IDC’s Approach During the IMRF & Beyond

In December 2018, 164 States signed the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM). This followed 18 months of negotiation among the UN General Assembly, during which States came together to discuss migration challenges and solutions. Civil society, including IDC, supported States in this process and advocated for them to take particular positions on various issues, such as immigration detention, alternatives to detention (ATD), and ending child immigration detention. The GCM is the official written result of these governmental exchanges and negotiations, and is the world’s first intergovernmental agreement covering all areas of international migration. While non-binding, the GCM provides governments with a UN policy framework for ensuring rights-based migration experiences across the world, more information here.

The GCM includes 23 Objectives which address a wide array of areas within the migration experience, such as regularisation pathways, access to services, discrimination issues, preventing loss of life, labour rights, human trafficking and many more. For IDC, Objective 13 aligns with our mission to reduce and end immigration detention: Use migration detention only as a measure of last resort and work towards alternatives (read the full text of Objective 13 on pages 20-21 of the GCM here.)

IDC was an integral civil society actor in the process of developing and ensuring that Objective 13 reflected existing human rights standards and obligations, and offered a solutions-focused way to action commitments. IDC and partners strategically negotiated and collaborated with different government actors to secure inclusion of particular provisions within Objective 13, including commitments to work towards the end of child immigration detention, to prioritise ATD, and to ensure a human rights-based approach to GCM implementation. While IDC and our partners had even stronger commitments that we wanted on these issues, the resulting Objective 13 in 2018 helped to set concrete milestones for our continuing advocacy towards ending immigration detention for all, particularly through holistic and collaborative whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches that centre impacted migrant communities and leaders with lived experience of detention.

The IMRF

Now, four years later, the UN General Assembly is convening the International Migration Review Forum (IMRF), which will formally review the progress of governments and stakeholders in implementing the commitments and principles stated in all of the GCM Objectives. This review will happen every four years, with the inaugural IMRF taking place from 17-20 May 2022 in New York City. Further, States have agreed that each IMRF will produce a Progress Declaration - an official document outlining efforts made towards enacting the GCM framework over the four-year period being reviewed, including suggestions for moving forward and improving progress.

For IDC, a key aim in the lead up to and during the first ever IMRF has been to influence the drafting of this Progress Declaration, particularly in relation to the implementation of Objective 13. To do this, we have been working in close collaboration with civil society partners, leaders with lived experience, UN agencies, governments, local authorities, and other stakeholders invested in this global process, including the State co-facilitators of the IMRF and the Progress Declaration negotiations, Luxembourg and Bangladesh. IDC and partners have been advocating to integrate the following key actions related to Objective 13 into the 2022 Progress Declaration:

- Uphold the GCM guiding principles and ensure there is no regression from the GCM adopted in 2018

- Acknowledge the steps taken by States, civil society actors, and other stakeholders to progress Objective 13 over the past 4 years

- Acknowledge the critical role of migrant communities and ensure full and meaningful participation and collaboration

- Include concrete and practical guidance to phase out immigration detention, and implement rights-based and community-centred ATD where applicable

- Solidify opportunities for peer-learning to enhance international cooperation, whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches

- Build on progress and strengthen the path towards ending child immigration detention that also leads the way to ending immigration detention for all

What happens during the 4 days of the IMRF?

The IMRF is a process led by States and convened by the UN General Assembly, therefore the agenda includes a set of plenaries geared towards facilitating exchange between States. An Interactive Multi-stakeholder Hearing for civil society and other stakeholders will take place on 16 May, as well as four thematic Roundtables on 17 and 18 May covering each of the 23 GCM Objectives. Anyone can view these roundtables, broadcasted here, while those registered and attending can join in person. IDC’s Executive Director Carolina Gottardo will moderate Roundtable 2, which includes Objective 13. Summaries of all four roundtable discussions are then shared in a policy plenary on 18 May, which will also showcase successes, challenges, and gaps in GCM implementation. Finally, on 20 May, the last day of the IMRF, the Progress Declaration will be adopted by Member States.

Further, civil society, UN agencies, governments, local authorities and other stakeholders will host side events during the IMRF to maximise momentum and engagement on various issues. In IDC’s role as co-lead of the UN Network on Migration Working Group on Alternatives to Detention alongside UNICEF and UNHCR, we are co-organising a side event with the governments of Thailand, Portugal, and Colombia. This 19 May panel event will focus on ending child immigration detention, and feature long-time IDC partner Hayat Akbari, a campaigner and advocate with lived experience of child detention, alongside government and UN representatives, and IDC’s Executive Director Carolina Gottardo who will provide insight into upcoming IDC research on detention and ATD. This is an online event, and we cordially invite those interested to join us here.

The UN Secretary General has also commenced a Pledging Initiative, which encourages States, UN agencies, civil society, and other stakeholders to pledge “a measurable commitment to advance the implementation of one or more GCM principles, objectives or actions.” Civil society can engage governments for pledges, which can be submitted here for presentation during the IMRF, and then used to support ongoing advocacy. IDC has been engaged in this initiative by supporting some governments with their pledging processes.

IDC’s Approach During the IMRF & Beyond

For IDC, the IMRF is a key milestone towards building momentum and furthering the global movement to end immigration detention. We do this through analysing the progress, gaps and challenges experienced by governments, civil society, communities, and other stakeholders in implementing Objective 13. Through reflection and taking stock, we identify promising developments, and agree on ways forward to strengthen and expand practices towards ending immigration detention.

To this end, IDC engaged in a series of research initiatives over the past few months, and will release three reports on immigration detention, ATD and Objective 13 implementation:

- Gaining Ground: Promising Practice to Reduce and End Immigration Detention - a global mapping that overviews promising ATD practices across the world

- Immigration Detention and ATD in the Asia Pacific Region - a UN Network on Migration collaboration providing insights on regional promising practice

- An IDC and UNICEF MENA collaborative mapping report identifying promising practice to end child immigration detention in the region

This strong and new evidence-base creates a catalyst for invigorating targeted peer-learning at regional and global levels, as well as exchange of technical expertise within and across regions, which will make IDC and our members and partners more impactful on the ground. Since its inception, IDC has prioritised the development of national, regional and global communities of practice that aim to change legal frameworks, policies and practice, and build more effective government and civil society partnerships through a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach. IDC’s new research provides cutting-edge knowledge that can be used to make collaborative change through concrete action. This strengthens existing communities of practice and peer learning exchanges, and ultimately supports governments in implementing Objective 13 by looking into promising developments and addressing challenges and gaps.

