Alternative Care Models for Migrant Children Protection Protocol

On Mexico's southern border, IDC supports alternative care models and strategies for strengthening local implementation of Mexico's Migrant Children Protection Protocol

IDC Americas brought 2019 to a close with the third regional Forum for exchange and strengthening among local and federal authorities, as well as civil society organizations and international organisms working in support of migrant children. On this occasion the Forum was hosted in Chiapas, a state on Mexico’s southern border. The objective was to identify the obstacles and opportunities presented by the implementation of Mexico's Migrant Children Protection Protocol, at all times preventing migrant detention in this population.

A video was screened at the beginning of the event, featuring the opinions and reflections of various young migrants currently living at a secondary reception facility. In this video, they talked about their experiences, for the most part traumatic, of having been locked up inside a detention centre for various lengths of time. This exercise served as a guide for the sessions and so that participants bore in mind the reasons why being deprived of liberty on migration grounds is incompatible with a child’s best interests.

In the first panel on best practices, Mexico’s Child Protection Authority [Procuraduría Federal de Protección] shared the work carried out in Tapachula, a city on the border with Guatemala, as a result of the mass movements of people entering through this city last year, featuring significant numbers of child migrants. For its part, the Comitán regional protection authority highlighted a success story in which a group of children were taken out of a migrant holding centre and placed in a secondary reception center. Finally, SOS Children’s Villages [Aldeas Infantiles] spoke about how the organization had to adapt their care model to new necessities, which in this case include operating as a support centre for migrant children in primary and secondary reception facilities.

The Executive Secretary for Mexicos’ National Child Protection System [Sistema Nacional de Protección Integral de Niñas, Niños y Adolesentes, or SIPINNA] went over the process for creating the System’s Commission for Child Protection [Comisión de Protección de niñas, niños y adolescentes] and the adoption within the aforementioned Commission of the Migrant Children Protection Protocol as part of efforts to prevent children from remaining in detention.

Finally, the American organization KIND presented a system for the protection of children in the United States such that the authorities and civil society are aware of the options available to those children with family in the country.

The second working day was dedicated to discussions in working sessions which dealt with the various phases of the protection protocol, such as identification and evaluation, determination of best interests, restoration of rights, implementation of initiatives and the monitoring of “plans for life”. The working sessions showed consensus on topics such as a lack of both resources for protection authorities and available space for receiving migrant children. Specialized attention for different types of migrants was posed as a challenge, as well as the need to generate synergies with those individuals or entities that give support in each phase of the protocol.

Noteworthy among best practices are the efforts made by the protection authorities to work jointly with civil society in legal representation and in implementing plans for the restoration of rights, as well as in coordinating among authorities. This area highlighted the efforts made to obtain statistics for child migrant protection and to place them in primary and secondary reception centres.

Without doubt, these spaces serve to create support networks among those responsible for protection, in order to understand the processes and opportunities for advocacy, as well as to adopt certain commitments resulting in the local-level implementation of the protection protocol in support of liberating children from migrant holding centres within the framework of an alternative care strategy.

Interview With Our New Africa Programme Officer

In September 2019, we welcomed Florence Situmbeko to the African team, she is based in Windhoek, Namibia. Florence, will bring her long experience as a frontline Social Worker for government, as well as anti-trafficking and project management expertise to support the IDC’s work. We asked her some questions:

The IDC has found that the most successful “alternatives to immigration detention” use individualised case management across all stages of the migration process, to ensure a coordinated approach to each case. Florence - what is your case management/social work experience and what do you see as the value of case work for individuals?

