10 Years of IDC’s Work to End Child Immigration Detention

Over ten years ago in 2012, International Detention Coalition (IDC) launched the Global Campaign to End Child Immigration Detention (the Global Campaign) at the 19th Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, Switzerland, supported by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Later that year, the Committee on the Convention of the Rights of the Child issued key recommendations on the rights of children on the move, and highlighted IDC’s proposed model for a move to community-based alternatives for children.

With the simultaneous release of Captured Childhood, a report based on 70 interviews of children with lived experience of immigration detention across 11 countries, IDC set in motion a global movement grounded in the vision of a world that cherishes the humanity and dignity of children. Specifically, IDC campaigned to persuade the international community and governments that the immigration detention of children and their families is always a child rights violation and is never in the best interests of the child. IDC offered evidence of positive actions that States could take instead of depriving children of their freedom, and put forward practical and current evidence of a new perspective of rights-based alternatives where children and their families could live in non-custodial community-based settings while their immigration cases were being resolved.

The Global Campaign joined opinions across diverse sectors in different parts of the world advocating for an end to immigration detention of children and families, with the message that immigration detention is never an appropriate place for a child and is never in the best interest of the child. The Global Campaign amplified the voices of children in detention through The Invisible Picture Show and showed the negative impact of even short periods of immigration detention on their mental health and development. The campaign called on States to step up to their international obligations, and ensure that all refugee and migrant children:

- Be treated first and foremost as children

- Be free

- Be looked after according to their best interests

- Live in freedom in the community with their parents or primary care-givers

As the Global Campaign expanded, it became a platform for national campaigns and advocacy strategies calling for an end to the immigration of children around the world, most notably in Australia, Greece, Malaysia, Mexico, South Africa and Tanzania, as seen in the Global Campaign’s history.

The Campaign also brought to light the issues of regional protection of children, for example family separation with detention and deportation procedures in the United States and the mass deportations of children and families to the Central American countries of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

IDC mobilised for States to adopt child-friendly, rights-based, humane, non-custodial and community-based alternatives to detention (ATD), as seen in this advocacy video developed in 2015 by IDC and partners A Tale of Two Children.

Following this, IDC also launched the NextGen Index in 2018, which served as a comparative tool to rank States on their progress in ending child immigration detention. The Index used a standard scoring framework to assess strengths, weaknesses, and key factors to ensure national migration management systems are sensitive to the needs of children and, importantly, avoid child detention.

The Inter-Agency Working Group (IAWG) to End Child Immigration Detention, an international alliance of civil society organisations and UN entities was key to convening global advocacy efforts from 2012 until 2018, with a critical turning point in the obligation of States being the adoption of the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants by the UN General Assembly in 2016. The subsequent negotiation process of the Global Compact for Migration and its adoption in 2018 represented a significant win by collective global advocacy efforts, in that it includes a clear commitment by States to work to end child detention by focusing on ensuring availability and accessibility of alternatives in non-custodial contexts.

The 2019 release of the UN Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty, to which IDC and its Global Campaign were key contributors, further added to the growing body of expert evidence on the harms of immigration detention on children and families, the extent of the practice and the solution-oriented approach based on alternatives.

Since 2018, the implementation of the Global Compact for Migration has provided a platform to concretely discuss and share national practice, legal and policy frameworks in global spaces. IDC pioneered efforts in this direction by leading regional and global discussions to develop a cross-regional peer learning platform on ending child immigration detention. This initiative led to the inclusion of peer learning as part of the UN Network on Migration Work Plan and the creation of the UN Network on Migration Working Group on Alternatives to Detention in 2019.

Since 2019, IDC co-leads the UN Network on Migration Working Group on Alternatives to Detention (ATD) alongside UNICEF and UNHCR, which prioritised supporting States in their work to end child immigration detention through global and cross-regional peer learning exchanges, organised in collaboration with the governments of Thailand, Colombia, Nigeria, Ghana, and Portugal. Recently the Working Group produced a global snapshot on Ending Child Immigration Detention, which highlights efforts in Mexico and Zambia, as well as an accompanying video. The Working Group is planning, together with key champion States, another peer learning exchange on ending child immigration detention in 2023.

We saw further international progress into 2021 with General Comment 5 to the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, which called for child immigration detention to be fully eradicated globally. Child immigration detention was also a centrepiece of detention-related discussions at 2022's International Migration Review Forum (IMRF), with some States making pledges to end the practice entirely.

Where Change Happens

While the influence of global standards and political frameworks is a critical point of intervention for IDC, the core of our work exists at local and national levels, which is where change and impact is directly felt by communities at risk of immigration detention.

Following over a decade of coordinating multi-level advocacy, collaboration between civil society organisations, international partners, federal and local government authorities, and communities in Mexico, IDC was proud to be part of an historic political moment in 2020 when the Mexican Congress declared that immigration detention is no place for children.

This 2020 legislative reform that now legally prohibits the detention of children for immigration reasons came on the heels of a pioneering collaboration in joint advocacy by migrant and child rights groups in Mexico. This collaborative IDC work involved key partnerships with UNICEF and UNHCR, the Global Campaign, hearings before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, as well as clear recommendations to Mexico from the IACHR and the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child.

New legislation in 2014 established a national protection system for all children, along with regulations that specifically prohibited their confinement in immigration detention centres. This opened up opportunities for deeper IDC engagement with immigration authorities, providing technical advice for the development and implementation of the successful first ATD pilot for unaccompanied children. The pilot was developed and implemented in collaboration with SOS Children's Villages (Aldeas Infantiles) and Covenant House (Casa Alianza), two organisations with strong community models and long-term experience working with children in Mexico. ATD initiatives demonstrated how children and families can be supported to live in the community as they participate in their ongoing migration or asylum process.

In the challenge to contribute towards effective implementation of the legal prohibition on child detention, IDC continues to prioritise engagement with the National Commission for the Protection of Migrant Children through capacity building and technical advice at federal, state and local levels. As a result of these efforts, we have seen the adoption of a National Protocol for the Protection of Migrant Children and we are currently working with state committees to develop and adopt local protocols that will serve to improve protection gaps and coordination among authorities at borders and along migration routes.

IDC believes it is important to continue to work on the ground, as close as possible to children and families with lived experience, local authorities and local civil society organisations, especially public and private shelters to strengthen community-based reception and care models. We also continue engagement with the Mexican legislature including training and harmonisation of the legal framework.

IDC Americas Regional Coordinator Gisele Bonnici states of these long-term efforts:

“Working side by side with our dedicated partners in Mexico, IDC continues to promote and support practical implementation of effective and appropriate community-based reception and care options for migrant and refugee children. Our goal is that no child, whether travelling accompanied or unaccompanied, be detained for any period of time in any type of space for immigration reasons.”