More broadly, the IMRF gives all of us in the migration sector an opportunity to shape the global narrative of civil society advocacy. We identify the wins and losses for ourselves, and ensure that communities affected by migration policies are provided with the opportunity to lead in advocacy that directly impacts their own lives. Global events such as these are best utilised when civil society engages to showcase and build our collective expertise across the world. In particular for IDC, the IMRF is a critical moment to connect local, national, regional and global advocacy, and ensure that grassroots expertise and leaders with lived experience of detention are centred at each and every level.

As the focus moving forward will be strongly placed on national implementation, including further promoting voluntary national reviews of implementation and the development of national action plans by governments, all of our roles in actualising the GCM are most important beyond the 2022 IMRF. Civil society must be ready to organise, engage, and advocate to ensure governments are living up to their GCM commitments on the ground. While the IMRF is an opportunity to reflect and take stock, it is also an opportunity to envision and plan for strengthening and scaling up progress in the years to come, and ensure that real impact on the lives of migrant communities is at the centre of our changemaking.

For continued updates on the IMRF, please subscribe to the UN Network on Migration newsletter here, and view live streaming coverage of the IMRF in UN official languages at the UN TV website here. Please also contact IDC Global Advocacy Coordinator Silvia Gomez [email protected] for more information.

Written by Carolina Gottardo Executive Director, Silvia Gómez Global Advocacy Coordinator & Mia-lia Boua Kiernan Communications & Engagement Coordinator

Joint Statement on Immigration Detention Policies & Practices in Malaysia

Published on Monday 2 May, 2022

International Human Rights Community Urges Malaysian Government to Rethink Immigration Detention Policies & Practices

In the early hours of 20th April, over 500 Rohingya refugees, including 97 women, 294 men, and 137 children, escaped from a detention centre in Sungai Bakap. It was later confirmed that 7 of those who fled were killed tragically in a traffic accident, including three young children. Over the following days, at least 467 people were re-detained, and there is a continuing effort by government authorities to find and arrest the remaining refugees who fled. As members of the international human rights community, we the undersigned are deeply concerned by this heartbreaking loss of life, and we urge the Malaysian government to conduct an immediate, thorough, and independent inquiry into the underlying circumstances and detention conditions which led to such severe levels of human desperation, and prompted an escape attempt by so many.

It is reported that a large number of Rohingya refugees are held indefinitely in immigration detention centres in Malaysia, without possibility of release. This has been compounded by the Malaysian government refusing UNHCR access to detention centres in order to conduct refugee status determination processes since August 2019. Home Minister Hamzah Zainudin has stated that refugees held at the Sungai Bakap detention centre have been detained for over two years and cannot be deported.

The deprivation of liberty of people and families seeking safety and asylum is a serious concern to us, and is a fundamental violation of human rights. The impact of detention on mental, physical, and emotional health has been extensively researched and consistently shows that people, especially those who have previously experienced traumatic events, face high levels of mental health challenges as a result of being detained. Further, ample evidence proves that the severity of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress that a person experiences is closely linked to the length of time they have spent in immigration detention.

As of 26 April 2022, the Malaysian Immigration Director-General Datuk Seri Khairul Dzaimee Daud reported that there were 17, 634 migrants in immigration detention centres nationwide, including 1, 528 children. The Home Ministry has also further reported 208 recorded deaths in immigration detention between 2018 and February 15th 2022, citing Covid-19, septic shock, tuberculosis, severe pneumonia, organ failure, lung infection, heart complications, dengue, diabetes, and breathing difficulties, among others.

We strongly urge the Government of Malaysia to:

- Carry out a comprehensive review of the current policies and practices of immigration detention centres in Malaysia to ensure they are in line with international legal standards

- Ensure full transparency of the investigation and review, and make the process and results available and accessible to the public

- Proceed with immediate implementation of the ATD pilot officially launched in February 2022, and ensure Rohingya children are included within the scope of the pilot

- Simultaneously, take immediate steps to enact legal and policy changes to ensure that children are no longer detained for migration-related reasons, given that only 5 children are to be released at any time under the ATD Pilot

- Follow through on the pledges made to uphold human rights, in order to secure their seat on the United Nations Human Rights Council, for example, “to implement policies and legislations that promote and protect the rights of the most vulnerable communities,” which indisputably include refugees, people seeking asylum and stateless persons, especially women and children

- Immediately release all persons registered with UNHCR from immigration detention and grant UNHCR access to all immigration detention centres to continue registration of persons of concern

- Grant access to Doctors Without Borders Malaysia, and other NGOs to immigration detention centres to ensure detainees have access to medical treatment and support services

Malaysia continually lags behind its closest neighbours in ASEAN, specifically Thailand and Indonesia, who have released hundreds of children from immigration detention into community-based care since 2018. Further, in Indonesia, the local government in Aceh has set up a task force to manage emergency response. These processes link refugee communities to support from IOM, UNHCR, Geutanyoe Foundation, JRS Indonesia, and other organisations, until the national government advises which cities they will be transferred to for sustainable and ongoing accommodation and support.

We call upon the Government of Malaysia to respond to this human tragedy with compassionate leadership and integrity, and commit to protecting the rights of refugees and people seeking asylum in Malaysia, as committed to in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and the ASEAN Declaration on the Rights of Children in the Context of Migration. The Government of Malaysia must reconsider its current policies and systems of immigration detention, which are arbitrary, harmful, costly and ineffective. Instead, they should develop and implement non-custodial alternatives to detention, particularly for people in vulnerable situations, such as children, ethnic and religious minorities, women, gender-diverse and LGBTI+ people.

