An Exploration of Accommodation Provision for Migrants in the EU

This blog is written by Rositsa Atanasova, Advocacy Expert at the Center for Legal Aid – Voice in Bulgaria, a European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN) member and ATD pilot implementer, and overviews the results of an EU mapping which demonstrates a wide variety of options when it comes to accommodation provision for migrants, including those that could be used within designated ATD initiatives.

In many national contexts the application of alternatives to detention (ATD) remains limited in practice, because detention is applied by default to foreign nationals who have lost the right of residence, and not as a measure of last resort. According to EU and international law, states must consider ATD before depriving people of their liberty. Yet too often we see an improper reversal of the burden of proof, whereby it is up to people in irregular situations to contest the presumption of detention by proving that they fulfil the requirements for the application of alternatives.

In Bulgaria, the experience of the Centre for Legal Aid – Voice in Bulgaria (CLA) is that there is almost no individualised assessment of the principles of necessity, reasonableness and proportionality, as required by European and international legal standards. Instead, authorities are only willing to consider ATD when an individual has met the conditions in the law for the implementation of alternatives through case management support. Frequently, this includes a requirement that suitable accommodation be available.

In order to better understand current accommodation options in the EU and Bulgaria, as well as their potential for expansion in the context of ATD, in late 2021 I carried out a study on options for irregular migrants. Here, I explain my conclusions as well as the implications when it comes to ATD for people in immigration detention.

Accommodation Options for Irregular Migrants in the EU

The study of accommodation options for irregular migrants, which I conducted for CLA with the support of our donor EPIM, consists of a mapping paper and an advocacy strategy. The mapping paper systematises current practice in the EU and advances a new conceptual framework for analysis of the link between ATD and accommodation. It is based on desk research and fills a gap in recent research on the accommodation of irregular migrants in the EU. The advocacy document, in turn, explores current practice in Bulgaria and contains an action plan for the short and mid-term in order to improve access to accommodation and expand the use of ATD. It draws on meetings with a range of stakeholders including government agencies and local authorities, NGOs, service providers and beneficiaries. The interviews provided information about the range of existing services, which was not available through desk research alone.

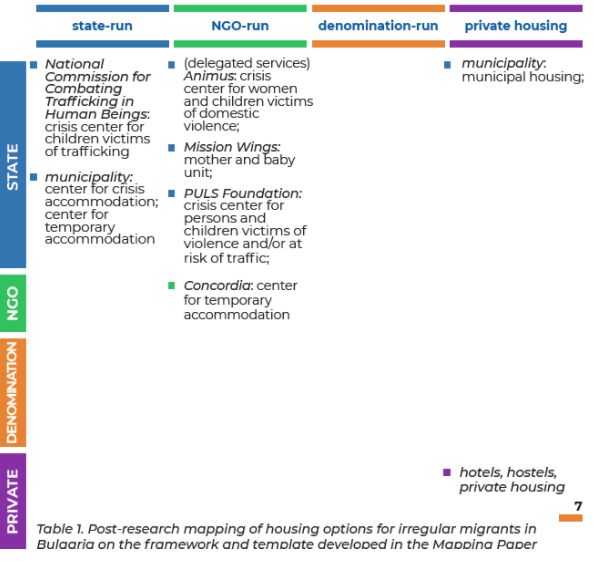

The range of accommodation options for irregular migrants in the European context can be mapped on a matrix (Table 1) in relation to the nature of the service provider and the nature of any potential partner. The axes represent a spectrum of accommodation provision, from state-run housing to private accommodation through NGO and denomination-run residential options. Such a model allows us to visualize dependency on an intermediary to access accommodation alternatives and how much of that service-provision is dominated by the state. In addition, the chart illustrates potential new areas for service-creation that might not yet exist. The matrix is ultimately also an instrument for measuring whether responses are mostly community-based or institutional.