Similarly, in 2019, representatives of 7 Thai Government agencies signed the Memorandum of Understanding on the Determination of Measures and Approaches Alternatives to Detention of Children in Immigration Detention Centres (ATD-MOU), as well as Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) to implement the MOU-ATD starting in September 2020. The MOU-ATD was a concrete outcome of a pledge made by Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha during the 2016 Leaders’ Summit on Refugees at the United Nations in New York. At the summit, he publicly pledged to end the immigration detention of refugee and asylum seeking children in Thailand.

Following this huge political commitment, IDC has worked with local partners, such as HOST International to collate and strengthen the evidence-base that can be used to increase practical understanding of community-based, rights-based, and gender-responsive ATD to better protect children and their families in the context of migration; including, a Global Promising Practices on ATD which contextualised our design to the Thai context, a Community-based Case Management Programme Evaluation, as well as an accompanying Practices Guidelines on Community-based ATD in Thailand. Along with the Thai government Department of Children and Youth – Ministry of Social Development and Human Security (DCY) and UNICEF Thailand, IDC developed a government Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning (MEL) framework in line with key international standards to track progress on the MOU-ATD implementation. The evaluation led by DCY aims to take place in 2023 as a collaborative effort of key stakeholders in Thailand.

For several years now, IDC has seen our members and partners engaged in advocacy and service provision for children impacted by immigration detention. With IDC’s support, members in Thailand and Malaysia define strategies to end child immigration detention in their countries. These strategies have prioritised and coordinated efforts towards the ultimate goal of ending the immigration detention of children and their families.

IDC Southeast Asia Programme Manager Mic Chawaratt states of IDC’s efforts in Thailand:

“Political will, commitment to the best interest of the child, and multi-stakeholder collaboration have been the key drivers of advocacy efforts among Thai civil society, government partners, UN agencies, the diplomat community, academics, and people whose lives are impacted by immigration detention. I believe that one day immigration detention will no longer exist in my country, and people who migrate here will live with rights and dignity – which is IDC’s vision for the world.”

Additionally in the Asia Pacific region, the Ministry of Home Affairs in Malaysia officially launched an ATD pilot programme in February 2022 for unaccompanied and separated children following approval of the pilot by the Malaysian cabinet in 2021. This was a key milestone for IDC following a decade of ongoing advocacy that centred around an incremental and collaborative strategy alongside our members, the human rights commission (SUHAKAM) and UN agencies. The national campaign in Malaysia was originally spurred by the Global Campaign, and provided leverage and a space to engage a broad number of groups around the issue, while previously the discussion on this issue was severely limited. Now, the planning, development and implementation of the pilot is being supported by IDC partners SUKA Society and Yayasan Chow Kit.

Following this development, IDC continues to coordinate the End Child Detention Network Malaysia (ECDN), and brings members together to discuss strategy and collective advocacy efforts. IDC has also started a public engagement programme in Malaysia, including new initiatives focused on developing public and media engagement strategies on refugee and migrant rights.

In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) this year, and in partnership with UNICEF, IDC organised a series of online ATD trainings focused on screening, assessment, referral mechanisms of children, as well as case management and community placement options for children. IDC believes that these critical elements serve as a framework for identifying and developing rights-based ATD. This training series aims to strengthen the capacity of civil society organisations, as well as bring together a network of actors working in the field of ending child immigration detention across the region. The latest training in October 2022 was attended by 50 participants working on issues related to refugee and migrant children from more than 10 countries in the MENA region.

IDC has also carried out a mapping research with UNICEF on the current legislations, policies and practices with regards to child immigration detention in the MENA region. This led to the production of two policy briefs targeting governments; which aim to support sharing among governments in the MENA region, and to strengthen practices in line with the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Global Compact for Migration (GCM). The mapping analysed trends and identified promising protection and care practices for refugee and migrant children with a focus on child-sensitive alternatives to custody across 9 countries in the MENA region: Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan.

In November 2022, IDC co-organised with UNICEF a regional workshop for 8 governments in the MENA region, to present and share promising protection and care arrangement practices for children on the move, from across the region and beyond, facilitating discussions and exchanges on common challenges, strengths, and proposed ways forward for their countries and across borders. The workshop highlighted key aspects from the child protection continuum from identification and referral to alternative care models specifically highlighting promising practices on child protection including child sensitive alternatives to custody.

In Europe, meanwhile, efforts have been ongoing to advocate for an end to child detention. The conditions set out in EU law, alongside the requirements of the European Convention on Human Rights and the case law of the European Court of Human Rights, make it clear that depriving children of their liberty is only permissible in exceptional circumstances. Despite this, however, at least 27 countries in the region still detain children. IDC has been working with civil society organisations across Europe to train policymakers, child protection experts, judges and lawyers on the legal requirements of states when it comes to ensuring alternative care arrangements for children. This has included working with the International Commission of Jurists to support the roll-out of a set of training materials on ATD for migrant children. In addition, the Belgian member of the European ATD Network - which IDC coordinates - has been implementing an ATD for families with children since 2020, working to ensure that children can live in the community while they and their parents work to resolve their migration status.

As with any major policy chance, progress often feels slow and can even appear to be moving backwards at times. The provisions for reception and border procedures set out in the new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum, for instance, are likely to result in a dramatic deterioration of the rights of people on the move, including children. Yet there remain signs of hope; Germany's pledge at the 2022 IMRF to end immigration detention of children, and indications from a number of governments that they are working to integrate children on the move into mainstream protection systems, show that there is still space to move forward with this agenda.

Lived Experience at the Centre

In 2012, the UN Committee on the Rights of Child declared that immigration detention is a violation of a child’s rights. This declaration represented a clarity of language that began a shift in international law, and the shift was made following a performance by five young advocates who IDC partnered with to share their experiences of detention, as well as their proposed solutions, at the UN. They curated a theatre piece called Hear Our Voices, and powerfully stood before global policy makers and academic experts to stake their claim on this issue. Together, they moved the dial on child immigration detention worldwide.

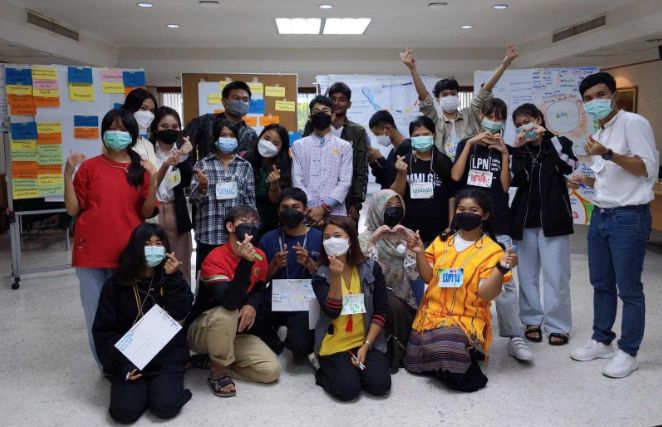

IDC continues to believe that people with lived experience of detention need to be involved in shaping the policies that directly impact their own lives and communities. IDC recently co-organised the Children and Youth Affected by Migration-Led Advocacy Workshop, which involved conducting youth engagement training for 43 different local partners, as well as leadership and advocacy training for 175 migrant and refugee children and youth in Thailand. The youth leaders were then invited to share a statement directly with policy-makers in April 2022 at a forum attended by Thailand’s Representative to ASEAN Commission on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children (ACWC), representatives from the Thai government, as well as international organisations and NGOs.