It is time for Malaysia to step up to its international commitments, and we stand prepared to support the Government and other civil society organisations in developing systems and frameworks for alternatives to detention, and ensuring that nothing like this ever happens again.

Signed,

International Detention Coalition

Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network

ASEAN Parliamentarian on Human Rights

Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (Forum-Asia)

It’s Been 3 Years Since the Signing of the ATD-MOU in Thailand: Where Are We Now?

On 21 January 2019, representatives of 7 Thai Government agencies signed the Memorandum of Understanding on the Determination of Measures and Approaches Alternatives to Detention of Children in Immigration Detention Centres (ATD-MOU), as well as Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) to implement the ATD-MOU starting in September 2020. The ATD-MOU was a concrete outcome of a pledge made by Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha during the 2016 Leaders’ Summit on Refugees at the United Nations in New York. At the summit, he publicly pledged to end the immigration detention of refugee and asylum seeker children in Thailand.

Ever since the ATD-MOU was signed 3 years ago, IDC and HOST International have worked in partnership to collate and strengthen the evidence-base that can be used to increase practical understanding of community-based, rights-based, and gender-responsive ATD within the Thai urban refugee context. IDC and HOST have also been working together, and with various local partners, to strengthen ATD policy and practice in Thailand during this time.

To mark the 3rd anniversary of the ATD-MOU, IDC, HOST International and the Embassy of Canada to Thailand organised an event: “Strengthening Community-based ATD in Thailand: Lessons Learned From the Past 3 Years.” This event was funded by the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI) and was held at the Novotel Sukhumvit Bangkok on 28 February 2022.

Over 60 people attended from a diverse group of stakeholders, including government agencies, civil society organisations, UN agencies, and diplomatic missions. Attendees came together to share and discuss the growing evidence-base, as well as critical pathways to shift focus from enforcement-focused models of ATD, towards ATD that is centred on community-based protection and care for all children and their families. The event began with opening remarks by Her Excellency. Dr. Sarah Taylor, the Ambassador of the Embassy of Canada to Thailand. She called on everyone to consider the crisis in Ukraine, and the stark reminder it gives us all that refugees and people seeking asylum flee their countries by no fault of their own, and security risk must be carefully assessed, not assumed. Dr. Taylor affirmed that the detention of people seeking asylum must only be used as an absolute last resort, and the detention of children is never justified.

These important remarks were followed by Laddawan Tantivithayapitak, President of HOST International Foundation Thailand, who emphasised HOST International’s mission to make life better for people on the move in Thailand by fostering humanity, hope, and dignity for all. Tantivithayapitak reflected on the partnership between HOST International and the Department of Children and Youth (DCY), as well as other key stakeholders who have supported children and their families being released from immigration detention since 2018, through a community-based Case Management programme.

Yuhanee Jekha, Regional Programme Manager at HOST International, then presented the independent evaluation report of HOST’s community-based Case Management programme conducted in 2021. This report highlighted the programme’s successes, lessons learned, and recommendations for specific interventions to bring more humanity and dignity to the urban refugee experience in Thailand. For example, following release from detention many children and their families found it very difficult to navigate complex legal systems, to meet basic daily needs, to access and pay for health care, manage finances, and participate in education. To address these issues, community-based Case Management in urban areas has proven to work extremely well and has excellent potential to grow to scale. In Thailand, this approach is cost-effective, supports compliance with immigration requirements, and leads to improved well-being by providing holistic and tailored support. This approach also requires strong partnership, the ongoing involvement of local communities, and long-term investment to support strengthened migration governance outcomes in Thailand. For more information about this evaluation, please contact HOST International.

The event also featured a panel, which included Suthida Srimongkol, Director of Protection System Development Sub-Division at the Department of Children and Youth (DCY), Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, and Pasatree Comwong, Senior Social worker at Save the Children Thailand. The panel discussion was moderated by Parinya Boonridrerthaikul, Child Protection Officer at UNICEF Thailand.

Srimongkol shared an overview of the child protection system being implemented at the sub-district level by DCY since 2017, and discussed the localisation of child protection such as the Sub-district Child Protection System (SD-CPS), the Child Maltreatment Surveillance Tool (CMST), and the Child Protection Information System (CPIS). She underlined that case management is key to both short-term and long-term protection of children, as an effective case manager plays a vital role for children and families who are rebuilding their lives in the community. DCY also works at the district and provincial levels to build the capacity of local authorities and equip them with the skills and tools needed to work with children. Srimongkol welcomed civil society to partner with DCY in these efforts to strengthen child protection mechanisms within local communities.

Comwong emphasised the role of community in the protection of vulnerable children and indicated that it is critical to understand the community’s capacities and perform resource mapping. Through these mapping processes, the community is able to recognise the different roles they can play to protect vulnerable children. Further, these community and resource assessments need to be accessible and updated routinely. Boonridrerthaikul added that it is important to stay focused on the big picture, which is not just about non-detention, but about enabling access to legal status, health care, education, and meeting other important needs of children.

Angkhana Neelaphaijit, President at Justice for Peace Foundation and former Commissioner of the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand also delivered key remarks. She clarified that while Thailand might regard itself as a transit country, many people cannot ever be repatriated or resettled elsewhere. Therefore, under current Thai policies many are forced to spend much of their lives in immigration detention, some for over a decade. This presents a moral challenge to Thailand’s commitment to human rights. Neelaphaijit shared key recommendations to the Thai government and Thai people in moving forward:

- Ensure that all children receive proper care and protection without discrimination on any grounds, and with consideration of the best interests of the child.

- Accelerate the finalisation of the regulation and procedures of the national screening mechanisms, so that refugees and people seeking asylum can work and be independent.

- Cultivate accurate information and inform public understanding about the root causes of migration, and the right and need for people to be able to seek international protection and a better life.

- In cases of enforced disappearance, sexual abuse, and human trafficking, the government and relevant agencies must accelerate investigations and bring the perpetrators to justice, while also providing support and remedies to victims and survivors.

- Laws must be changed to centre the experiences of survivors, including the Immigration Act, the Anti-trafficking In Persons Act.

