in their thousands in the Mediterranean.

Among other policy changes, the alliance is calling for the government to:

- Significantly increase Australia’s annual humanitarian intake to offer protection to more people, including children.

- Ban immigration detention of children; ensure families are kept together wherever possible, and migrant children have access to child protection services.

- Increase multi-year funding commitments targeted towards quality education for displaced children, including in host communities.

The Plight of Muslim Rohingya

The plight of Muslim Rohingya: What does their future hold?

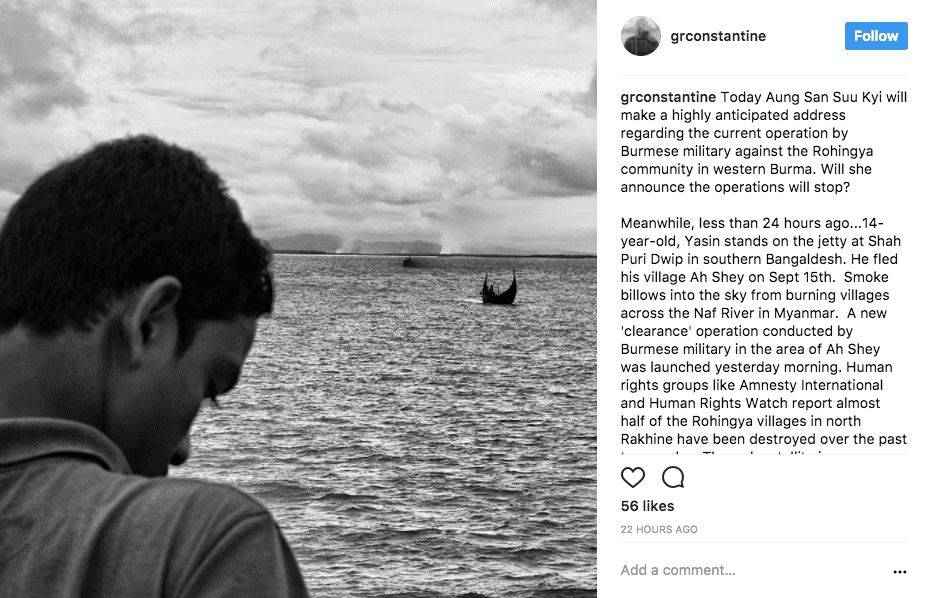

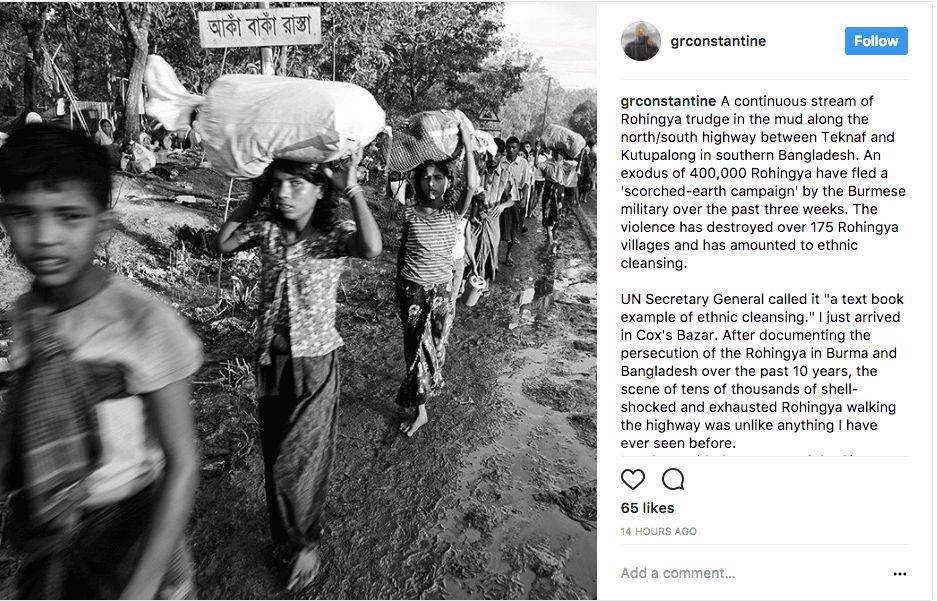

On August 25th The Myanmar government undertook a horrific crackdown on the minority Muslim Rohingya living in the Rakhine state of west Myanmar. Arakan Salvation Army militants coordinated numerous attacks on 30 Myanmar police outposts and an army base. In response, the Myanmar army and other armed ethnic groups hostile to the Rohingya initiated a string of mass atrocities including; attacks on villages, burning of homes, and widespread reports of rape. As a product, there has been mass exodus- over 300,000 currently reported Rohingya fleeing to nearby borders in Bangladesh

Photo: Greg Constantine

What’s the background?

The Rohingya are a Muslim ethnic minority living in the Rakhine state of West Myanmar. The Myanmar nationality law (1982) does not legally recognize Rohingya as citizens, and has historically subjected this ethnic group to discrimination, abuse and neglect. The Myanmar government insists that all Rohingya are immigrants from Bangladesh, despite living in the Rakhine state for generations. In effect, the Rohingya are subject to marriage and child-birth restrictions, statelessness, and have limited access to health care, schools, jobs, and freedom of movement.

In 2012, following the alleged gang rape of an ethnic Rakhine woman by three Muslim Rohingya males, tensions between Muslim Rohingya and the predominantly Buddhist Rakhine population erupted. Targeted attacks and rioting forced tens of thousands of Rohingya to flee into nearby displacement camps.

IDC member Fortify Rights exposed local orders and internal government documents in 2014, revealing severe restrictions on freedom of movement, marriage, childbirth, and other aspects of daily life for more than one million Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State. The government continues to confine more than 120,000 people—mostly Rohingya survivors of 2012 violence—to 38 internment camps in eight townships in Rakhine State.

On August 23rd, 2016, Myanmar state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi established a nine- member advisory commission on the Rakhine state. The aim of the committee was to address underdevelopment and humanitarian issues surrounding Muslim Rohingya.

In October 2016, Rohingya militants attacked Myanmar police outposts in the North of Myanmar’s Rakhine state in response to the continued systematic persecution of Muslim Rohingya. In response, the Myanmar army launched a massive crackdown on the entire Rohingya population. Amnesty International have documented widespread extensive and horrific human rights abuses on Muslim Rohingya as a result. Unlawful killings, arbitrary arrests, rape and sexual assault of women and girls, and the burning of more than 1,200 buildings, including schools and mosques were included. This crackdown displaced more than 80,000 Rohingya Muslims and sent them fleeing into nearby Bangladesh.

Following the Myanmar Army’s crackdown in northern Rakhine State in October, the U.N. Human Rights Council passed a landmark resolution on March 24 ordering an independent, international Fact-Finding Mission to investigate human rights violations and abuses in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. The President of the Human Rights Council appointed three experts to lead the mission.

IDC member Fortify Rights recommended that the Fact-Finding Mission focus on human rights violations by state and non-state actors in Rakhine, Kachin, and Shan states. The Government of Myanmar “disassociated” itself from the resolution. Suu Kyi explained that her government would not cooperate with the Mission. The Myanmar military and Suu Kyi’s offices have routinely denied allegations of serious human rights violations in Rakhine State since October 2016. On August 6, another commission appointed by Suu Kyi and led by Vice President Myint Swe dismissed allegations of serious human rights violations in Maungdaw Township since October.

Latest developments

IDC member Human Rights Watch has obtained satellite data and images that are consistent with widespread burnings in northern Rakhine State, encompassing the townships of Rathedaung, Buthidaung, and Maungdaw. To date, Human Rights Watch has found 21 unique locations where heat sensing technology on satellites identified significant, large fires.

Matthew Smith, the Chief Executive Officer for Fortify Rights has stated that “Mass atrocity crimes are continuing. The civilian government and military need to do everything in their power to immediately prevent more attacks.” Fortify Rights interviewed 24 survivors and eyewitnesses of attacks in the last week from 17 villages in the three townships of northern Rakhine State—Maungdaw, Buthidaung, and Rathedaung. Survivors and eyewitnesses described mass killings and arson attacks by the Myanmar Army, Myanmar Police Force, Lon Tein (“security guards”) riot police, and local armed-civilians.

HRW argues that Suu Kyi's inflammatory propaganda is fueling anti-Rohingya and anti-aid-worker sentiment at a time when she should be doing everything in her power to instill calm, promote human rights, and open more humanitarian space. “Rather than deal with ongoing atrocities, the Suu Kyi government has tried to hide behind the Advisory Commission,” said Matthew Smith “The Commission responded with concrete recommendations to end violations, and the government should act on them without delay.”

Between the Annan Commission, U.N. fact finders, and Myanmar’s own civil society, the government has an opportunity make real progress in ending and remedying atrocities,” said Matthew Smith. “Some officials are looking to sweep Rakhine under the rug. The military and civilian authorities should cooperate with international efforts to establish the facts and hold perpetrators accountable. There’s no other way forward.”

Bangladesh: Despite being the main destination for Rohingya, resources are stretching thin

Sharing a border with Myanmar, Bangladesh has remained the main destination for Rohingya fleeing violent persecution. Since August 23rd however, Bangladesh has stressed that it cannot cope; lacking the food, water and shelter resources necessary to absorb the massive influx of Rohingya. In effect, as the crisis continues, Bangladesh has become less accommodative of Rohingya refugees. There are at least 400,000 Rohingya living in squalid camps already in Bangladesh, and the latest UN figures have estimated around 409,000 have recently entered Bangladesh from Myanmar since violence erupted. This has led to Bangladeshi border authorities to deny the entry of Rohingya into Bangladesh where they can, and confine them to the Cox’s Bazaar area near the border. This report is supported by numerous other reports of authorities leaving thousands stranded on the border in makeshift camps.

Bangladesh is aware that is in the midst of an intense humanitarian crisis, and isn’t equipped to deal with the influx of refugees. “We are stopping them wherever we can, but there are areas where we can’t stop them because of the nature of the border; forests, hills,” said H.T. Imam, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s political adviser. In effect, Bangladesh has given serious consideration to relocate Rohingya to an Island named Thengar Char. Makeshift camps in Cox’s Bazar in south-east Bangladesh have grown so rapidly since the crisis, they have run out of space.

Malaysia and Thailand: Prepared to shelter Rohingya, but immigration detention seems likely

Zulkifli Abu Bakar, the director-general of the Malaysia Maritime Enforcement Agency has claimed that it is ready and willing to provide shelter for Muslim Rohingya fleeing violence and persecution in Myanmar. As a Muslim-majority nation already home to more than 100,000 Rohingya refugees, Malaysia will probably house the new arrivals in immigration detention centers. Illegal entry and stay policy in Malaysia is criminalized, and immigration detention is where foreigners without documents are typically held.

At the same time, a protest on 30 August by the Rohingya against recent events in Myanmar saw more than a hundred Rohingya arrested and detained, with some subsequently charged for entering into Malaysia without valid travel documents. In response, hundreds of ethnic Rohingya protestors have gathered in the Malaysian capital of Kuala Lumpur (Wednesday Aug 30) demanding an end to the bloodshed in Rakhine.

Thailand, navy spokesman Chumpol Lumpiganon said the government and the navy are preparing to deal with hundreds of Rohingya migrants who flee violence by boats and often drift into Thai waters. The Third Fleet, which oversees the Andaman Sea, and the navy operation centre, has been put on alert along the Andaman coast from Ranong to Satun. The navy will provide assistance to the migrants on humanitarian grounds and authorities will not push them out to sea if they do not plan to travel to a third country. If Rohingya are spotted in Thai waters, the navy will extend assistance in line with international practices. As far as providing shelter, and the possibility of immigration detention, Thailand has not commented. Given Thailand’s history of immigration detention policy, it is likely that such an approach will apply to Rohingya.

In both Malaysia and Thailand, many Rohingya are currently held in immigration detention facilities that fall far below minimum international standards, and in the case of Thailand in particular, Rohingya can be subject to indefinite detention.

Immigration detention should always be a last resort. No one should be subject to indefinite detention. Governments should implement alternatives to detention that ensure the protection of the rights, dignity and wellbeing of individuals. These basic minimum human rights standards are often breached, when there aren’t defined limits on the length of detention.

There are alternatives to detention that better respect the human rights of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants. Further, alternatives cost 80% less than immigration detention. In the case of people who are stateless, detention should never be used.

India: Already home to thousands of Rohingya, and unlikely to accept more

While in the past India had welcomed Rohingya refugees, a rise in nationalist and anti-Islamic sentiments have prompted demands for their deportation.

Due to discourse undertaken by Suu Kyi, there is an idea surrounding fleeing Rohingya as comprising mostly of Islamic terrorists. India worries that these refugees pose a security risk to India, and may further radicalize the existing political environment, In effect, around 40,000 undocumented migrants may be deported if India decides to do so. Ultimately, India are not accommodative of fleeing Rohingya and unless it is pressured by the international community, it probably won’t be swayed.

This article was authored by Jorge Nicholas as part of Asia Pacific Communications Internship.

Malaysia Immigration Raids

Aegile Fernandez, the Director of Tenaganita

Over 6000 individuals have been arrested and detained this month, as part of a series of mass raids conducted by immigration officers across Malaysia.

The raids began on 1 July, the day after the expiration of the deadline for all undocumented foreign workers to register for a Foreign Worker Temporary Enforcement Card (E-Card). The program was intended to provide all employers who have hired foreign workers without work permits an opportunity to register their employees, with the aim of addressing labour shortages in certain economic sectors.

IDC Members, such as Kuala Lumpur-based migrant rights group Tenaganita, have expressed concerns that this tough approach has forced immigrants into hiding and increased the risk of human trafficking.

"It's unjust to arrest and handcuff them, then put them in detention centers and deport them. They have paid money to employers and agents to get permits but it is not done" said Aegile Fernandez, the Director of Tenaganita.

Businesses in Malaysia have also spoken out about the raids, claiming that the process to obtain permits was unclear and rife with corruption, and that the workforce is likely to experience price hikes in the near future in the resulting labor shortage.

A policy of detention as the first resort in Malaysia has resulted in overcrowding in the detention depots and difficulty in managing detainees, in turn resulting in excessive strain on officers in the Immigration Department, especially those working in depots. The ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) has also expressed concerns over the risk of worsening conditions as a result of these raids.

“The Malaysian government must provide answers as to how they are addressing this sudden influx of thousands of detainees and how they will ensure that conditions do not deteriorate further,” said Mu Sochua, an APHR board member and member of the Cambodian National Assembly.