Further in Malaysia, IDC works with Akar Umbi, a local NGO, to conduct a leadership programme called the Azalea Initiative with a group of young refugee women in Kuala Lumpur. The programme’s goal is to support their empowerment, and build their capacities as changemakers within their communities.

In Mexico, IDC and its partner SOS Children’s Villages in Comitán, Chiapas have engaged young people from migrant communities in leadership training and activities, piloting methodology adapted from IDC’s Community Leadership Curriculum. IDC also worked with partners to support migrant children to create video documentaries of their own experiences and hopes for the future.

Grounded, community-based efforts like this, alongside coordinated advocacy strategies to amplify impact, have been the heart of IDC’s work to end child immigration detention worldwide. While we have taken the lead on global events and international outcomes on child detention, we have also worked side by side with regional partners and national coalitions to develop tailored and transformative strategies that make a real impact on the ground. This year, IDC re-commits to our ten year, long-term effort to end the immigration detention of children all over the world, in line with our broad vision of ending immigration detention for all.

Written by Gisele Bonnici, IDC Americas Regional Coordinator and Mia-lia Boua Kiernan, IDC Communications and Engagement Coordinator

Director's Report: IDC's New Mapping Research

Written by Carolina Gottardo IDC Executive Director

In September 2022, IDC was proud to officially launch two pieces of research and their accompanying country profiles: Our global mapping report Gaining Ground: Promising Practices to Reduce and End Immigration Detention, and our Asia Pacific report Immigration Detention and Alternatives to Detention in the Asia Pacific Region, which was developed in collaboration with the Regional UN Network on Migration for Asia and the Pacific under the umbrella of the UN Network on Migration.

Our launch event in September featured a Cross-Regional Roundtable Dialogue that brought together representatives from communities, organisations, and governments across the world to discuss promising practices that illustrate the potential for migration governance without immigration detention. We heard from these experts at local, national, regional, and global levels about how to use this new research to scale up rights-based alternatives to detention (ATD) and further advocacy to reduce and ultimately end immigration detention, including by supporting improved implementation of the Global Compact for Migration (GCM).

For almost 15 years now, IDC has worked alongside its members across the globe to strategically build movements and influence law, policy and practices to end immigration detention and implement rights-based ATD. IDC prioritises research and building an evidence-base to support in this effort, and since our founding, we have published over 35 international, regional and national research reports and briefing papers related to immigration detention and ATD.

As set out in our flagship report, There Are Alternatives, ATD shifts the emphasis of migration management away from security and restrictions towards a pragmatic, proactive and solutions-based approach focused on case management, case resolution and human rights. As detailed in IDC’s 2022 position paper, Using ATD as a Systems Change Strategy Towards Ending Immigration Detention, IDC believes in alternative approaches that respect refugees, migrants, people seeking asylum and others on the move as people with rights and agency, who can be supported through immigration processes while living in the community, without being deprived of their liberty.

New Research

IDC’s new research shows that progress in moving away from the use of detention has been slow, and too often there continues to be a lack of awareness among governments, local authorities and other actors of alternative approaches. However, in recent years IDC has seen a number of states begin to recognise that effective and feasible alternatives to detention do exist. This has led to shifts that include the adoption of laws and policies enshrining non-detention or setting out ATD, the introduction and scaling of community-based pilot projects, establishing screening, assessment and referral mechanisms that help to reduce the use of detention, as well as the development of alternative care arrangements for children which - in the best cases - integrate migrant children directly into national child protection systems.

IDC’s new research aims to set out some promising practices, and provides an overview of practical examples and recent developments in the field of ATD, in order to encourage further progress in this area and to inspire and embolden governments, local authorities, international organisations, community actors, civil society and other stakeholders, with steps they can take to move away from the use of immigration detention which is ultimately what we want to see.

Given the ample scope of the two reports, it is very difficult to provide a fitting summary. However, I would like to highlight a few key findings:

- The use of immigration detention continues to be widespread in most regions of the world, probably with the exception of South America. A number of countries continue to detain people arbitrarily and, in some cases, without putting a time limit on the amount of time people can be detained. The Asia-Pacific mapping report, in particular, has highlighted the lack of regular and comprehensive screening for individual vulnerabilities, and limited recourse to challenge detention decisions before a court or independent administrative body. However, this is by no means unique to this region, and across the world we have found that the structures and processes necessary to ensure that people are not detained are missing or inadequate.

- The sheer diversity of people at risk of immigration detention across the world continues to be staggering. This includes migrant workers, refugees, people seeking asylum, stateless persons, undocumented migrants and survivors of trafficking, amongst others. It is critical to view the impacts of immigration detention through an intersectional lens, and to understand that people’s diverse and intersecting identities impact them in very specific ways. This includes migrant women, girls, transgender, gender diverse, and LGBTI+ communities, who are all likely to have very specific experiences of immigration detention that will coincide with the layered harms of also facing discrimination based on race, ethnicity, religion, disabilities and culture, among other factors.

- Despite the challenges and gaps that persist across most regions of the world, there have nonetheless been a number of encouraging developments. These include the introduction of laws, policies and practice that prohibit immigration detention in law, either across the board or of certain groups, or that introduce ATD in law, or result in people being released from detention. There have been efforts in some countries towards regularisation and the provision of legal status and documentation, and in others, efforts to implement better screening, referral and assessment mechanisms. There is also an increased willingness on the part of some governments to work towards a whole-of-government and a whole-of-society approach to migration, often utilising peer learning initiatives at the regional and global levels. There has also been important progress and momentum built towards ending the immigration detention of children, with several countries either not detaining children in practice or introducing legislation to restrict the detention of children and other efforts to strengthen child protection systems and alternative care arrangements.

The examples highlighted throughout the reports range from rights-based ATD initiatives and programmes to other developments in law, policy and practice that - while perhaps not always ATD per se - represent promising steps towards reducing and ending immigration detention. What all the examples have in common is that they contain some of the elements that IDC sees as necessary for states to move away from detention as a tool of migration governance.

While these reports only represent a snapshot of what is currently going on around the world, we at IDC hope that by showcasing such examples we will contribute to the sharing of ideas, experiences, challenges and progress in this critical area of migration policy and that governments and other actors are encouraged to take steps to implement ATD and end immigration detention.

Finally, when thinking about grounding and impact and building momentum towards reducing and ending immigration detention, we need to think first and foremost about the people affected by these policies who should be at the forefront of these efforts. This brings to my mind a quote from a person affected by immigration detention who said, “to end detention we will need the same perseverance and determination as those who have survived detention.” We must stand firmly in this struggle with perseverance and determination.