As IDC Southeast Asia Programme Manager and a long-time Thai advocate, I also had a chance to speak at this important event and share IDC’s newly published research analysis of the Promising Practices in ATD for children and their families. As someone who has been part of the ATD-MOU’s development from day 1, I have witnessed Thailand make significant progress since the ATD-MOU came into effect in 2019. Hundreds of children and their families have been released from immigration detention over the last three years. However, children continue to be subject to immigration detention in Thailand, as the ATD-MOU is only triggered once a child has been arrested and detained. Children may be released with their mothers, though mothers are required to pay bail at prohibitively high costs. Fathers are not typically considered for release under the ATD-MOU, which results in family separation and pressure on mothers who find themselves as single heads of household. Through IDC’s research analysis, we aim to support the Thai government and stakeholders by illustrating what rights-based ATD for children and their families looks like, alongside promising examples from different country contexts that may be of particular interest.

Political will, commitment to the best interest of the child, and multi-stakeholder collaboration have been the key drivers of advocacy efforts among Thai civil society, government partners, UN agencies, the diplomat community, academics, and people whose lives are impacted by immigration detention. For me, the 3rd anniversary of the ATD-MOU is a vital milestone for all stakeholders to consider how to improve ATD policy and practices in Thailand to ensure that all children and their families affected by immigration detention can access community-based, rights-based, and gender-responsive ATD. With Thailand’s global leadership on ATD, I believe that one day immigration detention will no longer exist in my country, and people who migrate here will live with rights and dignity - which is IDC’s vision for the world.

IDC shares much gratitude to HOST International, the Embassy of Canada to Thailand, the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI), and our other local members and partners for your continued collaboration and commitment.

Written by Chawaratt Chawarangkul IDC Southeast Asia Programme Manager & Photo Credits to the Embassy of Canada to Thailand

An Exploration of Accommodation Provision for Migrants in the EU

This blog is written by Rositsa Atanasova, Advocacy Expert at the Center for Legal Aid – Voice in Bulgaria, a European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN) member and ATD pilot implementer, and overviews the results of an EU mapping which demonstrates a wide variety of options when it comes to accommodation provision for migrants, including those that could be used within designated ATD initiatives.

In many national contexts the application of alternatives to detention (ATD) remains limited in practice, because detention is applied by default to foreign nationals who have lost the right of residence, and not as a measure of last resort. According to EU and international law, states must consider ATD before depriving people of their liberty. Yet too often we see an improper reversal of the burden of proof, whereby it is up to people in irregular situations to contest the presumption of detention by proving that they fulfil the requirements for the application of alternatives.

In Bulgaria, the experience of the Centre for Legal Aid – Voice in Bulgaria (CLA) is that there is almost no individualised assessment of the principles of necessity, reasonableness and proportionality, as required by European and international legal standards. Instead, authorities are only willing to consider ATD when an individual has met the conditions in the law for the implementation of alternatives through case management support. Frequently, this includes a requirement that suitable accommodation be available.

In order to better understand current accommodation options in the EU and Bulgaria, as well as their potential for expansion in the context of ATD, in late 2021 I carried out a study on options for irregular migrants. Here, I explain my conclusions as well as the implications when it comes to ATD for people in immigration detention.

Accommodation Options for Irregular Migrants in the EU

The study of accommodation options for irregular migrants, which I conducted for CLA with the support of our donor EPIM, consists of a mapping paper and an advocacy strategy. The mapping paper systematises current practice in the EU and advances a new conceptual framework for analysis of the link between ATD and accommodation. It is based on desk research and fills a gap in recent research on the accommodation of irregular migrants in the EU. The advocacy document, in turn, explores current practice in Bulgaria and contains an action plan for the short and mid-term in order to improve access to accommodation and expand the use of ATD. It draws on meetings with a range of stakeholders including government agencies and local authorities, NGOs, service providers and beneficiaries. The interviews provided information about the range of existing services, which was not available through desk research alone.

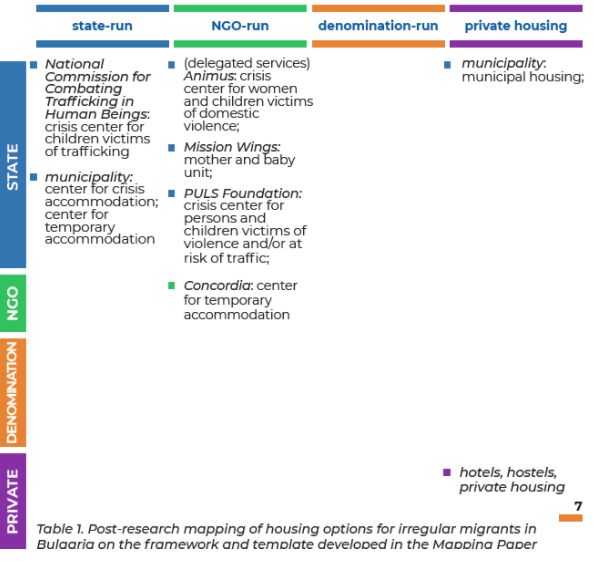

The range of accommodation options for irregular migrants in the European context can be mapped on a matrix (Table 1) in relation to the nature of the service provider and the nature of any potential partner. The axes represent a spectrum of accommodation provision, from state-run housing to private accommodation through NGO and denomination-run residential options. Such a model allows us to visualize dependency on an intermediary to access accommodation alternatives and how much of that service-provision is dominated by the state. In addition, the chart illustrates potential new areas for service-creation that might not yet exist. The matrix is ultimately also an instrument for measuring whether responses are mostly community-based or institutional.

As illustrated by the examples above, accommodation for irregular migrants in the EU, if available at all, tends to be institutional and oriented towards return. In exceptional circumstances, people who cannot be deported to their country of origin can be accommodated in open reception centres for asylum-seekers or in homeless shelters. These options, however, are not presented as possible ATD, but as a way for authorities to provide a bare minimum of material assistance. The different housing possibilities presented here are most often used by irregular migrants who are not in contact with the authorities. Such pathways, however, can be quickly and usefully deployed to offer alternatives to detention in an emergency situation, as illustrated by regularisation initiatives during the pandemic. This is why it is useful to consider the full range of available choices in an effort to expand the ATD portfolio.