All social workers are trained to be case managers - whether you’re working with individuals, families or groups. My role as a social worker has typically involved listening to my client’s story - why they came to see me or why they were referred to me, following a case through from the beginning until the end. One recent case was a boy whose mother was a Namibian national living in Namibia his father was a citizen of another country. When the father passed away, the boy moved to Namibia to live with his mother. When the boy came to see me, we figured out together what their immediate needs and priorities were. From assessing if he needed a place to stay, something to eat, to see a doctor? We realised he only needed help with acquiring documents so he could reside regularly in Namibia with his mother. I accompanied him to the Ministry of Home Affairs, explained his case, and followed up with the case until he received the documents. I also made sure he was administered an interim receipt that would ensure he was immune to arrest or questioning by the police while his case was being resolved.

beginning until the end. One recent case was a boy whose mother was a Namibian national living in Namibia his father was a citizen of another country. When the father passed away, the boy moved to Namibia to live with his mother. When the boy came to see me, we figured out together what their immediate needs and priorities were. From assessing if he needed a place to stay, something to eat, to see a doctor? We realised he only needed help with acquiring documents so he could reside regularly in Namibia with his mother. I accompanied him to the Ministry of Home Affairs, explained his case, and followed up with the case until he received the documents. I also made sure he was administered an interim receipt that would ensure he was immune to arrest or questioning by the police while his case was being resolved.

Here, you can see that case management can range from more intensive for complex cases, and less-intensive such as administrative support for more self-sufficient migrants who already have their basic needs attended to, like the young boy.

We keep comprehensive, confidential case files on everyone who we assist. Protecting our client’s privacy is paramount, and this also links to our credibility as an Agency. We are able to discuss cases during our monthly reports in which we anonymise cases and share our challenges and shed light on systemic issues and recurring problematic or productive trends.

You mention systemic issues - as a case-worker, have you been involved in policy or advocacy work based on evidence gained through social work practice? In turn, how can evidence-based practice be used to create systemic change?

Yes, as a caseworker, it is worth being engaged with stakeholders who are drafting policies and maintaining good relationships with them - as, afterall, their work directly informs what happens on the ground. Social workers have a unique vantage point as they can feed information from the ground level upwards, illuminating gaps, what is working or what is not to better influence systemic change. If not, such policies are not based on context specific evidence, and we end up assuming.

Social workers have a unique vantage point as they can feed information from the ground level upwards

As a social worker with the Ministry of Gender, the Ministry of Health in Namibia, and then working with IOM, I provided input into legislations or policies. For example, with IOM, I gave inputs on what needs to be taken into consideration when dealing with victims of trafficking, including children, for the development of the Combating of Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Act, no. 1 of 2018 - to ensure the rights of people who might be more vulnerable than others. I was also part of a team that contributed towards the formulation of the Regulations on Human Trafficking and the National Action Plan on Gender Based Violence in Namibia.

How have you worked with other stakeholders as a social worker to bring change and or support the people/”clients” you were working with?

Beyond the policy arena, we work with many other stakeholders to develop support systems for the people we work with. There is no way one institution can fully assist a person as the person has different needs. Therefore, networking is an important part of the social worker’s day to day tasks.

It is worth getting to know the services and organisations around you so you know exactly who to reach out to: “the Red Cross can help me with that”, “my contact at the Home Affairs head office will be able to help me with this”. As well as proving beneficial to the “client”, networking is also useful when it comes to advocating for specific policies/legislation.

Case conferencing is one useful way to maintain your networks and delegate responsibilities to different stakeholders. One case involved several young women who had been trafficked, and who wanted to return to their home country in Zambia. We called a meeting with a shelter manager, IOM, the police, Home Affairs, the social workers from the Ministry of Gender and Office of the Prosecutor General. Through individualised assessment of their cases, we assigned different responsibilities. We were also in contact with social workers in Zambia to ensure that it is safe for the girls to return back home and also ensured that their families were being prepared to receive them. The girls were reintegrated into their communities, after a number of counsellings sessions in order to minimise their vulnerability, for example, one family, based on what they requested received livestock, basic training on how to take care of the livestock and also basic training on financial management. Since the girls were minors arrangements were made for them to return back to school.

Thank you Florence, we are looking forward to working with you.

Turning the Tide of Detention: What Role Can European Cities Play?

Written by Barbara Pilz and Jem Stevens

European cities are increasingly involved in debates around migration governance. What role could they play in building systems based on engagement with people, not enforcement and immigration detention?

Not just for national governments

Migration management is often thought of as the domain of national governments. But a group of European cities is highlighting their role in working with irregular migrants, producing guidance and bringing their voices to European-level policy making through the C-MISE exchange.