Working to Uphold People’s Rights in the Digital Age of Migration Policy

IDC’s New Workstream on Technologies, Detention & Alternatives to Detention (ATD)

Whether we like it or not, when it comes to migration governance digital technologies are here to stay. From customer service portals to collection of biometric data, forecasting models to face recognition tools, over the past two decades such technologies have been increasingly used by governments across the world in the conception and design of their migration systems. The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this trend.

Yet, these types of technology are never neutral. There is no such thing as a technical ‘fix’ to a complex problem, and efforts by some to portray digital technology as the solution to human bias have been shown to be at best naïve, at worst dangerous. When Artificial Intelligence (AI) and digital technologies are employed, this is a political choice. But the people deciding rarely experience these policies themselves. It is people on the move, as well as their families and communities, who ultimately find themselves at the ‘sharp edges’, subject to policies and practices that they have no control over and little to no agency in shaping.

Technology & (Alternatives to) Immigration Detention

Immigration detention and alternatives to immigration detention (ATD) have been acutely impacted by the expanded use of technologies in migration governance systems. For instance, certain digital technologies utilised within the carceral system (e.g. ‘Smart Prisons’) are now being adopted in the context of immigration detention. Meanwhile, technologies such as electronic monitoring and facial and voice recognition are being used or explored by a growing number of governments, ostensibly as part of their efforts to move away from the widespread use of immigration detention and put in place ATD. While this may seem like progress, these trends raise serious concerns for IDC.

Information surrounding the use of tech in ATD – and its impacts on people – remains largely confined to data from a few key countries (namely Canada, the UK and the USA). But we know that an increasing number of governments are contemplating the idea of employing such tech, if not already actively using it. In the European Union, for instance, Denmark, Hungary, Luxembourg and Portugal have all established the use of electronic tagging in law or administrative regulations. Turkey, meanwhile, has included electronic monitoring on a list of authorised ATD included within amendments to the Law on Foreigners and International Protection made in 2019 (but yet to be implemented).

IDC members working with communities and individuals affected by detention or at risk of detention, have been increasingly expressing concerns about the growing use of such technologies in the immigration detention space. People at risk of immigration detention are particularly vulnerable to the misuses of digital tech; they often have precarious immigration status and thus little ability to assert their own rights if technology is abused.

Over the coming months IDC plans to launch a workstream focused specifically on the use of technology and AI in immigration detention and ATD. In particular, we aim to examine:

Alternative Forms of Detention & De Facto Detention

On the whole, research to date has focused on how States have used digital technologies to further restrict people’s liberties, undermine their human rights, and increase surveillance and enforcement. This has been labelled “techno-carcerality” in the context of the Canadian government’s ATD programme, and represents “the shift from traditional modes of confinement to less traditional ones, grounded in mobile, electronic, and digital technologies.” A report on the Intensive Supervision Appearance Programme (ISAP) in the USA stated that its electronic monitoring components amount to “digital detention.”

Over the years, IDC has warned against the use of alternative forms of detention – which are de facto deprivation of liberty, simply detention by another name – and the potential for the term ATD to be co-opted and used as a smokescreen for such initiatives. Specifically regarding electronic tagging, IDC has been clear:

IDC classifies electronic tagging as an alternative form of detention rather than an alternative to detention, as it substantially curtails (and sometimes completely denies) liberty and freedom of movement, leading to de facto detention. It is often used in the context of criminal law and has been shown to have considerable negative impacts on people’s mental and physical health, leading to discrimination and stigmatisation.

More broadly, electronic monitoring devices pose a threat to personal liberty as a result of heightened surveillance and indiscriminate data collection. We know, too, that voice and facial recognition technologies have questionable accuracy, especially for communities that are racialised. This can lead to mistakes that have serious and irreversible consequences – including detention, deportation, and the separation of families and loved ones.

Tech as a Way to Improve Engagement?

Yet there are also some anecdotal reports that the use of digital technologies in ATD can have some benefits for people on the move. One notable example is the shift in the UK from in-person reporting to telephone reporting. This approach was originally tested during the pandemic, and then adopted on a more permanent basis in large part due to sustained advocacy from campaign groups. IDC has heard accounts from people subject to reporting requirements that this shift has helped ease in-person reporting requirements that were onerous, expensive and disruptive to their livelihoods and schooling. Moreover, places such as police stations and reporting centres often cause people increased anxiety that they will be redetained; limited physical contact with such places is likely to have a positive impact on people’s mental health and wellbeing.

Of course, as one of the groups campaigning for this change stated, “[t]elephone reporting itself could be equally burdensome if implemented without care.” It is essential that people are provided with the means to report in this way (for instance with support to buy a telephone and credit), and that the consequences for missing a call are not harsh; otherwise, this type of reporting can have negative impacts on people. Moreover, whilst the use of phones is a relatively rudimentary form of technology, it is important that tools such as voice or face recognition are avoided for the reasons mentioned above.

Lived Experience of Tech-Based ‘ATD’

IDC’s main impetus for launching this new workstream on technology, immigration detention and ATD has come from our members, and in particular the experiences and insights of leaders with lived experience and community organisers on the ground who we engage with on an ongoing basis. Through this workstream, in particular, we hope to explore the impact that this technology is having on people’s lives, wellbeing, and futures. Since our founding almost 15 years ago, IDC has been advocating for ATD as a way of moving towards migration governance systems that do not use detention and – crucially – ensure that people on the move have the agency and the ability to meaningfully engage with such systems.

Therefore, we hope to understand not only how tech can be harmful to people on the move, but also if and how it can help to increase positive and meaningful engagement. This will help IDC to better assess how to partner with others to push back on certain types of technologies, and also where innovations might open up opportunities for people with lived experience in terms of improvements to services, information provision, and communication. This will include looking at the impact of digital technologies through an intersectional lens, and understanding that people’s diverse and intersecting identities mean that their experiences of such technologies vary greatly.

Accountability & Due Process

Last but not least, the question of accountability – and the distinct but related issue of due process – is one that we are hoping to explore through this programme of work. Use of AI and tech in the migration governance sphere is notorious for lacking transparency, which is potentially very harmful, particularly when methods are being implemented towards people who struggle to access their fundamental rights and legal recourse. Additionally, ATD themselves can lack key safeguards that allow for due process. The right to appeal and review a decision to detain is often expected in detention (whether or not it is respected in practice), however the same is not necessarily true when somebody is placed in an ATD programme. Where restrictions are imposed, including those linked to digital technology, these should be subject to rigorous review, and the right to appeal should be standard.

When technology is used to increase people’s freedom of movement and ability to access information, as well as to increase their agency and support their empowerment, it has the potential to uphold key human rights and standards. However, when the primary purpose of digital technologies is to expand surveillance and enforcement-based monitoring, it has the opposite effect and leads to the curtailment of rights and freedoms. Unfortunately, given the increasing tendency of many states across the world to adopt migration governance systems based on criminalisation, coercion, control, and deterrence, their growing use of technologies risks exacerbating what are already restrictive, harmful and unaccountable systems.