Accommodation Options for Irregular Migrants in Bulgaria

The study of accommodation options for irregular migrants in Bulgaria reveals a gradually shrinking space, however. Access to state services, State Agency for Refugees (SAR) reception centers and municipal housing have become more difficult to access even for beneficiaries of international protection, not to mention those in an irregular situation. Service providers are less willing to bend the rules to accommodate people without documents in crisis, particularly in light of pandemic measures. Mothers with children and victims of domestic violence or trafficking are the only groups that face fewer impediments, but even their access frequently involves protracted negotiations with service providers and social workers to renew referrals on a case by case basis. Placement in a service, ultimately, does not qualify as a formal ATD, but amounts to tolerated stay that is not formalized in any way.

Private housing remains the most readily available option for irregular migrants and the only one that currently qualifies as a formal ATD. The advantage of the Bulgarian system is that those who lend property to people without documents do not seem to incur criminal or administrative sanctions, in line with FRA recommendations. As a downside, private arrangements are onerous due to the need to find a guarantor who is willing to provide financial support, as well as to locate suitable accommodation amidst exploitative renting schemes, discrimination and limited choices.

Implications for ATD

The results of the mapping and advocacy strategy, outlined above, demonstrate a wide variety of options when it comes to accommodation provision for migrants, including those that could be used within designated ATD initiatives. On the face of it, the Bulgarian accommodation requirement mentioned above could potentially be good news because it opens up the space for NGOs to develop accommodation options and case management programs for irregular migrants in order to expand the use of ATD for those at risk of immigration detention. Moreover, we know how essential stable and appropriate accommodation is for those going through migration processes; the government requirement could be seen as a recognition of this. By drawing on lessons learned across the EU, and developing additional accommodation models, the implication is that advocates for the rights and liberties of migrants can encourage a shift on the part of governments to using ATD.

The reality, however, is more complex. Given the standing presumption of detention in Bulgaria, it is not clear whether the availability of more housing options for irregular migrants will necessarily lead to greater application of alternatives. Instead, it seems that the accommodation requirement is being used as an excuse to justify the government’s failure to systematically consider ATD, linked to a general political resistance to community-based solutions (including on national security grounds).

CLA practice indicates that authorities tolerate stay in services when it will spare them the responsibility for vulnerable individuals and are more willing to apply ATD when presented with ready-made solutions. The implication, therefore, is that whilst accommodation remains a key part of ATD programmes, the provision of more accommodation options alone is unlikely to be the catalyst for change that it might seem at first glance to be. Provision of accommodation, whilst a key part of ATD, is certainly not a silver bullet. Instead, the reversal of the ATD logic – which sees detention as the primary precautionary measure, as opposed to a measure of last resort – should be challenged on its own terms. In particular, it is essential that the burden of proof is turned back around so that presumption of liberty, rather than detention, becomes the norm. In Bulgaria, possible routes lie in advocating for access to services on the basis of the new Law on Social Services, which is theoretically applicable to all persons within the jurisdiction, and NGOs stepping in as mediators, guarantors or service providers for irregular migrants.

IDC is a co-coordinator of the European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN), and this blog was originally posted on the EATDN site here. Find out more about the work of Centre for Legal Aid – Voice in Bulgaria, including their pilot ATD programme here.

The Action Access Alternative to Detention Pilot: Evaluation of Community-Based Support

An independent evaluation of the pioneering pilot project delivered by European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN) member Action Foundation and funded by the UK Home Office has found it is more humane and significantly less expensive to support women in vulnerable situations in the community as an alternative to keeping them in detention centres. In this blog, Action Foundation Chief Executive Duncan McAuley summarises the pilot, its aims, and the findings of the evaluation.

In 2018, the UK Government published the Shaw Progress Report, a follow-up to the Review into the Welfare in Detention of Vulnerable Persons produced by Stephen Shaw, former Prisons and Probations Ombudsperson for England and Wales. Amongst other recommendations, the progress review urged the UK Government to “demonstrate much greater energy in its consideration of alternatives to detention.” Shortly after its publication, the Government announced the creation of a Community Engagement pilot (CEP) Series, which set out to test approaches to supporting people to resolve their immigration cases in the community.

Action Access: a civil society-government partnership

Following a successful bid process, Action Foundation – which had played a key role in the advocacy efforts that led to the introduction of the CEP – was granted the contract for the first of the four pilots, and our Alternative to Detention (ATD) project was born. The Action Access pilot ran between 2019 and 2021 and supported 20 women seeking asylum in a community setting in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in the North East of England. With one exception, prior to joining the pilot all of the women had been detained in Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre.

Upon joining the pilot, the women were provided with shared accommodation, received one-to-one support from Action Foundation staff, and were supported to access legal counselling. Although it wasn’t a requirement of the pilot, the women also benefited from Action Foundation’s broader program of activity such as its free English language classes and weekly community gatherings, facilitating socialisation, signposting and referrals.

The pilot was framed around five pillars of support:

- Personal stability: achieving a position of stability (in relation to, for example, housing, subsistence and safety) from which people are able to make difficult, life-changing decisions;

- Reliable information: providing and ensuring access to accurate, comprehensive, personally relevant information on UK immigration and asylum law;

- Community support: providing and ensuring access to consistent pastoral and community support, addressing the need to be heard and the need to discuss their situation with independent and familiar people;

- Active engagement: giving people an opportunity to engage with immigration services and ensuring that they feel able to connect and engage at the right level, enabling greater awareness of their immigration status, upcoming events and deadlines with routine personal contact fostering compliance; and

- Prepared futures: being able to plan for the future, finding positive ways forward, developing skills in line with their immigration objectives, identifying opportunities to advance ambitions. Through this approach, the pilot hopes to provide more efficient, humane and cost-effective case resolution for migrants and asylum seekers, by supporting migrants to make appropriate personal immigration decisions.