As illustrated by the examples above, accommodation for irregular migrants in the EU, if available at all, tends to be institutional and oriented towards return. In exceptional circumstances, people who cannot be deported to their country of origin can be accommodated in open reception centres for asylum-seekers or in homeless shelters. These options, however, are not presented as possible ATD, but as a way for authorities to provide a bare minimum of material assistance. The different housing possibilities presented here are most often used by irregular migrants who are not in contact with the authorities. Such pathways, however, can be quickly and usefully deployed to offer alternatives to detention in an emergency situation, as illustrated by regularisation initiatives during the pandemic. This is why it is useful to consider the full range of available choices in an effort to expand the ATD portfolio.

Accommodation Options for Irregular Migrants in Bulgaria

The study of accommodation options for irregular migrants in Bulgaria reveals a gradually shrinking space, however. Access to state services, State Agency for Refugees (SAR) reception centers and municipal housing have become more difficult to access even for beneficiaries of international protection, not to mention those in an irregular situation. Service providers are less willing to bend the rules to accommodate people without documents in crisis, particularly in light of pandemic measures. Mothers with children and victims of domestic violence or trafficking are the only groups that face fewer impediments, but even their access frequently involves protracted negotiations with service providers and social workers to renew referrals on a case by case basis. Placement in a service, ultimately, does not qualify as a formal ATD, but amounts to tolerated stay that is not formalized in any way.

Private housing remains the most readily available option for irregular migrants and the only one that currently qualifies as a formal ATD. The advantage of the Bulgarian system is that those who lend property to people without documents do not seem to incur criminal or administrative sanctions, in line with FRA recommendations. As a downside, private arrangements are onerous due to the need to find a guarantor who is willing to provide financial support, as well as to locate suitable accommodation amidst exploitative renting schemes, discrimination and limited choices.

Implications for ATD

The results of the mapping and advocacy strategy, outlined above, demonstrate a wide variety of options when it comes to accommodation provision for migrants, including those that could be used within designated ATD initiatives. On the face of it, the Bulgarian accommodation requirement mentioned above could potentially be good news because it opens up the space for NGOs to develop accommodation options and case management programs for irregular migrants in order to expand the use of ATD for those at risk of immigration detention. Moreover, we know how essential stable and appropriate accommodation is for those going through migration processes; the government requirement could be seen as a recognition of this. By drawing on lessons learned across the EU, and developing additional accommodation models, the implication is that advocates for the rights and liberties of migrants can encourage a shift on the part of governments to using ATD.

The reality, however, is more complex. Given the standing presumption of detention in Bulgaria, it is not clear whether the availability of more housing options for irregular migrants will necessarily lead to greater application of alternatives. Instead, it seems that the accommodation requirement is being used as an excuse to justify the government’s failure to systematically consider ATD, linked to a general political resistance to community-based solutions (including on national security grounds).

CLA practice indicates that authorities tolerate stay in services when it will spare them the responsibility for vulnerable individuals and are more willing to apply ATD when presented with ready-made solutions. The implication, therefore, is that whilst accommodation remains a key part of ATD programmes, the provision of more accommodation options alone is unlikely to be the catalyst for change that it might seem at first glance to be. Provision of accommodation, whilst a key part of ATD, is certainly not a silver bullet. Instead, the reversal of the ATD logic – which sees detention as the primary precautionary measure, as opposed to a measure of last resort – should be challenged on its own terms. In particular, it is essential that the burden of proof is turned back around so that presumption of liberty, rather than detention, becomes the norm. In Bulgaria, possible routes lie in advocating for access to services on the basis of the new Law on Social Services, which is theoretically applicable to all persons within the jurisdiction, and NGOs stepping in as mediators, guarantors or service providers for irregular migrants.

IDC is a co-coordinator of the European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN), and this blog was originally posted on the EATDN site here. Find out more about the work of Centre for Legal Aid – Voice in Bulgaria, including their pilot ATD programme here.

The Action Access Alternative to Detention Pilot: Evaluation of Community-Based Support

An independent evaluation of the pioneering pilot project delivered by European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN) member Action Foundation and funded by the UK Home Office has found it is more humane and significantly less expensive to support women in vulnerable situations in the community as an alternative to keeping them in detention centres. In this blog, Action Foundation Chief Executive Duncan McAuley summarises the pilot, its aims, and the findings of the evaluation.