IDC will learn and build upon some of the excellent research that already exists, and we will compile resources and develop insights for our members and partners. Our ambition is that, by getting to grips with this issue, we can support the growing movement to ensure that use of technology in the immigration detention and ATD space does not lead to a further erosion of human rights and dignity for migrant, refugee, and asylum seeking communities.

Written by Hannah Cooper IDC Europe Regional Coordinator and Carolina Gottardo IDC Executive Director. IDC would encourage anyone interested in collaborating on this workstream to get in touch with us; we look forward to connecting with others on this crucial issue.

Beyond the 2022 IMRF: What’s Next?

The May 2022 International Migration Review Forum (IMRF) was a critical moment to connect local, national, regional and global advocacy efforts, and represented a key milestone towards building momentum on ending child immigration detention and prioritising alternatives to immigration detention (ATD). It also presented an opportunity for the migration sector to shape the global narrative of civil society advocacy, and to set a foundation to focus on the rights of migrants and national level change for the next four year cycle ahead of the next IMRF in 2026, as discussed in IDC’s Approach During the IMRF and Beyond.

Since the adoption of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM) in December 2018, there has been an incredible amount of work accomplished to build on the adoption of the GCM under a whole-of-society approach, including by civil society groups and organisations, governments, local authorities, UN agencies and other stakeholders. For example, the UN Network on Migration was established in 2018 “to ensure effective, timely and coordinated system-wide support to Member States” in their efforts to implement the GCM. Building a functioning system of support at national, regional and global levels has been a key priority for the UN Network on Migration over the past four years.

Within the UN Network on Migration, IDC is proud to co-lead, with UNHCR and UNICEF, the Working Group on ATD which is tasked with promoting the development and implementation of non-custodial, human rights-based ATD in the migration context, in line with Objective 13 of the GCM. Working Group members include representatives of civil society organisations, migrant communities, young people, local governments, and UN agencies working on immigration detention issues and ATD across the world. The Working Group has developed a set of technical guidance and snapshots on ATD, and has steered, in collaboration with the governments of Thailand, Portugal, Colombia, and Nigeria, three global peer learning exchanges on ATD in recent years. IDC also co-leads the UN Migration Network Group working group on ATD in the Asia Pacific, as well as co-leads working groups at the national level to implement Objective 13 of the GCM. These efforts, such as linking national, regional and global initiatives, are part of a long-term movement to reduce and ultimately end immigration detention, and resulted in detention and ATD being key priorities for States to address during the IMRF (also view the IMRF press conference by the President of the General Assembly to hear more about the priorities, including ATD).

What actually happened at the IMRF?

During the IMRF, some States, including Colombia, Mexico, Germany, Thailand, among others, made pledges regarding ending child immigration detention and promoting best practice on this matter. IDC supported in drafting some of these global pledges, which was a process that exemplified the importance of sustained advocacy, collaboration and strategic government engagement at global, national and local levels, as well as the GCM principles of whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches. The UN Network on Migration has launched The Pledging Dashboard to collate State commitments in the implementation of the GCM. Please review and see if your government has made a pledge!

With regards to immigration detention and ATD, both issues were featured quite extensively in State and multi-stakeholder discussions throughout the IMRF. This included commentary on concerns about the increasing and aggressive use of immigration detention in many regions of the world, as well as analysis of progress being made to promote ATD more widely and to work to end child immigration detention. In particular, child immigration detention was a centrepiece of detention-related discussion, and proved to be quite contested in the negotiations and eventual adoption of the 2022 IMRF Progress Declaration. While the GCM itself includes actionable commitments to work to end child immigration detention, some States attempted to now soften this commitment through the negotiations of the Progress Declaration. However, through the multi-level, multi-stakeholder advocacy of IDC and its partners at the IMRF, and the effort of some champion countries, the issue was indeed advanced in the Progress Declaration and included States determination to “consider, through appropriate mechanisms, progress and challenges in working to end the practice of child detention in the context of international migration.”

Key IMRF Takeaways

For IDC, the framework for moving forward beyond the 2022 IMRF will involve coordinating a multi-level agenda that uses national, regional and global momentum to make change on the ground and that centres the rights of migrants in all GCM implementation efforts. Particularly key for IDC in the next period, in our role as a convener of multi-level peer learning, is ensuring connection, coherence and coordination between national, regional and global efforts, which will allow us to enhance whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches in the interest of change. The key takeaways from the 2022 IMRF that will support and guide our work across all levels include:

1. Global Visibility of Immigration Detention & ATD

Following much political turmoil in various global and regional processes over the years - addressing the use of immigration detention, working to end child immigration detention and the promotion of ATD are now solid components of the global migration agenda through the GCM. This is an important win, and resulted from the sustained strategic engagement and narrative shifting performed by many actors across various spaces. The next step is to use this global affirmation to enhance and leverage national action and change that results in tangible protection of migrant rights towards a world without immigration detention.

2. Multi-Level Peer Learning as a Key Approach

Through the UN Network on Migration Working Group on ATD and regional Platforms such as a the Regional State Platform in the Asia Pacific , IDC and its partners have coordinated and led peer learning processes for government actors over many years. IDC advanced this particular methodology across local, national, regional, and global levels through the development of communities of practice. This method has now been integrated into the Progress Declaration and officially recognised as a mechanism for analysing progress, “...calls on the Network to cooperate with Member States and relevant stakeholders to strengthen collaboration, peer-learning, engagement and linkages at global, regional, national and local levels.”

3. Centering Grassroots & Lived Experience Leadership

While purposeful efforts have been made to address the limited adequate mechanisms for engaging civil society in UN and global processes, particularly directly impacted people and communities - this is a systemic issue that requires a systemic solution. An entire mindset shift regarding leadership, equity, and accountability is needed to transform these systems and ensure meaningful participation and representation moving forward. As discussed in IDC’s article in the Spotlight Report on Global Migration, “Migrants give life to these issues, and are key to making this necessary transformation in collaboration with different stakeholders, including government allies. To end immigration detention we will need the same perseverance and determination as those who have survived detention. And if we work together with solidarity, understanding, and with a genuine desire to make a change, we can achieve it (page 19).”

Moving Forward

IDC alongside our members and partners in the coming period, will focus on ensuring implementation of the pledges made at the IMRF, expanding advocacy on ending immigration detention beyond ending the detention of children, continuing to connect local, national, regional and global agendas, facilitating and coordinating strategic peer learning spaces, and centering the leadership of people with lived experience of detention in all of our efforts.