The model was innovative in a number of ways. The combination of a holistic approach to case management with comprehensive legal support, for instance, was integral to the delivery of the pilot and seen to make case resolution more likely. In addition, although there have been other examples of ATD in the UK, including an ongoing project run by Detention Action, Action Access was the first time that such a pilot had been built from a formal civil society-government partnership. The relationship between many parts of the Home Office and civil society are often tense, and the pilot represented a leap of faith. But we found the experience of working with the Home Office Community Engagement Team a really positive and productive one. There was a genuine collaborative relationship between the Home Office, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and Action Foundation and this unique partnership demonstrates a model of working that is both dynamic and effective. Importantly, it demonstrates the success possible if the Home Office is willing to replicate this approach in the future.

Evaluating the pilot’s success: Improved wellbeing and reduced costs

The findings of the pilot were officially published in late January by UNHCR, who had commissioned the evaluation. The report, entitled Evaluation of the Action Access Pilot, was researched and compiled by Britain’s largest independent social research organisation, the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen). Commenting on the effectiveness of the pilot, NatCen’s report states:

“Our evaluation found qualitative evidence that participants experienced more stability and better health and wellbeing outcomes whilst being supported by Action Access in the community than they had received while in detention. Evidence from this pilot suggests that these outcomes were achievable without decreasing compliance with the immigration system.”

The evaluation said this provided “a more humane and less stressful environment for pilot participants to engage in the legal review and make decisions about their future, compared with immigration detention. Even when those decisions were difficult and participants had no legal case to remain in the UK, the pilot gave the participants space and time to engage with their immigration options.”

The more humane environment was a repeated theme shared with researchers, with one of the participants saying, “In detention, you don’t have this kind of positive atmosphere. You just want to cry. You just want to stop eating. You just want to kill yourself. This is because you are so in trouble there, right. Then, when you come out, it’s like everything is going to be nice again… the atmosphere is very different, and I think you recover yourself.”

The evaluation of Action Access also suggests that keeping people in the community is much less expensive than holding an individual in detention. The report states that the potential savings could be less than half the cost of detention, in line with Action Foundation’s own calculations.

Next steps: Introducing ATD as ‘business as usual’?

While Action Access may have come to an end, Action Foundation continues to work according to the same model: combining one-to-one case management with comprehensive legal advice in order to ensure that people are able to resolve their cases in the community. We continue to believe that this type of community-based support is the best way of supporting people going through the migration system and can be used effectively instead of detention.

As for the UK Government’s next steps, it remains to be seen what will come of the CEP Series in practice. A second pilot is already underway, run by the King’s Arms Project, however there have been no confirmations that the CEP series will continue beyond this.

The seven recommendations made in the Action Access evaluation, all of which the Home Office has accepted, included a call for them to “accelerate the introduction of effective aspects of the ATD programme into the Home Office’s ‘business as usual’ model.” We hope to see progress on this, and the upcoming International Migration Review Forum (IMRF) could be the perfect context to pledge to take action. In the UK as is the case elsewhere, there’s a growing need for a change of direction and a rethinking of the approach to migration management – particularly when it comes to immigration detention. We hope our pilot, and the evidence that has emerged from it, can contribute to those necessary changes.

IDC is a co-coordinator of the European Alternatives to Detention Network (EATDN), and this blog was originally posted on the EATDN site here. Also find out more about the Action Access pilot here and here.

IDC & ECDN Welcomes Launch of ATD Pilot in Malaysia

25th February 2022, Kuala Lumpur – The End Child Detention Network Malaysia (ECDN) welcomes the launch of the Alternative to Detention (ATD) pilot programme by the Malaysian Government. The pilot programme is anchored by the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development and the Ministry of Home Affairs. The pilot programme, which will provide temporary shelter for unaccompanied and separated children under detention, acknowledges the serious harms that children face in immigration detention and focuses on prioritising the physical and mental health development of children.

The ATD pilot programme is a step in the right direction towards fulfilling Malaysia’s obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which the nation ratified in 1995, and is timely, as Malaysia prepares to submit a status report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child. The standard operating procedure (SOP) framework for the ATD pilot, which was developed in consultation with select non-governmental organisations, is strongly guided by the principle of best interests of the child (Article 3), and further upholds the rights of a child to be protected from all forms of violence (Article 19), and to access special protection in the event of separation from family environment (Article 20). Further to that, the launch of the ATD pilot also works towards the implementation of policies and legislations that promote and protect the rights of the most vulnerable communities - which was one of Malaysia’s pledges made to secure their seat on the United Nations Human Rights Council, and signals Malaysia’s commitment to the ASEAN Declaration on the Rights of Children in the Context of Migration and its corresponding Regional Plan.

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has provided authoritative guidance that immigration detention is a violation of child rights, and as of October 11, 2021, the Home Ministry reported about 1, 425 children in detention centres nationwide. Malaysia has been lagging behind our closest neighbours in ASEAN, specifically Thailand and Indonesia, who have since 2019 released hundreds of children from immigration detention into community-based care. Thus, we welcome the launch of the ATD pilot programme as a step towards ending child detention in Malaysia, and we urge the Malaysian government to follow through in ensuring that all human rights of a child, and a child’s wellbeing and best interests are foregrounded and upheld throughout the process of release, community placement, as well as in our immigration policies. As we move forward, we strongly recommend to the Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development and Ministry of Home Affairs to develop a clear framework for monitoring and evaluation of the ATD pilot that focuses on the best interest of the child. We also call on the Malaysian government to provide further details and regular updates on the implementation of this ATD Pilot in Parliament.

We look forward to continuing working with the government, policymakers, and implementing staff to protect and uphold the human rights of all children in Malaysia.

About the End Child Detention Network (ECDN) The End Child Detention Network is a coalition of civil society organisations and individuals working to ensure that no child is detained in Malaysia due to their immigration status.

For more information, please contact: End Child Detention Network Coordinator - [email protected]

Growing Through The Azalea Initiative: Refugee Leadership Programme in Malaysia

In January 2022, the Akar Umbi Development Society, sister organisation of SUKA Society, an IDC member, launched the first series of workshops of the Azalea Initiative. The initiative is a women’s leadership development programme that aims to empower women of marginalised identities and increase their capacities to become changemakers within their communities. The aspiration is for them to become advocates in their own right, and catalyse change towards alternatives to detention (ATD) and an end to immigration detention.