Something stands out about their work: these local level authorities focus on support and services for people without documents. A stark contrast to the enforcement, deterrence and detention approach increasingly popular among national governments in Europe.

Closer to the realities of irregular migration

Perhaps this isn’t surprising, as cities have competence in ensuring the welfare of residents and are closer to the realities of irregular migration. They witness first-hand the experiences of people without documents who often can’t access basic services and the challenges this brings for individuals, local communities and authorities.

In Athens, Eleni Takou of Human Rights 360 shares “Most people without documents end up in Central Athens, either under the radar or seeking onwards routes. This has meant Athens city has to be proactive – it has a coordination centre for NGOs and other stakeholders, and has been active in providing services and supporting referrals to housing and healthcare.”

Addressing local concerns: approaches that work better

Impoverishment, homelessness, destitution and barriers to social cohesion are some of the challenges cities face, linked with irregularity. People are often detained repeatedly and sometimes for prolonged periods, in violation of EU legislation. And when they are released from detention, with all the problems this brings, cities have to pick up the pieces.

So could collaboration among cities and NGOs provide another way, addressing local concerns while better ensuring rights and resolving cases in the community, without immigration detention?

Jan Braat of the City of Utrecht, who chairs the C-MISE exchange, thinks so: “In the Netherlands, 50% of people [in an irregular situation] end up on the streets – the national government’s approach hasn’t worked. We’ve shown that it’s better to build trust and work with people”.

Building trust, solving cases in Utrecht

Utrecht City partners with NGOs to provide professional guidance and support to people without documents, to reduce irregularity in the city. The programme has achieved case resolution for most its clients: since 2002, 59% of participants received legal status, 19% returned to their countries of origin, 13% re-entered national asylum shelters, and only 8% disengaged.

Rana van den Burg at SNDVU, an implementing NGO, tells us about their approach:

“The key to our support is that it’s based on trust between the contact person and the client. People often believe that their case hasn’t been looked at properly by immigration authorities, increasing distrust in the system and facilitating disengagement from the procedures”.

At SNDVU, a contact person accompanies each individual throughout the migration procedure and ensures they have access to clear and accessible information in order to make difficult decisions. Along with this professional guidance, the programme provides accommodation, pocket money, legal aid and social support so that people can meet their basic needs and actively participate.

Rana explains that “working together with people and having a judgement free attitude, while facilitating their agency and decision-making is the key to resolving cases”. The programme does not impose a time limit for participation, in order to give participants time to explore all options for case resolution. An agreement with the police means clients can’t be detained.

Growing evidence

While this approach is still innovative in Europe, there’s growing evidence that it works. Last year, an in-depth Council of Europe analysis found that trust and support, including individualised case management, are key to effective alternatives to immigration detention (ATD). Evidence from three NGO-run case management pilot projects in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Poland, backs this up.

NGOs are often well placed to implement case management ATD programmes, with expertise in working with one to one migrants and building the rapport necessary foster engagement. And as civil society organisations consider how pilot projects can be scaled up towards systems change, cities stand out as potentially important stakeholders.

Influential stakeholders

Not only do cities have the ability to mobilise services and support networks available in their community, as first responders, they can act as entry points to regional and national governments. Their voices could be influential in changing narratives around migration and detention.

From this year, for example, Utrecht’s professional guidance programme is receiving funding from the Dutch national government. This is part of an agreement with five municipalities which will provide 59 million EUR funding for pilots over three years (in Utrecht, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Eindhoven and Groningen) - and has enabled Utrecht to expand its programme.

It’s significant that with this agreement, the Dutch national government has shifted away from an exclusive focus on returns which it doggedly maintained for years. Could this multi-level collaboration provide a step towards systemic change? For local NGOs, maintaining independent quality case management - which genuinely supports people to explore all options (rather than focusing on return) and make decisions in an informed and dignified way – will be key.

Meanwhile, the European Commission is engaging cities on irregular migration, rightly recognising that national governments can’t do this alone. The C-MISE cities have a refreshing message in this debate: they want to start a conversation acknowledging that EU policies should not disregard the social hardships lived by irregularly staying migrants and that more inclusive responses are needed.