The focus of the UN Network on Migration moving forward will be national implementation, including the development of national action plans by governments. As such, all of our roles in actualising the GCM are most important now that we are beyond the 2022 IMRF. As civil society, we must be ready to organise, engage, and advocate to ensure governments are living up to their GCM commitments on the ground. There will be an Annual Meeting of the UN Network on Migration in October 2022, where these priorities will be discussed and a new work plan for the Network will be developed with the input of civil society and other actors. Additionally, IDC aims to enhance the Working Group on ATD exchange space by redesigning it to more effectively connect national, regional and global levels in order to increase our collective ability to give life to the GCM. This will involve creating a more diverse and dynamic membership for the Working Group in the upcoming period. Additionally, we will continue with our work as co-leads of the ATD Working Group in the Asia Pacific and with the Regional Networks in other regions; and also continue co-leading relevant working groups and participating in UN Migration Network national efforts in selected GCM champion countries. Key to this agenda will be the effective coordination and connection between national, regional and global initiatives aiming to implement Objective 13 and promote ATD to ultimately end immigration detention. Please contact IDC Global Advocacy Coordinator Silvia Gómez [email protected] for more information and to explore possibilities for engagement.

Lastly, four months after the IMRF, IDC will host an event on 21st September 2022, to launch our global mapping report Gaining Ground: Promising Practices to Reduce and End Immigration Detention and our Asia Pacific report Immigration Detention and Alternatives to Detention in the Asia Pacific Region, which was developed in collaboration with the Regional UN Network on Migration for Asia and the Pacific under the umbrella of the UN Network on Migration.

REGISTER and join us to hear from experts at local, national, regional, and global levels about how to use this new research to scale up rights-based ATD and further advocacy to reduce and ultimately end immigration detention, including by supporting improved implementation of the Global Compact for Migration (GCM).

Written by Carolina Gottardo Executive Director, Silvia Gómez Global Advocacy Coordinator & Mia-lia Boua Kiernan Communications & Engagement Coordinator

IDC’s Approach During the IMRF & Beyond

In December 2018, 164 States signed the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM). This followed 18 months of negotiation among the UN General Assembly, during which States came together to discuss migration challenges and solutions. Civil society, including IDC, supported States in this process and advocated for them to take particular positions on various issues, such as immigration detention, alternatives to detention (ATD), and ending child immigration detention. The GCM is the official written result of these governmental exchanges and negotiations, and is the world’s first intergovernmental agreement covering all areas of international migration. While non-binding, the GCM provides governments with a UN policy framework for ensuring rights-based migration experiences across the world, more information here.

The GCM includes 23 Objectives which address a wide array of areas within the migration experience, such as regularisation pathways, access to services, discrimination issues, preventing loss of life, labour rights, human trafficking and many more. For IDC, Objective 13 aligns with our mission to reduce and end immigration detention: Use migration detention only as a measure of last resort and work towards alternatives (read the full text of Objective 13 on pages 20-21 of the GCM here.)

IDC was an integral civil society actor in the process of developing and ensuring that Objective 13 reflected existing human rights standards and obligations, and offered a solutions-focused way to action commitments. IDC and partners strategically negotiated and collaborated with different government actors to secure inclusion of particular provisions within Objective 13, including commitments to work towards the end of child immigration detention, to prioritise ATD, and to ensure a human rights-based approach to GCM implementation. While IDC and our partners had even stronger commitments that we wanted on these issues, the resulting Objective 13 in 2018 helped to set concrete milestones for our continuing advocacy towards ending immigration detention for all, particularly through holistic and collaborative whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches that centre impacted migrant communities and leaders with lived experience of detention.

The IMRF

Now, four years later, the UN General Assembly is convening the International Migration Review Forum (IMRF), which will formally review the progress of governments and stakeholders in implementing the commitments and principles stated in all of the GCM Objectives. This review will happen every four years, with the inaugural IMRF taking place from 17-20 May 2022 in New York City. Further, States have agreed that each IMRF will produce a Progress Declaration - an official document outlining efforts made towards enacting the GCM framework over the four-year period being reviewed, including suggestions for moving forward and improving progress.

For IDC, a key aim in the lead up to and during the first ever IMRF has been to influence the drafting of this Progress Declaration, particularly in relation to the implementation of Objective 13. To do this, we have been working in close collaboration with civil society partners, leaders with lived experience, UN agencies, governments, local authorities, and other stakeholders invested in this global process, including the State co-facilitators of the IMRF and the Progress Declaration negotiations, Luxembourg and Bangladesh. IDC and partners have been advocating to integrate the following key actions related to Objective 13 into the 2022 Progress Declaration:

- Uphold the GCM guiding principles and ensure there is no regression from the GCM adopted in 2018

- Acknowledge the steps taken by States, civil society actors, and other stakeholders to progress Objective 13 over the past 4 years

- Acknowledge the critical role of migrant communities and ensure full and meaningful participation and collaboration

- Include concrete and practical guidance to phase out immigration detention, and implement rights-based and community-centred ATD where applicable

- Solidify opportunities for peer-learning to enhance international cooperation, whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches

- Build on progress and strengthen the path towards ending child immigration detention that also leads the way to ending immigration detention for all

What happens during the 4 days of the IMRF?

The IMRF is a process led by States and convened by the UN General Assembly, therefore the agenda includes a set of plenaries geared towards facilitating exchange between States. An Interactive Multi-stakeholder Hearing for civil society and other stakeholders will take place on 16 May, as well as four thematic Roundtables on 17 and 18 May covering each of the 23 GCM Objectives. Anyone can view these roundtables, broadcasted here, while those registered and attending can join in person. IDC’s Executive Director Carolina Gottardo will moderate Roundtable 2, which includes Objective 13. Summaries of all four roundtable discussions are then shared in a policy plenary on 18 May, which will also showcase successes, challenges, and gaps in GCM implementation. Finally, on 20 May, the last day of the IMRF, the Progress Declaration will be adopted by Member States.

Further, civil society, UN agencies, governments, local authorities and other stakeholders will host side events during the IMRF to maximise momentum and engagement on various issues. In IDC’s role as co-lead of the UN Network on Migration Working Group on Alternatives to Detention alongside UNICEF and UNHCR, we are co-organising a side event with the governments of Thailand, Portugal, and Colombia. This 19 May panel event will focus on ending child immigration detention, and feature long-time IDC partner Hayat Akbari, a campaigner and advocate with lived experience of child detention, alongside government and UN representatives, and IDC’s Executive Director Carolina Gottardo who will provide insight into upcoming IDC research on detention and ATD. This is an online event, and we cordially invite those interested to join us here.

The UN Secretary General has also commenced a Pledging Initiative, which encourages States, UN agencies, civil society, and other stakeholders to pledge “a measurable commitment to advance the implementation of one or more GCM principles, objectives or actions.” Civil society can engage governments for pledges, which can be submitted here for presentation during the IMRF, and then used to support ongoing advocacy. IDC has been engaged in this initiative by supporting some governments with their pledging processes.

IDC’s Approach During the IMRF & Beyond

For IDC, the IMRF is a key milestone towards building momentum and furthering the global movement to end immigration detention. We do this through analysing the progress, gaps and challenges experienced by governments, civil society, communities, and other stakeholders in implementing Objective 13. Through reflection and taking stock, we identify promising developments, and agree on ways forward to strengthen and expand practices towards ending immigration detention.