In collaboration with IDC and IDC partners in Malaysia, and with close reference to IDC’s Community Leadership Curriculum, Akar Umbi has developed their pilot programme with modules surrounding themes of migration, identities, power, resilience, justice, solidarity and community organising. IDC’s Community Leadership Curriculum was developed with the goal of supporting the leadership and meaningful participation of people who have experienced or have been at risk of immigration detention. This is grounded in our belief that people with lived experience of detention must be involved in shaping the policies that directly impact their own lives and communities.

The first series of workshops of the Azalea Initiative was joined by 12 participants, who began their journey of learning how to plan, lead and implement projects with Akar Umbi’s support. A participant of the Azalea initiative reflected, "I now feel I can go outside to work if I wanted to. Before this, I felt that I could only stay at home and be a home-maker," demonstrating the significance of an initiative like this in changing lives, even in its initial stages.

For more information on the Azalea Initiative, visit Akar Umbi Development Society’s website and Instagram. For more information about IDC’s Community Leadership Curriculum, please contact IDC Communications & Engagement Coordinator, Mia-lia Boua Kiernan at [email protected]

Written by Hannah Jambunathan Community & Engagement Organiser - Malaysia

Hope in Efforts to End Detention of People Seeking Asylum in Mexico

People seeking asylum who apply for refugee recognition in Mexico while in immigration detention are required to remain in detention for the duration of their refugee status recognition process. However, should a person apply for asylum outside of detention, they will not be detained during their refugee status recognition process, given two conditions: first, that they remain in the federal entity (state) in which they are processing their application, and second, that they appear weekly before the corresponding authority to sign and declare their agreement to continue the process until a resolution is obtained.

Over the past decade, IDC and various organisations, such as Asylum Access México and networks such as Grupo Articulador México del Plan de Acción Brasil (GAM-PAB) and Grupo de Trabajo de Política Migratoria (GTPM), have promoted collective advocacy actions, initiatives and pilot programs for children to promote alternatives to detention (ATD).

On the basis of this and mindful of the severe injustice and harms endured in detention by people seeking asylum, in mid-2021, a civil society Advocacy Task Force against Detention was created to specifically advocate for an end to immigration detention of asylum seekers in Mexico.

The Task Force has focused on two activities: first, a campaign regarding the effects of detention on refugees and the need to eliminate detention for asylum seekers, aimed at raising awareness and promoting the prevention and elimination of detention in Mexico. Second, a proposal to reform several regulations in order to end this practice.

While the program allowing for the release of asylum seekers from detention has been implemented in the country since 2016 by the National Institute of Immigration (INM), the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR), and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (ACNUR), it remains an informal and discretionary practice without clear and public criteria, and at the end of 2020 it became subject to additional limitations. It is thus questionable whether the program can be considered an ATD.

All people seeking asylum are therefore at risk of detention at present. Children are an exception to this as their detention was prohibited, although not totally eradicated, by reforms in the Migration Law and the Law on Refugees, Complementary Protection and Political Asylum in 2020.

The legislative reform proposed by the Advocacy Task Force against Detention is ambitious, ranging from additions to the Constitution, to modifications of the Migration Law and the Law on Refugees, Complementary Protection and Political Asylum, among other initiatives. It aims to guarantee that asylum seekers are not subject to detention.

In 2022, the Advocacy Task Force aims to continue to raise awareness and advocate for the above-mentioned reforms. In addition, a series of actions are planned to promote the adoption of ATD for asylum seekers in both policy and practice, as well as to influence judicial decisions that will prevent detention and guarantee access to due process.

Written by Diana Martinez Americas Program Officer, Carolina Carreño Americas Childhood Project Officer & Elizabeth Alvares Americas Programme Assistant

Uncertain Future for Mexico's Asylum Seeker Release Program

The lack of clarity surrounding Mexico's asylum seeker release program (programa de salidas de la estación migratoria, SEM), together with the absence of public policy guaranteeing the rights of refugees, present significant obstacles for asylum seekers in refugee recognition procedures before the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR).

Migration authorities persist in increasingly and automatically detaining migrants and asylum seekers. In 2021, 307,679 people were detained, up from the 82,379 people detained in 2020, despite the pressure exerted by civil society organisations in the face of the national health emergency issued on 30 March 2020 by the federal government due to SARS-COVID-19. This pressure took the form of legal actions and advocacy to free vulnerable migrants and asylum seekers held in detention centres. During 2020, detentions continued and few asylum seekers had access to the SEM program. While the program was initially viewed as promising and as a positive practice, as access for detained asylum seekers became more restricted, it gradually dissipated and effectively came to an end,

The SEM is a tripartite mechanism between the National Institute of Immigration (INM), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (ACNUR), and the COMAR. It was first implemented in July 2016, with the aim of providing alternatives to detention for asylum seekers in detention centres.

The SEM benefitted 18,064 people between January 2017 and October 2020. However, in November and December 2020, only 145 people were able to access the program following new guidelines by the National Institute of Immigration (INM) to all detention center authorities. These instructions excluded people from the program if they had entered Mexican territory irregularly; if they were traveling alone, that is, without accompanying family, and had entered irregularly; or children who had entered irregularly. This evidently violates both Mexican law and international conventions that establish the international principle of not sanctioning asylum seekers for irregular entry.

New research on alternatives to detention for refugees in Mexico

In 2020, Asylum Access Mexico published a report on their research into the challenges and obstacles faced by asylum seekers in accessing the SEM program, as well as the process of applying for refugee status from detention. This research found that detention is in itself an obstacle to applying for refugee status in Mexico. In addition, those who applied for asylum when in detention, were forced to remain detained for an average of 40 days. In one case, a person was detained twice. They were initially held for a little over 40 days, followed by a further 2 months when detained in another city, even though they had been released from the original detention center under the SEM program.