In 2018, the UK Government published the Shaw Progress Report, a follow-up to the Review into the Welfare in Detention of Vulnerable Persons produced by Stephen Shaw, former Prisons and Probations Ombudsperson for England and Wales. Amongst other recommendations, the progress review urged the UK Government to “demonstrate much greater energy in its consideration of alternatives to detention.” Shortly after its publication, the Government announced the creation of a Community Engagement pilot (CEP) Series, which set out to test approaches to supporting people to resolve their immigration cases in the community.

Action Access: a civil society-government partnership

Following a successful bid process, Action Foundation – which had played a key role in the advocacy efforts that led to the introduction of the CEP – was granted the contract for the first of the four pilots, and our Alternative to Detention (ATD) project was born. The Action Access pilot ran between 2019 and 2021 and supported 20 women seeking asylum in a community setting in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in the North East of England. With one exception, prior to joining the pilot all of the women had been detained in Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre.

Upon joining the pilot, the women were provided with shared accommodation, received one-to-one support from Action Foundation staff, and were supported to access legal counselling. Although it wasn’t a requirement of the pilot, the women also benefited from Action Foundation’s broader program of activity such as its free English language classes and weekly community gatherings, facilitating socialisation, signposting and referrals.

The pilot was framed around five pillars of support:

- Personal stability: achieving a position of stability (in relation to, for example, housing, subsistence and safety) from which people are able to make difficult, life-changing decisions;

- Reliable information: providing and ensuring access to accurate, comprehensive, personally relevant information on UK immigration and asylum law;

- Community support: providing and ensuring access to consistent pastoral and community support, addressing the need to be heard and the need to discuss their situation with independent and familiar people;

- Active engagement: giving people an opportunity to engage with immigration services and ensuring that they feel able to connect and engage at the right level, enabling greater awareness of their immigration status, upcoming events and deadlines with routine personal contact fostering compliance; and

- Prepared futures: being able to plan for the future, finding positive ways forward, developing skills in line with their immigration objectives, identifying opportunities to advance ambitions. Through this approach, the pilot hopes to provide more efficient, humane and cost-effective case resolution for migrants and asylum seekers, by supporting migrants to make appropriate personal immigration decisions.

The model was innovative in a number of ways. The combination of a holistic approach to case management with comprehensive legal support, for instance, was integral to the delivery of the pilot and seen to make case resolution more likely. In addition, although there have been other examples of ATD in the UK, including an ongoing project run by Detention Action, Action Access was the first time that such a pilot had been built from a formal civil society-government partnership. The relationship between many parts of the Home Office and civil society are often tense, and the pilot represented a leap of faith. But we found the experience of working with the Home Office Community Engagement Team a really positive and productive one. There was a genuine collaborative relationship between the Home Office, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and Action Foundation and this unique partnership demonstrates a model of working that is both dynamic and effective. Importantly, it demonstrates the success possible if the Home Office is willing to replicate this approach in the future.

Evaluating the pilot’s success: Improved wellbeing and reduced costs

The findings of the pilot were officially published in late January by UNHCR, who had commissioned the evaluation. The report, entitled Evaluation of the Action Access Pilot, was researched and compiled by Britain’s largest independent social research organisation, the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen). Commenting on the effectiveness of the pilot, NatCen’s report states:

“Our evaluation found qualitative evidence that participants experienced more stability and better health and wellbeing outcomes whilst being supported by Action Access in the community than they had received while in detention. Evidence from this pilot suggests that these outcomes were achievable without decreasing compliance with the immigration system.”

The evaluation said this provided “a more humane and less stressful environment for pilot participants to engage in the legal review and make decisions about their future, compared with immigration detention. Even when those decisions were difficult and participants had no legal case to remain in the UK, the pilot gave the participants space and time to engage with their immigration options.”

The more humane environment was a repeated theme shared with researchers, with one of the participants saying, “In detention, you don’t have this kind of positive atmosphere. You just want to cry. You just want to stop eating. You just want to kill yourself. This is because you are so in trouble there, right. Then, when you come out, it’s like everything is going to be nice again… the atmosphere is very different, and I think you recover yourself.”