To this end, IDC engaged in a series of research initiatives over the past few months, and will release three reports on immigration detention, ATD and Objective 13 implementation:

- Gaining Ground: Promising Practice to Reduce and End Immigration Detention - a global mapping that overviews promising ATD practices across the world

- Immigration Detention and ATD in the Asia Pacific Region - a UN Network on Migration collaboration providing insights on regional promising practice

- An IDC and UNICEF MENA collaborative mapping report identifying promising practice to end child immigration detention in the region

This strong and new evidence-base creates a catalyst for invigorating targeted peer-learning at regional and global levels, as well as exchange of technical expertise within and across regions, which will make IDC and our members and partners more impactful on the ground. Since its inception, IDC has prioritised the development of national, regional and global communities of practice that aim to change legal frameworks, policies and practice, and build more effective government and civil society partnerships through a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach. IDC’s new research provides cutting-edge knowledge that can be used to make collaborative change through concrete action. This strengthens existing communities of practice and peer learning exchanges, and ultimately supports governments in implementing Objective 13 by looking into promising developments and addressing challenges and gaps.

More broadly, the IMRF gives all of us in the migration sector an opportunity to shape the global narrative of civil society advocacy. We identify the wins and losses for ourselves, and ensure that communities affected by migration policies are provided with the opportunity to lead in advocacy that directly impacts their own lives. Global events such as these are best utilised when civil society engages to showcase and build our collective expertise across the world. In particular for IDC, the IMRF is a critical moment to connect local, national, regional and global advocacy, and ensure that grassroots expertise and leaders with lived experience of detention are centred at each and every level.

As the focus moving forward will be strongly placed on national implementation, including further promoting voluntary national reviews of implementation and the development of national action plans by governments, all of our roles in actualising the GCM are most important beyond the 2022 IMRF. Civil society must be ready to organise, engage, and advocate to ensure governments are living up to their GCM commitments on the ground. While the IMRF is an opportunity to reflect and take stock, it is also an opportunity to envision and plan for strengthening and scaling up progress in the years to come, and ensure that real impact on the lives of migrant communities is at the centre of our changemaking.

For continued updates on the IMRF, please subscribe to the UN Network on Migration newsletter here, and view live streaming coverage of the IMRF in UN official languages at the UN TV website here. Please also contact IDC Global Advocacy Coordinator Silvia Gomez [email protected] for more information.

Written by Carolina Gottardo Executive Director, Silvia Gómez Global Advocacy Coordinator & Mia-lia Boua Kiernan Communications & Engagement Coordinator

IDC Statement on the Crisis in Ukraine

Published on Friday 4 March, 2022

It’s been just over a week since the Russian government initiated a military invasion of Ukraine, and civilians are continuing to flee their homes in response to ongoing airstrikes, shelling, and ground fighting. According to the United Nations, as of 2 March more than one million people had fled the country in search of safety, many on foot in bitter cold temperatures - including tens of thousands of families with young children and infants. International Detention Coalition (IDC) stands firmly in solidarity with all those who have been impacted by this conflict, and we unequivocally condemn the Russian military invasion of Ukraine.

The largest numbers of refugee arrivals have been seen in Poland, Hungary, Moldova, Slovakia and Romania. The response of these governments has so far been overwhelmingly positive, with the Polish Interior Minister declaring that the country would take “as many [people] as there will be at our border,” and both the Hungarian and Moldovan governments pledging to keep their borders open to those fleeing the conflict in Ukraine. Local communities have also shown great generosity and hospitality; nine out of every ten refugees in Poland are being hosted by friends or family.

At the EU level, on Thursday the decision was taken to offer temporary protection to refugees fleeing Ukraine by triggering the temporary protection directive, which was drawn up in 2001 following the conflicts in the Balkans but has so far never been used. The Directive allows for people fleeing a particular country or area to be granted status for up to three years, without having to formally lodge an asylum claim. Other countries across the world have also shown their support for those affected by the conflict.

For IDC and its members, this positive response provides further evidence that immigration detention is not a necessary or integral part of migration governance systems at all. When governments prioritise creating a welcoming and safe environment for those fleeing war and persecution, people can seek sanctuary without being detained, and crucially with their human rights and liberty intact.

However, concerning reports have emerged of African migrants and other migrants of colour, including international students studying in Ukraine, being blocked or delayed from fleeing to safety. This is unacceptable. Moreover, at its border with Belarus the Polish government continues its project to construct a wall to deter migrants and those seeking asylum from crossing. This follows months of aggressive pushbacks by the Polish authorities of people seeking safety, many of whom are migrants of colour, which have led to the deaths of at least 19 people. Regardless of sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, and racial, ethnic, religious, and national background, it is essential that all those fleeing conflict are able to exercise their right to seek asylum and their right to freedom of movement. Governments of receiving countries must provide a welcoming atmosphere, documentation and access to services to those arriving in search of peace and safety from Ukraine and elsewhere.

Overall, the regional and international response to the crisis in Ukraine has so far demonstrated that “Refugees Welcome” can be more than a slogan. As the crisis continues to unfold, IDC urges all governments to sustain the support and assistance that they have generously extended to so many fleeing Ukraine, and ensure this support is delivered to all people with equity and compassion. We also encourage governments to learn from this situation in order to inform their future responses to war and crises which force refugees and migrants to seek safety at their borders – no matter where people are from.

To the people, families and communities whose lives and futures have been impacted and uprooted by the conflict in Ukraine, we stand with you during this heartbreaking and challenging time.

IDC members are actively responding to refugees arriving from Ukraine:

- In Poland, The Association for Legal Intervention (Stowarzyszenie Interwencji Prawnej - SIP) works to ensure that migrants and refugees in Poland are able to access their rights. See here for more information on accessing legal support and crossing the border into Poland. Other information can be found in Polish, Ukrainian, Russian and English here.

- In Romania, the Jesuit Refugee Service is providing support to people arriving from Ukraine by providing welcome packages, channelling donations to people in need, and supporting people with accommodation and onward travel. Find out more and donate here.

- In Hungary, the Hungarian Helsinki Committee is providing support and legal assistance to those fleeing Ukraine. They have produced information packs for refugees in Hungarian, Ukrainian, Russian and English that can be accessed here. For more information on their response and to donate, click here.

More information on the ongoing crisis, and regular situation updates, can be found on the UNHCR Help page and the Operational Data Portal for Ukraine.

COVID-19 Impacts on Immigration Detention: Global Responses

Over the past few months, immigration detention practices around the world have been changing rapidly as state and civil society actors respond to manage the multiple impacts of COVID-19. In some cases, these changes have been positive, leading to stronger protection of the rights of non-citizens. In others, they have led to the increased marginalisation of and discrimination against non-citizens.

In collaborating with the Humanitarian and Development Research Initiative to produce this joint edited collection, the International Detention Coalition sought to provide a platform for our members and partners to discuss their experiences, actions and perspectives as the pandemic unfolded across the globe. The contributions are rich and diverse, showing the impact that COVID-19 has had on refugee, undocumented migrant and stateless communities around the world.