The SEM also lacks clear criteria and transparency. As the program is neither institutionalised nor regulated, it is subject to discretion in its implementation and practically depends on the decision of the public official on duty. This discourages effective access to asylum. Ambiguity around how the program operates creates uncertainty for refugees. As such, many opt not to apply for asylum while in detention, as they understand that this will entail being held for prolonged periods. In this regard, people prefer to accept their deportation, despite the risk posed by being returned to the country from which they fled in the first place in order to safeguard their lives.

These findings reflect the urgent need to reform the refugee and immigration laws in Mexico in order to guarantee that immigration detention for people requiring international protection ceases to be an automatic and arbitrary practice, and is used only as a last resort in exceptional cases, with strict compliance to the criteria of necessity, proportionality and reasonableness of such detention.

By Alejandra Macías Delgadillo, Executive Director, Asylum Access Mexico & IDC International Advisory Committee Member

Updates from IDC’s MENA Regional Programme

In December 2021, we launched an IDC Facebook Page for the MENA Region! This page will include regular updates in Arabic and English, and will also coordinate a private Facebook group for IDC MENA members to enhance ongoing engagement between our members and strengthen communication and collaboration.

Most recently in February 2022, IDC announced a new online training that we are co-organising with UNICEF on 17 March. This training will focus on supporting civil society groups and initiatives to enhance their capacity and build a network of actors working on issues related to ending the immigration detention of children in the MENA region.

IDC and UNICEF Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are carrying out research on the current state of immigration detention and the related legislations and practices in the MENA region, especially concerning children. In addition to identifying opportunities for the implementation of community-based Alternatives to Detention (ATD). The purpose of this research is to inform the International Migration Review Forum in May 2022, which serves as the primary intergovernmental global platform to discuss and share progress on the implementation of all aspects of the Global Compact for Migration.

Refugee protests and online mobilisation

In January, 600 refugees and migrants in Tripoli, Libya, were arrested and detained after protesting for months in front of a UNHCR building. They were demanding safety and protection, as well as seeking resettlement out of the country. Read more about these developments in our blog post: What’s happening in Tripoli? in English and Arabic.

Issues in Libya are similar to previous refugee protests in Egypt in 2020, where refugees in front of a UNHCR building were demanding justice following the killing of a refugee child. The protesters, who were mostly Sudanese, were detained by authorities. More recently in February 2022, refugees in Tunisia have also started protesting and demanding necessary protection assistance, including resettlement to Europe.

These examples reflect the growing need for proper mechanisms to listen and understand the concerns and challenges of refugees and migrants, and consider what is needed beyond the current systems in place. Additionally, migrant and refugee communities have started using social media to reach wider audiences internationally, using hashtags such as #EVACUATErefugeesTUNISIA4yearsisENOUGH and #EvacuateRefugeesFromLibya. Impacted communities are taking these actions to raise their voices and be heard, and to appeal to activists, organisations, and social movements beyond the borders of the countries where they feel trapped inside. Furthermore, refugee-led initiatives are increasing in the region to cover gaps in daily assistance, such as this online fundraising campaign initiated by refugee communities in Libya (GoFundMe) to support refugees and migrants with basic needs. The goal is to raise 15k euros, and they are already two thirds of the way there!

Agreements to prevent migrant arrivals in Europe continue

In Libya, despite the grave human rights violations reported inside Libyan detention centres, there are currently 12,000 migrants and refugees in immigration detention. Italy, with backing from the EU, is continuing its 5-year long agreement with Libya. Signed in 2017, this agreement provides support to Libyan Coast Guards, allowing them to intercept and return migrants crossing the Mediterranean to Europe. Despite continuation of the agreement, the UN maintains its call for a total suspension of such agreements, declaring that “Libya is not a safe port of disembarkation for refugees and migrants.”

In countries like Tunisia, agreements with European countries have not been made public. However, some organizations have raised concerns over proposals for further collaboration between Tunisia and some European states, given increased migration from the country in the last few years. So far, 5,000 Tunisians have been repatriated from Italy.

Restrictions such as these have left people on the move with limited options to seek international protection, and better economic opportunities to provide safety, stability and wellbeing for their loved ones and families. These difficult predicaments have led migrant communities to speak out about their conditions, as described above. Additionally, in January 2022, two Nigerian migrants brought a case against Italy and Libya before the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Their case states that Italy and Libya failed to adhere to their international obligation to protect women’s rights with regards to the complainants, who are also victims of human trafficking. Updates on this case are said to be forthcoming in the next few months.

Deportations, repatriations and returns

In Egypt, detained unregistered people seeking asylum have limited access to UNHCR, asylum procedures or legal assistance. Human Rights Watch reported in 2021 about the poor conditions of nine Eritrean asylum seekers who were detained, including children. By the end of 2021, Egypt had deported 24 Eritreans who were seeking asylum, including adults and children. Upon return to Eritrea, these people and families face serious risks of arbitrary detention and torture by the ruling government.

In 2021, Libyan Coast Guards intercepted and returned 30,990 migrants and refugees to Libya. This was almost three times more people than in 2020. While in Morocco, police arrested more than 12,000 people attempting to leave through irregular means. This is potentially also linked to an agreement with the EU to prevent arrivals, as indicated in a leaked report by the European Commission in 2021. This report included proposals to strengthen cooperation with Libya and Morocco as part of the new EU pact on migration and asylum.

Additionally, Iraq repatriated 4,000 people from Europe since November 2021.This was after thousands reached the Belarus-Poland border seeking safety and asylum earlier in the year. Iraq’s repatriations were welcomed by the EU, and considered “good cooperation” in managing the crisis at their border.

Moving forward

The complexities of the migration experience in the MENA region, as well as the political relationships and dynamics that exist between nations in both Europe and MENA, creates an environment that criminalises migrant communities as a default approach, which adds to the vulnerabilities and risks faced by people on the move. Immigration detention is a core issue within this criminalisation approach, and IDC aims to continue strengthening its MENA Regional Programme in order to build civil society capacity, networks and advocacy initiatives to ensure that human rights and dignity are at the forefront of the migrant and refugee experience in MENA.

For more information about IDC’s MENA Regional Programme, please contact [email protected]

Written by Amera Markous MENA Regional Coordinator