The evaluation of Action Access also suggests that keeping people in the community is much less expensive than holding an individual in detention. The report states that the potential savings could be less than half the cost of detention, in line with Action Foundation’s own calculations.

Next steps: Introducing ATD as ‘business as usual’?

While Action Access may have come to an end, Action Foundation continues to work according to the same model: combining one-to-one case management with comprehensive legal advice in order to ensure that people are able to resolve their cases in the community. We continue to believe that this type of community-based support is the best way of supporting people going through the migration system and can be used effectively instead of detention.

As for the UK Government’s next steps, it remains to be seen what will come of the CEP Series in practice. A second pilot is already underway, run by the King’s Arms Project, however there have been no confirmations that the CEP series will continue beyond this.

The seven recommendations made in the Action Access evaluation, all of which the Home Office has accepted, included a call for them to “accelerate the introduction of effective aspects of the ATD programme into the Home Office’s ‘business as usual’ model.” We hope to see progress on this, and the upcoming International Migration Review Forum (IMRF) could be the perfect context to pledge to take action. In the UK as is the case elsewhere, there’s a growing need for a change of direction and a rethinking of the approach to migration management – particularly when it comes to immigration detention. We hope our pilot, and the evidence that has emerged from it, can contribute to those necessary changes.

IDC is a co-coordinator of the European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN), and this blog was originally posted on the EATDN site here. Also find out more about the Action Access pilot here and here.

IDC & ECDN Welcomes Launch of ATD Pilot in Malaysia

25th February 2022, Kuala Lumpur – The End Child Detention Network Malaysia (ECDN) welcomes the launch of the Alternative to Detention (ATD) pilot programme by the Malaysian Government. The pilot programme is anchored by the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development and the Ministry of Home Affairs. The pilot programme, which will provide temporary shelter for unaccompanied and separated children under detention, acknowledges the serious harms that children face in immigration detention and focuses on prioritising the physical and mental health development of children.

The ATD pilot programme is a step in the right direction towards fulfilling Malaysia’s obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which the nation ratified in 1995, and is timely, as Malaysia prepares to submit a status report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. The standard operating procedure (SOP) framework for the ATD pilot, which was developed in consultation with select non-governmental organisations, is strongly guided by the principle of best interests of the child (Article 3), and further upholds the rights of a child to be protected from all forms of violence (Article 19), and to access special protection in the event of separation from family environment (Article 20). Further to that, the launch of the ATD pilot also works towards the implementation of policies and legislations that promote and protect the rights of the most vulnerable communities - which was one of Malaysia’s pledges made to secure their seat on the United Nations Human Rights Council, and signals Malaysia’s commitment to the ASEAN Declaration on the Rights of Children in the Context of Migration and its corresponding Regional Plan.

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has provided authoritative guidance that immigration detention is a violation of child rights, and as of October 11, 2021, the Home Ministry reported about 1, 425 children in detention centres nationwide. Malaysia has been lagging behind our closest neighbours in ASEAN, specifically Thailand and Indonesia, who have since 2019 released hundreds of children from immigration detention into community-based care. Thus, we welcome the launch of the ATD pilot programme as a step towards ending child detention in Malaysia, and we urge the Malaysian government to follow through in ensuring that all human rights of a child, and a child’s wellbeing and best interests are foregrounded and upheld throughout the process of release, community placement, as well as in our immigration policies. As we move forward, we strongly recommend to the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development and Ministry of Home Affairs to develop a clear framework for monitoring and evaluation of the ATD pilot that focuses on the best interest of the child. We also call on the Malaysian government to provide further details and regular updates on the implementation of this ATD Pilot in Parliament.

We look forward to continuing working with the government, policymakers, and implementing staff to protect and uphold the human rights of all children in Malaysia.

About the End Child Detention Network (ECDN) The End Child Detention Network is a coalition of civil society organisations and individuals working to ensure that no child is detained in Malaysia due to their immigration status.

For more information, please contact: End Child Detention Network Coordinator - [email protected]