The contributions also speak to rising levels of inequality. States with already weak healthcare systems before the pandemic struggle to manage rising caseloads. Civil society groups have had to cut back on their activities in the light of increased restrictions and health concerns; funding shortages have jeopardised the continuity and reach of their essential services. Migrants, stateless persons and refugees in overcrowded housing have been unable to practice physical distancing and, against rising xenophobia and racism, have been susceptible to scapegoating for the impact of COVID-19. In many contexts, the health and welfare of citizens has taken firm precedence over that of these groups.

COVID-19 does not discriminate, but laws, policies and practices concerning migration governance, immigration detention, and public healthcare shape the vulnerability of migrants, stateless persons and refugees to its spread and effects. The contributions in this joint edited collection highlight both positive and negative developments over the past year that need careful attention – and in some cases, urgent correction – for the health and wellbeing of all..

We extend our gratitude to the authors for their contributions, which have allowed the breadth of responses that are in this collection. We also thank HADRI, and in particular Dr. Melissa Phillips, who is also part of the IDC’s International Advisory Committee, for the opportunity to have collaborated on this important initiative.

Alice Nah Chairperson of the Committee, IDC

COVID-19 Impacts on Immigration Detention: Global Responses - Available for DOWNLOAD TODAY

ATD for Migrant Children in Mexico

Over the past few months, IDC has participated in discussions with the local authorities of various Mexican states regarding strategies for alternative care, aimed at strengthening the local implementation of the Migrant Child Protection Protocol.

This was done through the Commission for the Protection of Migrant Children and Asylum Seekers. In this video, Diana Martínez, Americas Programme Officer, explains the concept of alternatives to detention and its relation to alternative care for migrant and refugee children. She also presents experiences from other parts of the world, which were identified by IDC as good practices.

(Available in Spanish)

Opportunities Amidst the Pandemic

Preventing the detention of migrant children through local coordination of a national protection route

The government of Mexico ended 2019 with a huge debt due to depriving 51,999 migrant children of their liberty, a 77.7% increase compared to the previous year. In response to the prohibition contained in the Regulations of the General Law on the Rights of Children and Adolescents, which states no minor under the age of 18 shall be detained for migratory reasons, the Commission on the Protection of Migrant Children and Adolescents (Protection Commission) began 2020 with a plan to implement the recently created Protection Route for Children and Adolescents in a Mobility Situation, with the support of civil society members of this commission.

Although the health emergency interrupted the progress in coordination and implementing priorities, as in many countries, the use of technology has allowed the continued coordination of care and advocacy of civil society organisations to gain the right to personal freedom for migrant children and adolescents. The Protection Commission adjusted and reorganised its work to account for the health emergency, while also implementing the urgent Protection Route throughout the 32 states in the Mexican Republic. This was done with the central aim to not use immigration detention, and to provide referrals to several models of alternative care focused on case management.

Covid-19 caused sudden full migration stations in Mexico, including the presence of migrant children and adolescents. Unfortunately, they were not freed by immigration authorities into emerging programs on alternatives to detention; instead, many were transferred to their countries of origin, whenever border restrictions permitted. Faced with this worrying scenario, the Protection Commission launched a virtual conversations program aimed at listening to the needs of state authorities, and local civil society organisations to create a national response to the pandemic. Furthermore, the ultimate purpose was to make sure each state established a similar commission tasked with implementing the Protection Route, and the promoting alternative care models for migrant children and adolescents.

The first conversations session had nationwide reach with over 140 participants, mostly child protection, migration and asylum authorities who spoke about the recommendations issued by international bodies on effective protection of migrant children and adolescents in the context of Covid. IDC shared the Recommendations of the Working Group on Alternatives to Immigration Detention of the United Nations Network on Migration, which seek to ensure the health of people in human mobility situations who are detained or at risk of being detained. These recommendations include: ending immigration detention, adopting moratoriums on the use of immigration detention, and increasing non-custodial alternatives to immigration detention.

This conversation session has been followed by more exchanges with local authorities in the states of Chiapas, Baja California and Coahuila, which emphasised the need for better coordination among child protection authorities and immigration and asylum authorities. Better coordination will ensure that children and adolescents in mobility situations are not deprived of their liberty at migration stations. Some alternative care models have been presented during these session, and civil society has shared the obstacles to adopting the Protection Route, with an emphasis on case management. This will be followed by conversation sessions with the states of Tlaxcala, Sonora and others.

Mexico continues to face significant challenges to protect children and adolescents in a mobility situations, such as the difficulty of coordinating authorities. There are over one thousand protection authorities in the country with powers to care for migrant children and adolescents. Additional difficulties include lack of resources, and the power conferred by law to immigration authorities to place children and adolescents in migration stations prior to being referred to protection officials.

The efforts made by the Protection Commission, supported by IDC and its member and allied organisations, has led to the possibility of developing effective models, establishing coordination mechanisms, and generating data and evidence on better care for children and adolescents. At its core, this is about ensuring the freedom of this population, and making referrals to alternative care models that allow them to live in the community, and with the support of various entities that enable the fulfilment of their human rights.

Successful GFMD Event, Quito: Alternatives to Child Detention

During the last Global Forum on Migration and Development in Quito (GFMD) Summit, which took place in Quito from the 20th to the 24th of January 2020, a side event organized by IDC and UNICEF under the umbrella of the Cross-Regional Peer Learning Platform on Alternatives to Child Immigration Detention brought together over 60 representatives from States, local governments, civil society organizations, trade unions, youth organizations and UN agencies to discuss challenges and share progress in developing alternatives to child immigration detention.

Ranging from State representatives and local authorities to civil society organizations and UN agencies, interventions from participants to this roundtable exchange showcased how peer learning, whole-of-government collaboration and engagement from all relevant actors can effectively support States in moving forward progress and overcoming challenges when implementing alternatives to child immigration detention.

Side event organized by IDC and UNICEF under the umbrella of the Cross-Regional Peer Learning Platform

Speakers shared current practices and ongoing efforts, discussed challenges and setbacks and identified opportunities for cooperation at local, national, regional and cross-regional level.

Ending child immigration detention is possible. There are alternatives and this side event showed that there is a strong appetite to make the global consensus on the need to work to end the use of migration-related detention for children and families a reality in practice.

Following the roundtable discussion attendees engaged in a fruitful exchange on opportunities for peer learning, targeted support, international cooperation and collaborative work under the umbrella of the Cross-Regional Platform, a pioneering multi-stakeholder global initiative facilitated by the IDC in collaboration with UNICEF. 2020 will see the first Global Peer Learning Meeting on Alternatives to Child Immigration Detention which will be convened by the facilitators of the Cross-Regional Platform in cooperation with the UN Migration Network.

If you are interested in knowing more about the development of the Cross-Regional Platform see here and/or contact IDC's Global Advocacy Coordinator, Silvia Gómez [email protected].