Multi-level collaboration as a route to change

EU policy and national governments are increasingly relying on enforcement and detention to try to achieve migration management goals. But it’s well known that detention is not only harmful and costly, it does not promote case resolution.

In this challenging context, collaboration between cities and NGOs could develop approaches that treat people as human beings, supporting individuals to resolve cases in the community without detention.

For cities, this could provide a way to address local challenges, while informing and influencing national and European policy. For civil society, it could provide the building blocks for systems based on humanity and dignity that work better for everyone.

Shifting the narrative and practice on migration management - from enforcement to engagement - is a multi-level task that requires collective action.

IMPORTANT: Call for Inputs on Immigration Detention

WHAT: The Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families has decided to elaborate General Comment No. 5 on Migrants’ Rights to Liberty and Freedom from Arbitrary Detention. This is a critical opportunity to provide input and feedback on fundamental human rights issues. The Committee invites all stakeholders to provide inputs to this initiative through a questionnaire by 1 April 2019. The concept note and questionnaire are available in English and Spanish HERE.

HOW: Please send responses electronically in Word format to [email protected] with subject line “Submission for General Comment on Migrants’ Right to Liberty.” Submissions should not exceed 10 pages. Written submissions will not be translated and should preferably be submitted in English, however submissions in French and Spanish will also be accepted. All submissions will be posted on the webpage of the Committee unless explicitly indicated to the contrary.

Any questions should be addressed to the Secretary of the Committee, Mr. Luc Mubiala, at [email protected].

If you would like to inquire about being connected to other organisations in your region also working on responses, please contact the following IDC regional offices:

Americas [email protected]

Europe [email protected]

Africa [email protected]

Middle East & North Africa [email protected]

Asia Pacific [email protected]

Celebrating 29 Years of the CRC

On Tuesday November 20th, the Initiative for Child Rights in the Global Compacts held an event at the Palais des Nations, “Child Rights and the Global Compacts: A Call For Action,” to commemorate 29 years of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Keynote Speakers were:

- H.E. Ambassador Socorro Flores Liera of the Permanent Mission of Mexico

- H.E. Ambassador Eunice Kigenyi of the Permanent Mission of Uganda

- Video Message from several Syrian and Afghani girls experiencing forced migration

A panel of experts discussed and defined concrete actions and initiatives, with a multi-stakeholder approach, that will contribute to putting children’s rights at the heart of the implementation of the Global Compacts. Panelists included:

- Philip Jaffe, Member of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child

- Ellen Hansen, Senior Policy Advisor to the Assistant High Commissioner for Protection

- Michele Klein Solomon, Director, Global Compact for Migration, IOM

- Peggy Hicks, Director of Thematic Engagement, Special Procedures & Treaty Bodies Division

- Laurent Chapuis, Regional Advisor, Migration, UNICEF

- Constanza Martinez, UN Representative, World Vision

- Moderated by - Delphine Moralis, Secretary-General, Terre Des Hommes

The Global Compact on Refugees and the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration were adopted the very next day.

JRS Report on the Detention of Trafficked Men

IDC partner, JRS UK, has released a report based on the experience of 13 trafficked men. The report finds that a fundamental conflict between supporting trafficking victims and immigration control meant that victims continued to be detained. The UK government often ruled people in detention were not victims despite strong evidence to the contrary, and even those acknowledged to be likely victims were sometimes still detained due to immigration factors. Convictions and instances of non-reporting that were a direct result of being trafficked and held in modern slavery were routinely used to justify continued detention.

Download Below

TOPICAL BRIEFING: Survivors of Trafficking in Immigration Detention, October 2018

In Appreciation of Barbara Harrell-Bond

The IDC expresses deep gratitude for the work of Barbara Harrell-Bond, who died at age 85 in July.

Barbara was an active member of the IDC since it began in 2008. She consistently shared resources and her deep knowledge about immigration detention and alternatives to detention.

Barbara's legacy will continue to improve the lives of refugees worldwide. She is remembered for founding the Refugees Studies Center (RSC) at the University of Oxford and founding the African and Middle East Refugee Assistance (AMERA Egypt), an organisation dedicated to providing quality legal services to refugees and asylum seekers. She established the Refugee Law Project at Makerere University in Uganda, the Forced Migration and Refugee Studies Program at the American University in Cairo, and Africa Middle East Refugee Assistance (now AMERA International) to provide legal aid to refugees and ensure young people were able to study refugee law. She was a founding member of the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network.

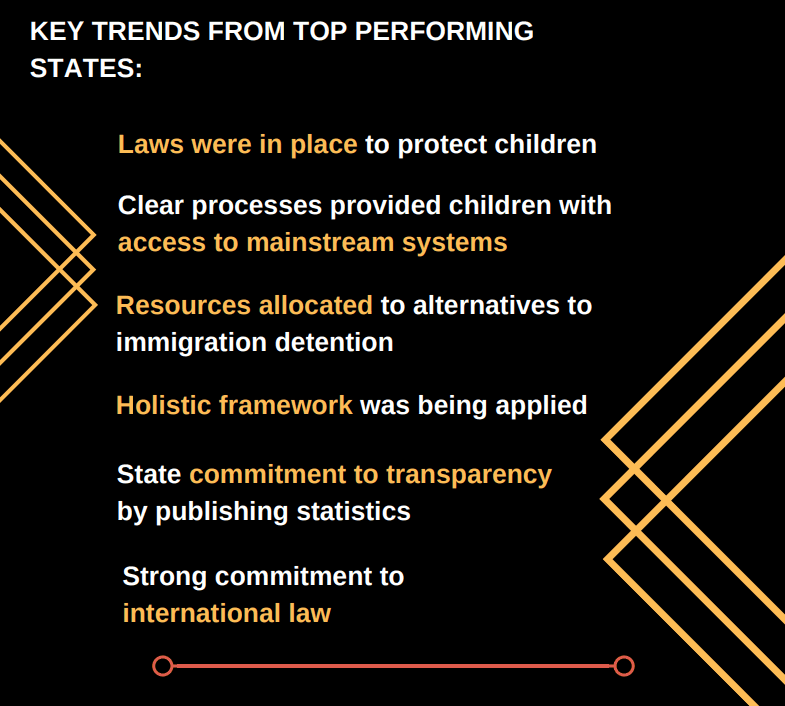

Cross-Regional Exchange on Ending Child Detention

The Permanent Mission of Brazil, the Permanent Mission of the Republic of the Philippines and the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Zambia, in collaboration with the International Detention Coalition (IDC), UNICEF and the Initiative on Child Rights in the Global Compacts, held a cross – regional exchange alongside the 5th negotiation of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

Thirteen States attended the event, sharing insights into migration governance that does not resort to child immigration detention. Many States are taking positive steps towards ending child detention, often with the support of international and civil society organisations.

In order to end the practice of child immigration detention globally, these positive practices and successful pilots should be shared, scaled up and promoted.

The exchange provided a space for States to share their experiences implementing alternatives to the immigration detention of children and explored how dialogue and experience-sharing could illuminate the implementation phase of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

The IDC has compiled some positive practices in the Briefing Paper Never in a Child’s Best Interests and developed a Roadmap for States working to End Immigration Detention of Children.

Search for examples of alternatives to detention in the IDC database.

Cross-Regional Exchange to Explore Ending Child Detention

The Permanent Mission of Brazil, the Permanent Mission of the Republic of the Philippines and the Permanent Mission of the Republic of Zambia, in collaboration with the International Detention Coalition (IDC), UNICEF and the Initiative on Child Rights in the Global Compacts, are holding a cross – regional exchange alongside the 5th negotiation of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.

The exchange aims is to demonstrate migration governance without resorting to child detention is not only possible, but it is in fact a reality in many States. Many States are taking positive steps towards ending child detention, often with the support of international and civil society organisations.

In order to end the practice of child immigration detention globally, these positive practices and successful pilots should be shared, scaled up and promoted.

The exchange will open a space for States to discuss their experiences implementing alternatives to the immigration detention of children and to explore how dialogue and experience-sharing could illuminate the implementation phase of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration.